No Wechat conversation is safe. Anytime. Anywhere. What Chinese are (not) talking about (4)

Wechat is almost universal. It is ubiquitous in China, and among the Chinese diaspora and their foreign friends and families. Its functionality for social media, news, and buying things makes it a better choice than any combination of applications available in the west. It is Twitter, Facebook, Googlemaps, Tinder and Apple Pay all rolled into one. And it is free.

Free does not mean without cost, of course, and in this case, the cost is the Chinese government being ready, willing, and able to monitor what you say, what you text, what you watch, what videos you post. In China and outside. If you think the long arm of Chinese government censorship doesn't reach into the US - well, you would be wrong.

SupChina cites a new report from Citizen Lab on WeChat censorship, surveillance, and filtering. Citizen Lab is based at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto. The lab studies government information controls, such as censorship surveillance and filtering, that affect the openness and security of the internet that pose threats to human rights. Citizen Lab seems to be an extraordinarily sophisticated (to me, anyway) information provider for anyone interested in international government monitoring of individual communications. Highly recommended. Read the wiki.

The Citizen Lab report is (Can't) Picture This2: An Analysis of Wechat's Realtime Image Filtering in Chats.

Two key findings on international scrutiny of chat images and texts -

WeChat implements realtime, automatic censorship of chat images based on text contained in images and on an image’s visual similarity to those on a blacklist

WeChat facilitates realtime filtering by maintaining a hash index populated by MD5 hashes of images sent by users of the chat platform

As the predominant form of personal communication in China, Wechat receives directives directly from the government as to what should be filtered.

Wechat Moments, Group Chat, and one-to-one communications are filtered differently. Not surprisingly, filtering is heaviest for political, government, and social resistance topics.

Sometimes, the filtering does seem a bit much. A pdf of a student resume, sent to me in May of this year from China, was received in early July. Three short videos of my son at swimming lessons, sent from China to Chicago, were blocked on July 19. One doubts that the swimming pool could be understood as a state secret, but you never know. For the government, better safe than sorry in censorship. Last year, I was talking about events in Xinjiang with government friends of mine. They had fairly high-ranking jobs in a city police department, and I know they had access to information before it was disseminated to the public. They knew nothing of events in Xinjiang. That could have been feigned ignorance; but other Chinese colleagues suggested that no, my friends really did not know anything. “Everything is fine in Xinjiang,” they told me.

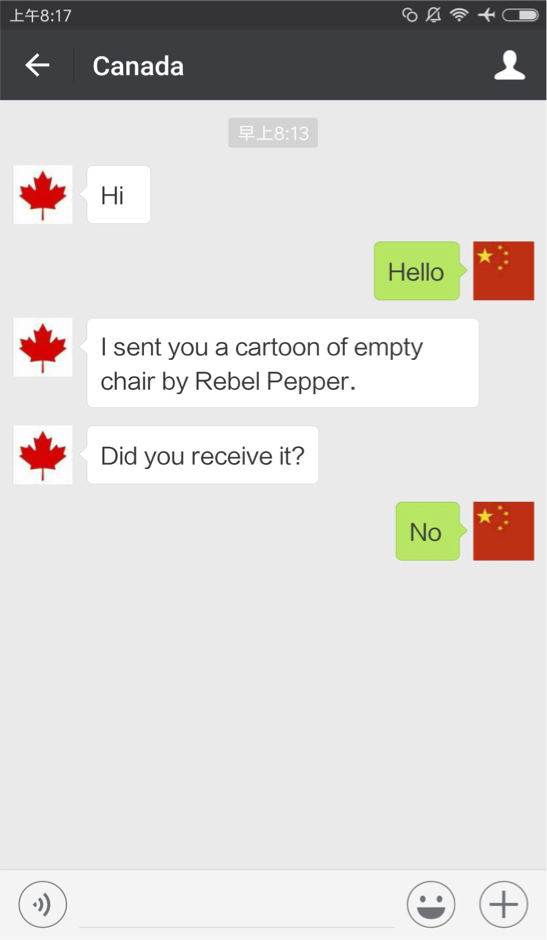

An example from the Citizen Lab report -

Figure 1: Left, a Canadian account sending an image memorializing Liu Xiaobo over 1-to-1 chat; right, the Chinese account does not receive it.

Stephen McDonnell, a BBC reporter in Beijing, describes being locked out of Wechat in China Social Media: WeChat and the Surveillance State. As he describes it, life becomes almost unbearable without access. He could not get a taxi, call friends or colleagues, contact sources for news stories, get airplane or train or movie tickets, make children’s school arrangements, or pay for almost anything. He was locked out while in Hong Kong covering the recent protests. He was allowed back in only when he provided his voice print and face print for WeChat. Now, as he says, no doubt he has joined some list of suspicious individuals in the hands of goodness knows which Chinese government agencies.

For anyone with morbid curiosity, here is a friendly guide in English on installing and using WeChat. Enjoy!