A bit long, but worth perusing …. use the red highlights to skip around …

An introduction

The US and China are two big countries and big countries with modern economies will necessarily have some similar problems. Middle class Chinese have concerns quite similar to those of middle class Americans.

We write all the time about differences between the US and China. Amid the anxiety and paranoia about ascendant China it might help to consider a few ways in which the US and China are similar. Just for some perspective. I’m not suggesting identical causation, only similarities in the way people experience the world. I ignore a lot of other similarities and all the differences in this short list. Some items might be interesting or fun or a bit of nourishment for you. No one should take this as an intimate analysis of those similarities that I do find. I am not making an argument here, just listing some elements of culture or economics that I find similar in China and the US.

Following below –

To start – physical size and location

Regional disparities

Decline of population and decline of population growth

Family structures

Isolated males

Families and children

Kid bullying

Housing crises

Households and debt

Government debt

The local fisc

Cities and infrastructure

Local government revenues and services

Inequality

People prosperity vs. place prosperity

Corruption

homelessness

peasants

health care

education

Health care and education and employment

Free speech and human rights

The race card

Drugs and treatment

Environmental change

International relations

The shameful history

Trust and benevolence

Civility

Democracy

Civil religion

Innovation and business

Politics

Aspirational intent

What is the government for?

To start – physical size and location on the planet

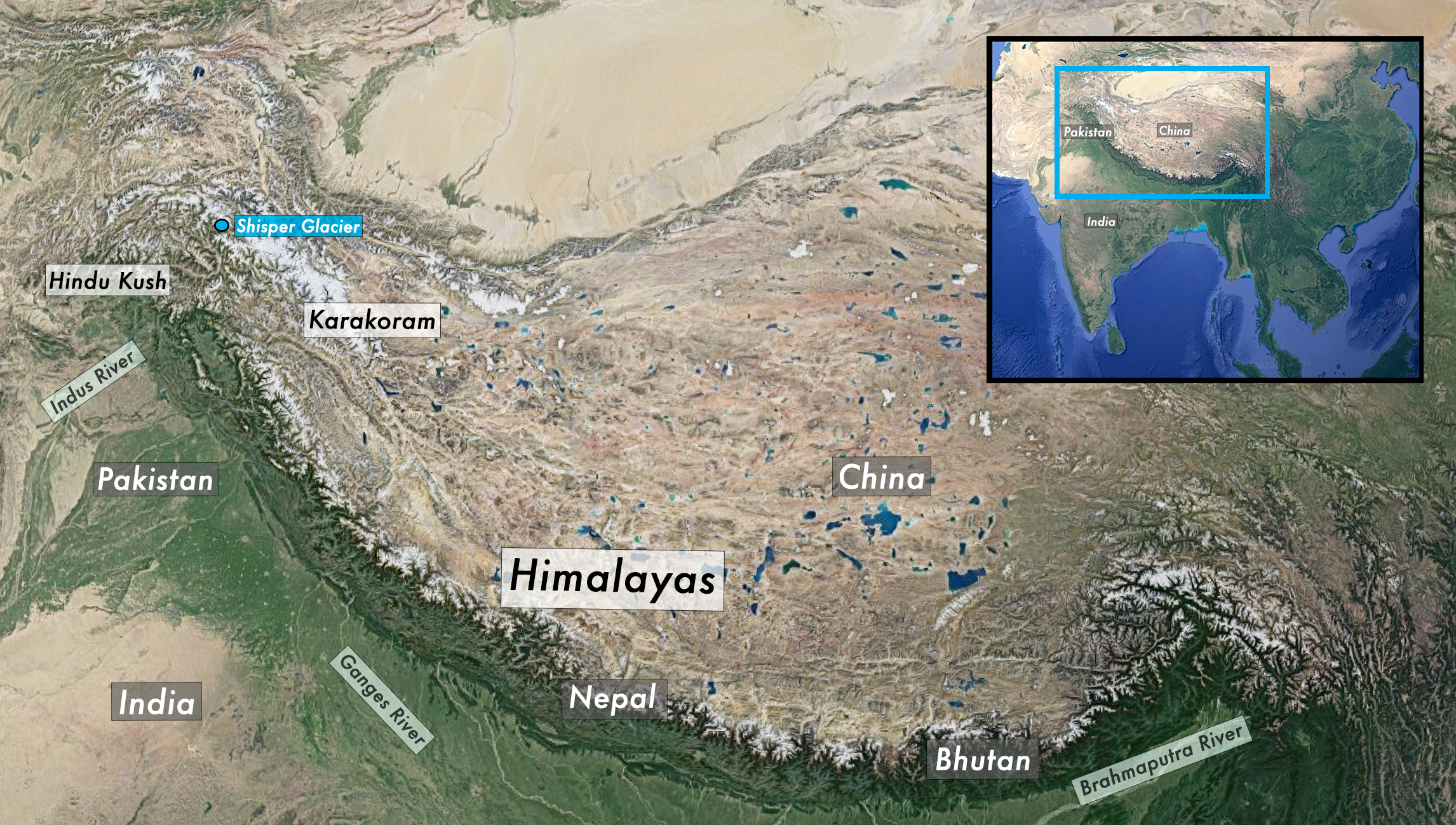

The US and China are remarkably alike in area and location in their hemisphere.

The furthest northern part of the contiguous 48 states is Northwest Angle Inlet in Lake of the Woods, Minnesota at 49 degrees north. The furthest south is Ka Lae, Hawaii at 19 degrees north.

For China, the furthest north is in Heilongjiang on the Russian border – Mohe County, Heilongjiang at 53 degrees north. The furthest south is Hainan Island, essentially the Chinese version of Hawaii, at 18 degrees north.

In other words, the two countries are nearly equally situated north-south on the planet. At the extremes China is further north by about 275 miles and further south by about 69 miles. The area of the US including Alaska is about 9.8 million square kilometers. The area of China including Tibet and Xinjiang is about 9.6 million square kilometers. In other words, they have nearly the same area.

For both countries most of the population and most of the economic and cultural and intellectual capital is near the east coast, with some central outposts in Chicago and San Antonio and Chengdu and Chongqing. To the west are empty plains and mountains. When we write about the countries, we mostly write about the east coast, New York and Washington and Boston, and Shanghai and Beijing and Tianjin. Sometimes about Florida and Texas and Hong Kong and Shenzhen. And ok – maybe its not fair to pair Los Angeles and Seattle with Llasha and Urumqi. Whatever. Population is more bifurcated in the US – there is a west coast. But New York and Shanghai – pretty good comparison in terms of domestic and international importance.

There are about 2900 county-level divisions in China (like everything else in China, the definitions are fuza – complicated). There are about 3100 counties in the US. In both the US and China, counties are sub-provincial or sub-state jurisdictions.

There are cowboys in the west, with cowboy hats and horses and cattle. In Shenyang, in Liaoning, the corn grows more than ten feet high and they use John Deere equipment to harvest. There is snow in Dalian and the rest of the northeast and it looks as pretty as it does in New York or Chicago and on the mountains in Maine and Vermont. I have a photo from the second floor of a favorite Starbucks in Hangzhou, looking down on the side street with a FedEx delivery truck double parked next to the Fords and BMWs. Indistinguishable from a scene in any US city. The red hexagon stop sign said 停 ting Stop.

Regional disparities

In such large countries, one would expect to find large regional differences in economic structures, health care, education, food and customs. One could write volumes. The differences in dialects and customs and food preparation are well known, in the US and China. One source found 24 varieties of American English. American can generally understand each other, though.

There are probably hundreds of mutually unintelligible varieties of Chinese. Major divisions are shown below.

These dialects really can be mutually unintelligible.

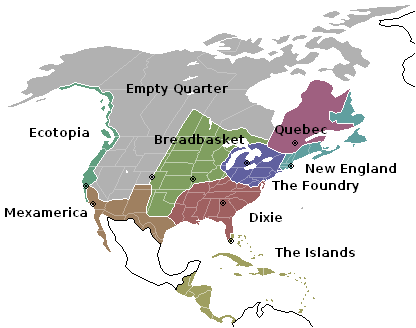

Geographically and just for fun, a comparison – Joel Garreau’s The Nine Nations of North America and long time China researcher Patrick Chovanec’s The nine nations of China (Atlantic, 2009).

Garreau –

And Chovanec –

Source: Patrick Chovanec, The Nine Nations of China. Atlantic Magazine, November 2009, at

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/11/the-nine-nations-of-china/307769/

The nine nations of China were initially suggested by G. William Skinner in his 1977 Regional Urbanization in Nineteenth-Century China in The City in Late Imperial China. He suggested that the nations were somewhat autonomous. Not much trade crossed borders, and there is still some truth in that.

Some of the area descriptions do correspond well – the Foundry in the US is matched to the Rust Belt of dongbei, the northeast, in China. Garreau’s Empty Quarter would match to the Chinese Frontier. Again, this is just for fun. Let’s not get too exercised over the comparisons. As with Garreau’s description of North America, there is a grain of truth in the nine nations of China.

Decline of population and decline of population growth

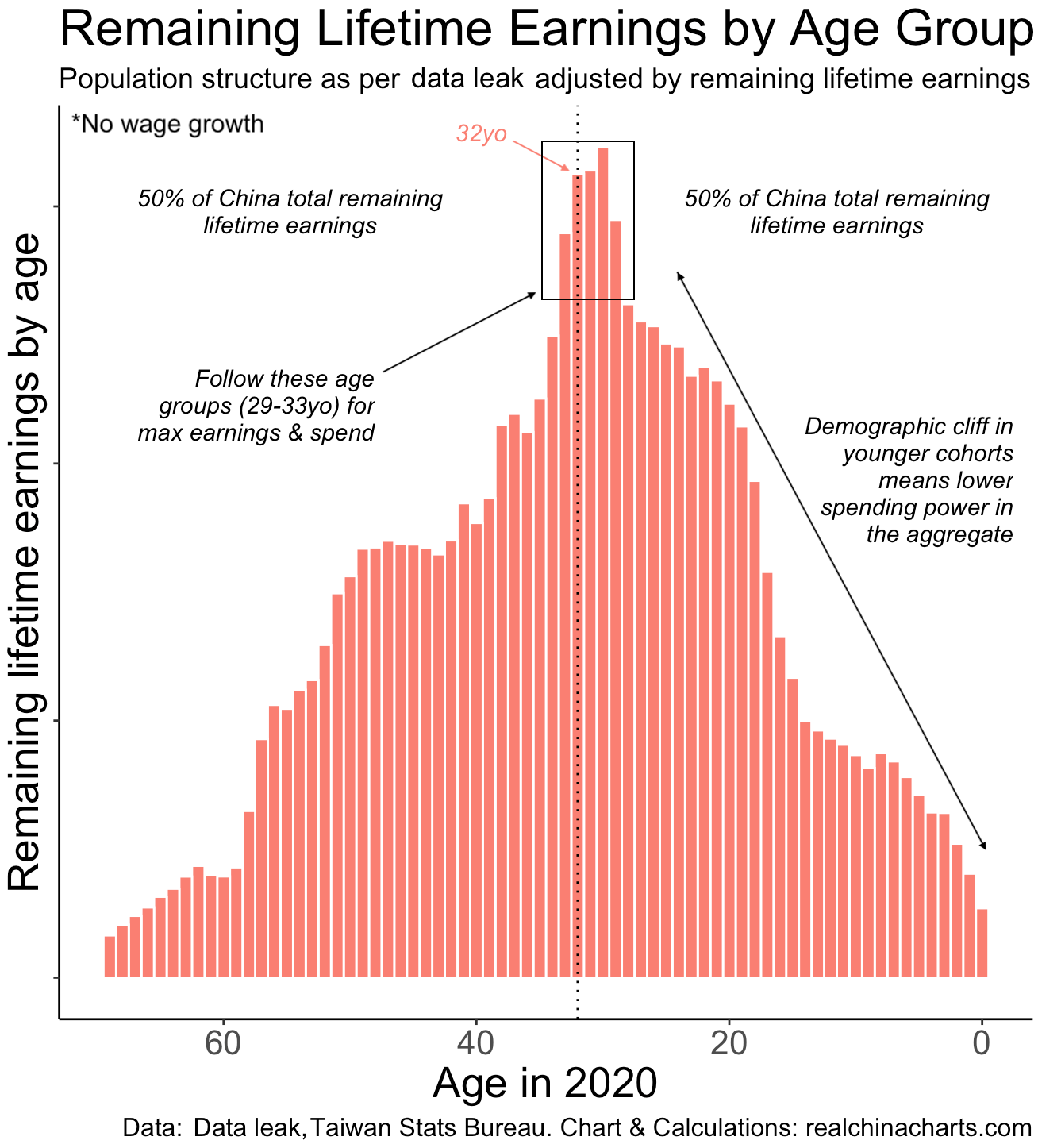

On to some more useful comparisons. All of our lives China has been the world’s biggest country by population. That is no longer the case. India has now surpassed China. The population of China has begun to fall because of the one-child policy, a cultural preference for male babies, and abortion of first-born females. There are now about 35 million more men than women in China, most of them born since 1980. These are men who most likely will not find wives or be able to produce an heir. Chinese government sources project the total population to fall by 50% by the end of the century, meaning millions of fewer people each year. The working age population is currently falling by about 5 to 6 million per year. There is no real immigration.

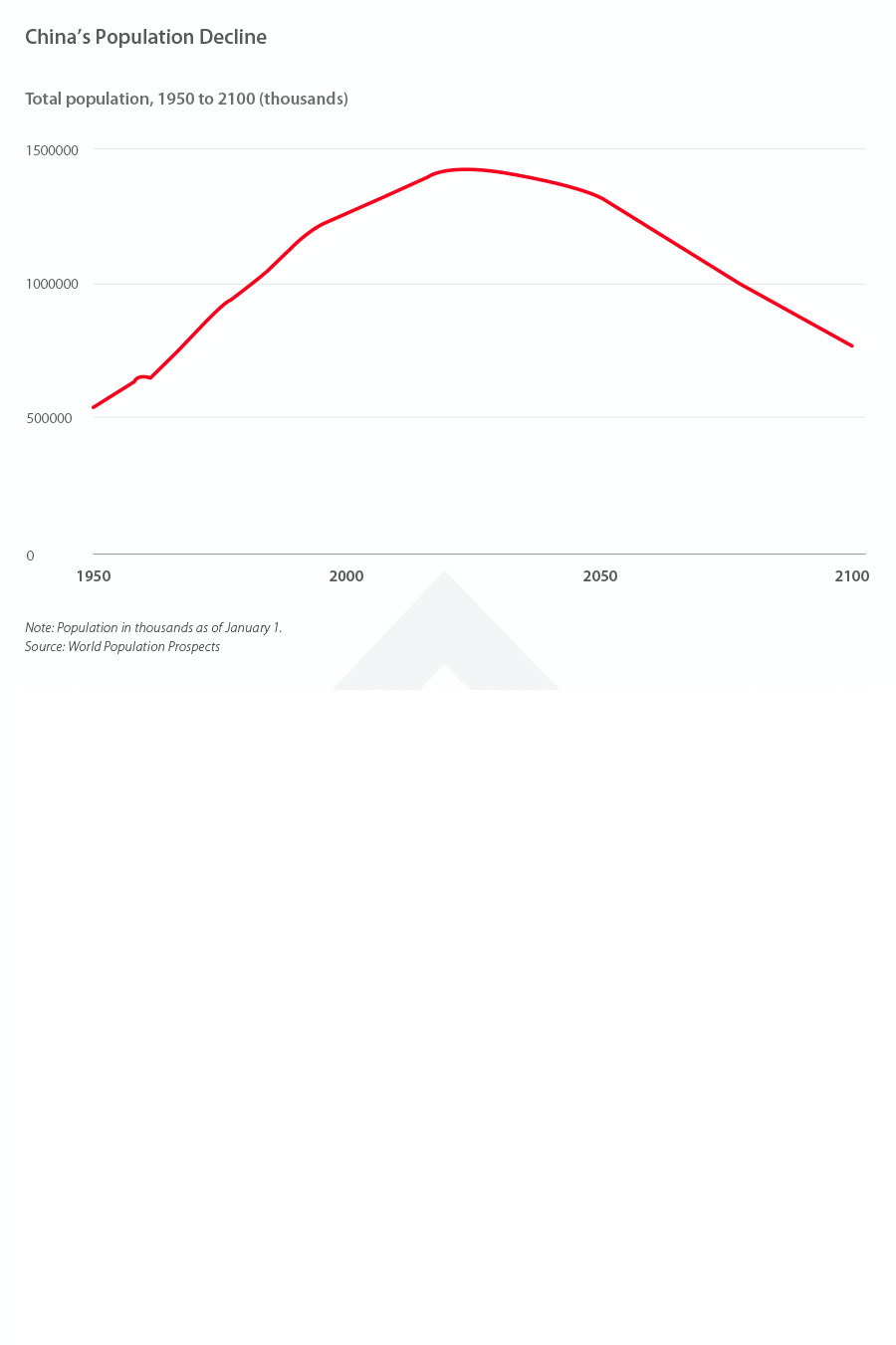

The graph below is surprising. The forecast is to lose 700,000,000 people in about 80 years. Fertility right now is about 1.09 children born per female, far below replacement rate.

The similarity with the US is in the falling population of its long term residents. US population would be falling if not for immigration. It is estimated that about 80% of US population increase in the next thirty years will be due to immigration. The Congressional Budget Office projects US population increases from 336 million people in 2023 to 373 million people in 2053. Immigration will account for nearly all population growth beginning about 2042.

U.S. population is growing slowly, not falling as in China. But slowdown in population growth is becoming an issue in the US as well. New Census Bureau data released at the end of December shows that the population of the U.S. grew just 0.4 percent in 2022, which is better than in 2021 but worse than every other year of the past hundred years. For a population to stay the same size, the average woman needs to have about 2.1 kids and the US is nowhere near that now. While the U.S. fertility rate was 3.6 in 1960, it fell below replacement level in 1972 and remained there for about 35 years. Then it started to fall again and is currently around 1.6. US population growth depends on immigration, which in the last few years has been curtailed by government policy – America’s population could use a boom (Jeff Wise, Intelligencer, January 3, 2023).

Fewer births don’t just lead to a smaller population but to an older one, since the younger cohorts aren’t large enough to balance the older ones. Since 2000, the median age in the U.S. has grown by 3.4 years to 38.8. By 2034, the number of Americans over 65 will exceed that of children under 18. The median age in China now is 39. (In 1978, China’s median age was 21.5 years). China will keep on surpassing the US in median age for the foreseeable future. By 2100 the median age will be about 57.

Soon ever-fewer working-age Americans will be supporting a steadily growing population of retirees. This will soon be very evident in China as well. Circa 2010, I recall thinking that everyone walking around the downtown of cities in China looked young. (That was a reasonable conclusion. Older people were back in the village or at home cooking for the working parents. And you know the characterization – Chinese always look about age 26 until they get to be about 55, then they look 80). Walking around downtown Chicago, everyone seemed much older.

And there are other less tangible effects of an aging population, too. “A younger population makes us more vital, more innovative,” says William H. Frey, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. The Congressional Budget Office has population forecasts to 2053. Starting about now, the US and China will have a lot of old people who need more and better health care and social services.

Polls show that many Americans want more children than they are having. Also true in China. But the slow-growing incomes and a shortage of good child care options and the expense of raising children have led some people to decide that they cannot afford to have as many children as they would like. The decline in the birthrate, in other words, is partly a reflection of the failure of society – American and Chinese – to support families.

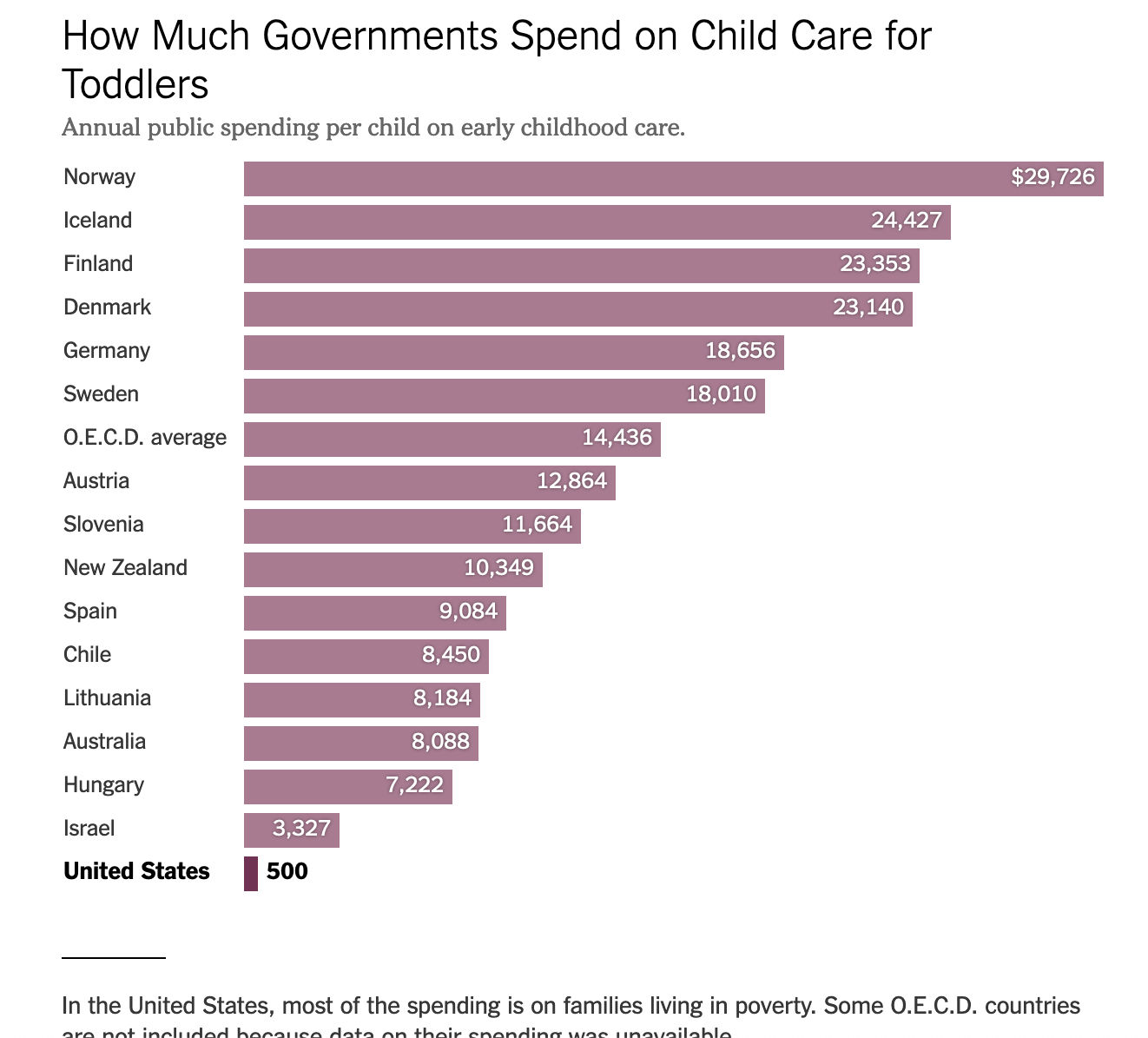

Failure to support families, particularly kids, is an American tragedy. No other developed country does as little for its future generations in terms of parental leave, sick time, health care, and day care.

China provides child care via cultural means for middle class parents. It is customary for grandparents, usually the mother’s parents, to move in with the kids to take care while the parents are at work. This usually involves all cooking and cleaning as well. Middle class parents who cannot avail themselves of a grandparent can hire an “auntie” to do caretaking and perhaps some cleaning. Aunties may be live-in or not. But there are the usual qualms about hiring someone to take care when no one is around to monitor. True in China, true in US.

An upside for both countries is that less immigration to the US and aging population in China will create opportunities for current lower-paid workers. And there are some advantages to slower population growth. A lower birthrate can expand the economic opportunities for women, especially because the U.S. has relatively flimsy child care programs. Historically, birthrates have declined as societies become more educated and wealthier. The NYT has more on the upside and downside of slow population growth. Anyone remember ZPG?

There are some similarities in the reasons for decline in fertility – more education for women, more women with modern and high paying jobs, better health care for pregnant women and newborns. Financially independent women have fewer babies in both countries. The demographic changes permit women to be far more selective in choosing a mate. In the US sixty-three per cent of men aged 18-29 are single; 34% of women in that age group are single. In China, about 55% of men are single; about 39% of women. It is a real problem for millions of men in the US, and in China particularly, where there are about 35 million men who will be unable to marry. A somewhat funny recognition of this serious problem is rendered in the No House, No Car song, popular in China in 2012 –https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G_G4S8Kws8o

One counter factual – Since the elimination of the one-child policy there are confirmed second children born in China now, although far fewer than the government wants. According to the Hangzhou Municipal Health Commission birthrates for second children have declined every year in the city since 2017; but local media reports that in 2022, the number of second-born children was 19,200, accounting for 36% of all children born there.

Family structures

Decline of the nuclear family is now an old American story. Single person households now make up 27% of all American households. Gay couples may adopt kids in all fifty states.

There are similar trends in China, although without the gay adoption. In China now, 25% of all households consist of a single person. In East Asia’s New Family Portrait we see that a modern economy and feminist ideas have made women far more selective in choosing a mate, less inclined to have children, and find ways to make a life without a commitment to another person at all. Fertility rates in China (as in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan) are substantially below replacement. The Communist Party has censored feminist and LGBT groups and arrested some of their most prominent activists.

These trends resemble those in the West from the 1970s onwards, but with different causes. It is said that changes are driven by anxieties, social problems and social conflicts, not the triumph of the individual. Pressures to buy an apartment, marry, have a child, make money, and honor the ancestors are really too much for lots of modern middle class Chinese. In both the US and China home prices are unaffordable for many and debt constrains plans to marry or have children. In the US, debt may be student debt; in China it is almost certainly mortgage debt.

In China 8.3% of households in 2000 had just one person; by 2020, the ratio had increased to 25.4%. In the US there were 37.9 million one-person households, 29% of all U.S. households in 2022. Just 18% of US households are ‘nuclear families’ with a married couple and children, down from 40% since 1970s and the lowest since 1959. Chinese data shows about 60% nuclear families.

Isolated males

Isolated, lonely males are a social problem in both countries. Involuntary celibates – incels – in the US define themselves as unable to find a romantic or sexual partner despite their desire for one. Incels are often characterized by resentment, misogyny, misanthropy, self-pity and self-loathing, racism, a sense of entitlement to sex, and the endorsement of violence against women and sexually active people. Some mass murders are attributed to incels. Causes of involuntary celibacy are sometimes attributed to lack of income or wealth, physical unattractiveness, poor social skills and lack of opportunities. Incels and related movements have been defined as terrorist threats. A good discussion is at Single and Lonely: American Young Men in Crisis.

Involuntary celibates in China are a result of the one-child policy and cultural preferences for male children. The one-child policy began about 1978 and by now has produced about 35,000,000 excess males. These men generally live in small towns or rural areas, have only a peasant hukou, do not have attractive jobs or prospects. In popular parlance, they do not have the house, car, or significant bank account that would make them attractive to now more selective urban women. These men will most likely remain single. Inability to produce heirs is culturally shamed, although modernization mitigates pressure to some extent. There is no organized movement of isolated lonely males in China – as they are no organized movements of any kind – and CCP does not seem to consider them a terrorist theat. But young migrant workers are thought to be responsible for the great majority of urban crime, particularly violent crime. It is reported that migrants account for over 50% of all criminal cases in the major receiving cities for migrants, with some cities reporting such figures at up to 80%.

In China, for hundreds of years women were the product of an unfortunate pregnancy. Women only began to get credit for holding up half the sky under Mao, and even then, baby girls were aborted at astounding rates (Causes and Implications of the Recent Increase in the Reported Sex Ratio at Birth in China, Zheng Yi et.al., Population and Development Review, 19:2 June 1993).

Times are different now. And heterosexual women are more choosey now they are considered a prize. This partly serious video from 2012 No house, No car pointedly explains.

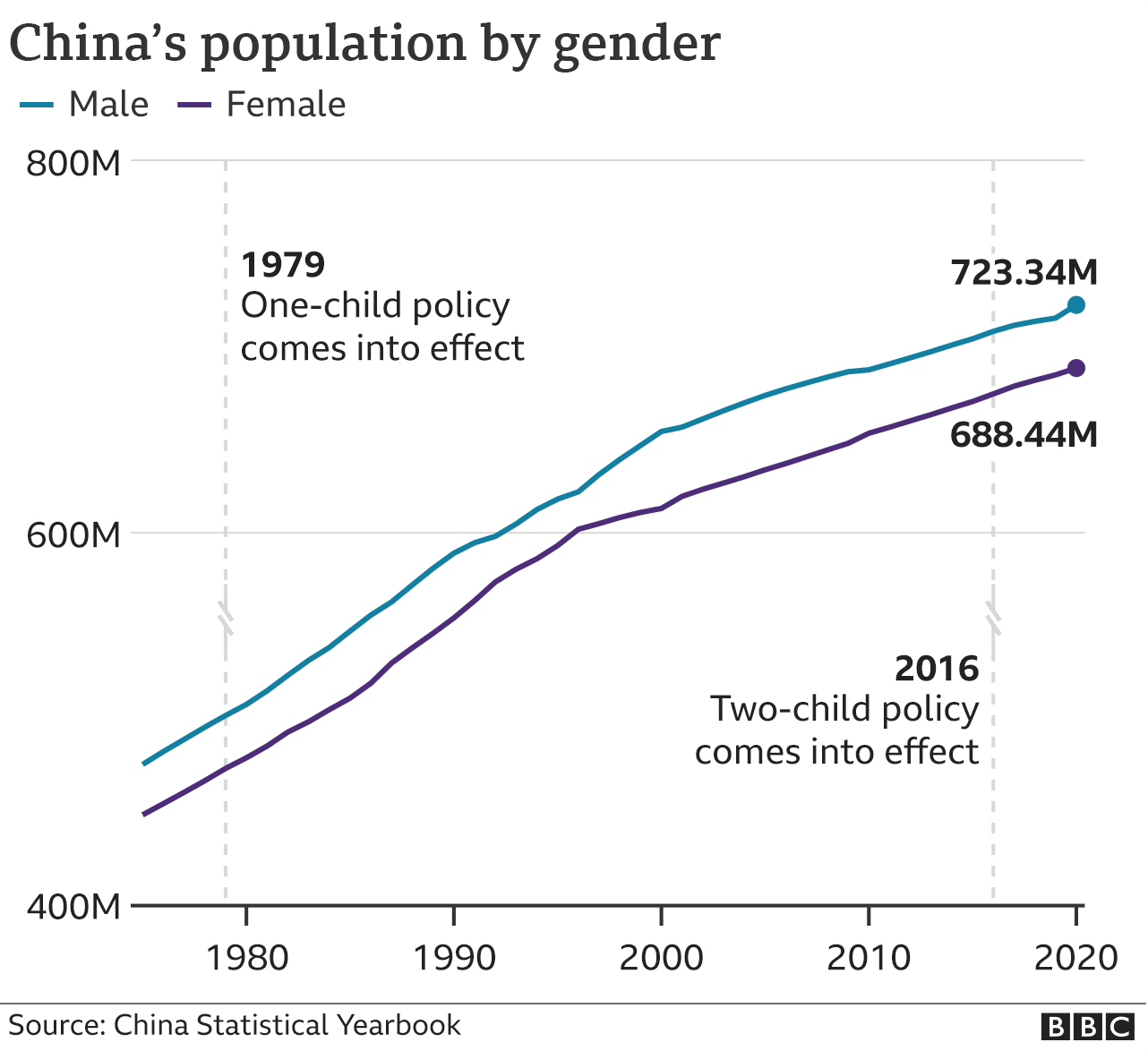

Online gaming and porn distract some young men. The sex ratio in China is particularly bad, a result of the one-child policy and strong preference for male offspring. The military will absorb some of the excess males; but the excess males going into the military will be less qualified than the average American high school graduate who joins. Below you can see the 35,000,000 extra males.

Source: China Statistical Yearbook

Source: China Statistical Yearbook

More on the sex-ratio imbalance is here. Some Chinese women, as picky as they are, have to finally resort to marrying barbarians – foreigners.

Families and Children

Young adults in both countries question the wisdom of becoming a parent. There just isn’t much help offered, though both governments are making attempts. From Why is Raising a Child in the United States So Hard? – The infrastructure and family plan that President Biden proposed and that’s now being negotiated in Congress is an attempt to shrink the gap through four key policies: a federal paid family and medical leave program, an extension of the child tax credit (in the form of a monthly payment) that debuted this year, subsidized day care, and universal pre-K.

It is hard in China too. China is not even on the following chart. The US seems on the chart only as a courtesy.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/06/upshot/child-care-biden.html

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/06/upshot/child-care-biden.html

In both countries the extended family traditionally was available to take care of kids. That is still true to some extent in China, less so in the US. In both, far too many kids grow up with inadequate attention, health care, and education, thereby preparing them poorly to function in a modern economy.

Kid bullying

Bullying and cyberbullying are issues in both countries. We talk about the deleterious effects of cyber bullying on teens, particularly young teen girls. This is an issue in China as well – China ramps up fight against cyberbullying in wake of deaths.

I thought this online post below was a nice comment on the question about bullying in China.

How prevalent is bullying in Chinese schools? What are some typical examples?

Yexi Wang https://www.quora.com/profile/Yexi-Wang

Studied at Hangzhou No. 2 High School (Graduated 2021)

Bullying, how common is it in Chinese schools? In my entire six years of elementary, no. We were hyperactive, cute and sometimes annoying normal kids without the nature of bullying anyone.

Things started to change a bit. I went to an average (some times above) public school. My grade had 10 classes, each consists of about 35 students so the total number was about 330. Public middles schools in my city work like this: A middle school absorb fresh new elementary graduates from usually 2 to 4 different elementary schools. I can proudly say that kids from my elementary were very good natured and never had the reputation of being bullies.

But that doesn’t mean all the kids were nice. There was a girl, a rich girl with a bunch of allowance yet not really cared by her parents, I heard her parents divorced and I assume that is reason why she has a bitter temper towards people. She was sometimes secretly called “the non-virgin”, everyone is my grade knows it. She was somewhat beautiful, but I don’t want to see her ever again. Teens always use the word “social” to describe them. So I’m leaving an impression here.

I was confronted by her and her little vicious group in front of the girls’ restroom once. She and her “friends” directly said things like “OMG she is so fat like a pig” in my face but I ignored them. She was also pretty good at cyberbullying. She found me on a chatting app and dragged me into a group and she wrote “You better watch your mouth otherwise I will beat you until you have an abortion” “You can eat poop anywhere but you can’t shit with you fxxking mouth” blah blah blah. It actually freaked me out that night.

Things went better for me though, my mom told me not to be scared. She even told me how to defense myself in case things get out of control. I told my teachers later, and they say they will protect me as well. My friends supported me by walking me home everyday for about two weeks. I was relieved.

The reason why she was mad at me, to an extent, I should say I brought it on myself. I was joking with my friend saying “wow the girl next to her (the bully) really looked like her servant” (which is the truth since the bully buy things for her friends) and someone heard it. I knew I was dead wrong and I sincerely apologized several times, I knew I was too judgmental and it’s really not my business. But she wouldn’t take it. Well.

I was sure she was a bully because that’s what they often do to anyone who is against her wishes. I heard it from my friends. Anyway there was only this girl though, I don’t think there is anyone else like her.

Please be aware that I’m living in the central part of Hangzhou, the capital city of Zhejiang province, where is much much more developed than rural areas. Bullying seems to be much more serious in rural areas because the parents might not always be with their children. The victims weren’t protected, no one ever taught them how to defense themselves, the teachers didn’t care, the bullies’ never know that he or she was wrong. I once saw a video shoot in a village, a girl was kneeling before four peers and she got slapped over and over. Just imagine the shocking scene! She didn’t run away or fight back, she was just kneeling and crying begging for forgiveness while the four girls kicked and slapped her nonstop. Their parents probably left the village to work in the cities to make money and left their children alone. So sad.

Sorry if I digress, it just took me a while to recall these memories.

Thanks to the A2A.

Yexi Wang

Housing crises

Housing markets in the US and China are quite different, but with respect to housing crises they have some similarities.

Housing prices rise and fall in the US and buyers generally understand that. The US had its own severe crisis in 2007-2010. Chinese have never seen a housing crisis before, but they are going through one now that will not abate for some years.

The circumstances are quite different, as is the resolution, but in the end home buyers in both countries end up paying for overreach and illegal behavior by others. In both the US and China irresponsible lending is at base the cause of the crisis. In the US, lenders made NINJA loans – no income, no job or assets – and there were plenty of violations of local and state laws.

In China, individual apartment purchase loans were made two or three years before completion of the project, and buyers began paying at the signing of the mortgage, two or three years before completion. Money from the bank went to the developer. The funds to the developer were supposed to be segregated and used for completion, but they weren’t. Funds were used to buy land for the next project. It was a variation on a Ponzi scheme. Eventually the game stopped.

In both the US and China the government bailed out lenders – and in China, developers – and left individual buyers out in the cold.

Households and debt

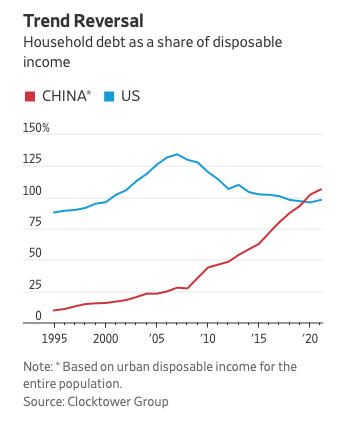

In the US household debt got far out of balance before the 2008-10 financial crisis. The same thing can be said of Chinese residential property values now and in the last decade.

Chinese household balance sheets are in poor shape, and about 80% of Chinese household wealth is in real estate. “Household leverage ratio” means household debt from all sources as a per cent of national GDP. The IMF uses 65% as a red line warning about financial risks. From Caixin, referencing 2023 data – Charts of the Day: China’s Household, Overall Debt-to-GDP Ratios Rise to a Record – Caixin Global

The household leverage ratio stood at 63.5% at the end of June, the second straight quarterly increase, according to a report by the National Institution for Finance and Development (NIFD). Although that’s the highest in available data going back to the end of 1992, it was just 0.2 percentage points higher than at the end of the first quarter when it jumped 1.4 percentage points from the end of last year to 63.3% as the economy reopened after three years of Covid-19 controls.

The report attributed the sluggish growth to slumping property sales, with outstanding mortgage lending falling 0.1% on a year-on-year basis at the end of June, the report estimated based on data from the People’s Bank of China (PBOC)…

Even so, households were still borrowing. At the end of June, outstanding consumer loans rose 11.1% year-on-year and individual business loans jumped 19.5%, the report estimated.

At the same time, households cut back on spending and beefed up their savings in the second quarter as concerns about future income growth mounted, according to the NIFD report. Outstanding household savings surged by 10% to 133.1 trillion yuan ($19 trillion) in the first half and are projected to still rise at a relatively fast pace in the second half, the authors estimated…

In the following chart one can see the American household debt crisis coming to China about fifteen years later.

Source: https://twitter.com/greg_ip/status/1667940913631379458

The government has been telling people for a decade or more, “houses are for living in, not for speculating” – all the while encouraging people to buy, buy, buy. Sounds a lot like the US circa 2007. In summer 2023 prices are now falling in cities across China, 5% to 10% in most cases and reportedly up to 25% in some parts of Hangzhou, near where Alibaba has its offices. (That is a newly developed area with very expensive apartments and homes. It is also where the CCP Zhejiang Province School of Administration (Party School) is located). Corporate and household debt is at about 250% of GDP, a worrying figure. The US and EU, post 2008-2010 crisis, are now at about 150% of GDP.

Government debt

We worry off and on about US government debt. The total is now about $32 trillion. That is a lot of money, even by the standards of Everett Dirksen, the popular Illinois senator in the 1960s – “… a billion here, a billion there, and soon you’re talking about real money.” States and local governments are required by law to have balanced budgets, so state or local debt may be a problem but it does not affect the government in Washington.

Central government spending as a share of GDP in the US is about 25%; in China the share is about 32%, although the reported China numbers differ substantially across reporters, based on differences in definition. The US runs substantial deficits each year. China runs a small deficit each year. At a gross level of analysis, the US spends on defense and debt payments and social services, while China spends on defense (now rising quickly) and much less on social services and debt. The central government share in China does not include substantial provincial and local government debt, which are the source of most worry right now.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. told us that “taxes are the price we pay for civilization.” It appears that Americans are opting for less and less civilization and we are reaping the benefits of what we don’t pay for – terrible gun violence, terrible schools, fear on the streets, inadequate funding for schools, health care, and social services. With that, we still accrue annual government deficits. At one time our taxes provided good government support for innovation – the Covid vaccine and NASA and the internet and semiconductors and the intercontinental railroad. But we fear doing that sort of spending now. The economic partnership model that worked since Hamilton is broken.

China has very serious debt problems at the provincial and local levels and in households. The household debt crisis is due mostly to required payments to developers long before a unit is delivered, with buyers still on the hook for a mortgage on an apartment they cannot occupy. Millions of those apartments now cannot be delivered without central government rescue.

The household debt problems create problems for local governments too. In recent years a substantial share of local government revenues came from selling land use rights to developers. In some cities the real estate revenue share approached 50%. Now developers don’t want to, or more correctly, are legally unable to, buy more land.

The provincial and local government debt problems are essentially due to vast overspending on infrastructure and real estate. Most of the money for projects is borrowed using a form of public-private partnerships (local government financing vehicles, or LGFV) to get around limitations on local government borrowing. Many of the projects built this way have no possibility of ever repaying the loans taken out to build them – hence the debt problems. More than 80% of local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs, do not have enough operating cash to cover interest payments on their debt, according to estimates by UBS. In China the economic partnership model that worked since about 1990 is broken.

“Bad banks” were created during the financial crisis of 1999 to take over bad loans and see what could be salvaged, while getting the ”good banks” off the hook. The top four bad banks –

China Cinda Asset Management Co. Ltd., China Huarong Asset Management Co. Ltd., China Great Wall Asset Management Co. Ltd. and China Orient Asset Management Co. Ltd. — had total debt-to-equity ratios range from 400% to 1,200% at the end of June, 2023. There are provincial and municipal bank banks as well.

These banks will have a significant role in resolution of the current financial crises. While the bad banks may have debt that precludes raising more money from investors, the Chinese government will be available, as earnestly as they deny that potential right now. For evidence, I present the ability of Cinda to go public in 2013 while holding trillions of RMB in bad debt or bad projects. Going public was only possible because – in a little reported development – the Central Ministry of Finance began bailing out Cinda in 2010. After 2010 – The Ministry of Finance bailed out Huarong in 2021. More on the asset management companies (AMC) is available here.

There are some similarities in the Chinese resolution from 1999 to the actions by the US Federal Reserve in 2007-2010. Banks were flooded with liquidity if there seemed a chance of remaining afloat. Hundreds of banks were closed by the Federal Reserve and assets sold.

… governments and central banks, including the Federal Reserve, … provided then-unprecedented trillions of dollars in bailouts and stimulus, including expansive fiscal policy and monetary policy … and provide banks with enough funds to allow customers to make withdrawals….

The similarity makes sense. There are only so many ways for governments to bail out banks from their bad decision-making. In both China and the US, borrowers were left with little or nothing. Government regulation failed in both countries. Only in the US did the central bank chairman – Alan Greenspan – express surprise that the banking system failed to self-regulate.

The central government debt is about 80% of GDP, which is a nominal figure. But when provincial and local debt is added in, the picture gets darker, to about 250% of GDP. The US and EU are at about the same ratio.

The local fisc

It is no secret among policy analysts that most of the Republican leaning states are heavily dependent on the federal government for annual support. In recent years 7 of the 10 states most dependent on the federal government were Republican-voting, with the average red state receiving back $1.05 per dollar of taxes contributed. Texas and Florida are the notable exceptions. One wonders if Texas and Florida will seek federal help in dealing with climate change and rising sea levels.

China is in a similar spot.

Under the present tax-sharing system, provincial and municipal governments are responsible for most social spending, without the ability to raise sufficient revenues. Data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics show that land sales dropped by 53 percent (in terms of area). According to China’s latest budget report, declining land sales led to a 20.6 percent drop in revenue within the government fund budget. As in the US, municipal employees are being underpaid and jobs are going unfilled because of local budget problems. This is new in China, old in the US.

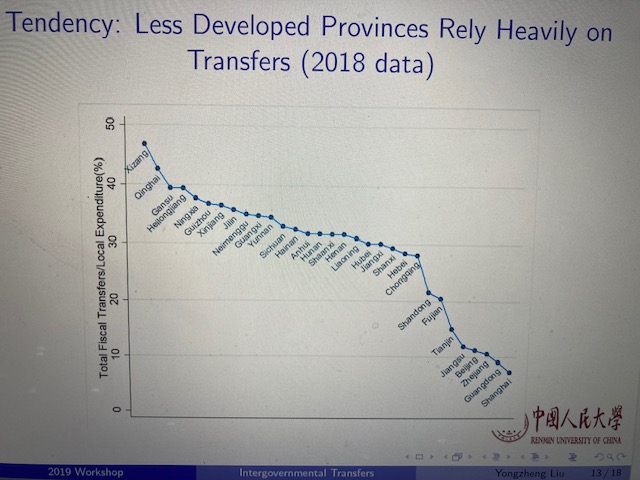

The following chart does not indicate which provinces are net recipients of money from the central government, but only a few provinces and the province-level cities like Beijing and Shanghai are net “profitable” in the eyes of the central government. Most provinces, like most red states in the US, are net recipients of tax money from the center.

In China disparities are most obvious when comparing the east coast provinces to the rest. From Caixin – China’s East-West economic gap refuses to narrow –

Despite a push for more balanced development, the economic gap between China’s better-off eastern coastal regions and its less-developed western inland regions remains wide, according to the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC).

The western region, including 12 provinces and autonomous regions, accounted for 21.4% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022, up from 19.6% in 2012, NDRC Vice Chairman Zhao Chenxin reported to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. The ratio of GDP per capita in the eastern regions to that in the western regions declined to 1.64 in 2022 from 1.87 in 2012.

Source: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Day%202%20Session%205_Yongzheng%20Liu_Intergovernmental%20Fiscal%20Transfers%20in%20China.pdf

Western China’s Gansu province had the lowest GDP per capita in 2022 at 45,000 yuan ($6,206), less than a quarter that of Beijing, which had the highest.

Both countries have concerns about debt payments as part of the general national budget. The US share of expenditures toward debt payments is about 8% and is expected to rise fairly rapidly. The Chinese share is about 4% but that does not include provincial and local government debt, which is not balanced each year, is expected to rise dramatically, and will require a central government cover one way or another. A more likely number is about 7% for all Chinese government debt payments.

Cities and infrastructure

Cities in the US are generally in poor physical condition. Subways go without needed funds, transportation connections are … pitiful, schools are starved, water is sometimes unsafe and healthcare, while absurdly expensive, is of spotty quality in poor areas, urban and rural. Meanwhile, many suburbs are basking in the taxes they derive from people whose employment is in or tied to the city. If there are municipal debt problems or high taxes, these are conceived as only city problems.

China has prioritized city construction and city development, as we see with the airports and subways and expressways and development zones. Almost nothing you see in China is more than forty years old – probably less than twenty. Central cities in China look new, and they are.

Critical to local government fiscal health is that cities encompass an entire labor shed, so the central city and its suburbs are one fiscal entity at the most fundamental level. The example I know best is the city of Hangzhou, which is about 16,000 square kilometers (about 6,200 square miles). In comparison with Chicago, it is as if Chicago encompassed all the area from Waukegan to Elgin to Aurora to Joliet to Gary. But fiscal health is about more than taxing and spending. It is also about investment, and that has been the flaw in Chinese local government fisc.

Cities in China are understood as the engines of economic growth. And from 2008, the central government stimulus money has gone to build, build, build anything and everything. Most of that money was leveraged three to five times on short term loans. Many of the projects had no hope of repaying the money used to build them. It was the Chinese version of NINJA loans, scaled way up.

But now the demands for debt repayment (mostly for infrastructure and real estate) are forcing cuts that look like American city cuts to budgets. From a New York Times article on Shangqiu in Henan Province – China’s Cities are Buried in Debt, but They Keep Shoveling It On –

Shangqiu is one of more than 20 towns and cities in China where bus services were shut down or put in peril because local governments had failed to provide the necessary operating funds. Wuhan and other cities cut health insurance. Still others slashed the pay of government workers. Many local governments in Hebei Province, which borders Beijing, failed to pay heating subsidies for natural gas during the winter, leaving residents to shiver during a record-setting cold wave.

But Shangqiu is not planning to spend the money on public services. On the contrary, the city plans to cut spending on education, health care, employment protection, transportation and many other public services, according to budget documents on its website.

Some Chinese cities are cutting medical benefits for seniors. As in the US, seniors are a potent force for influencing government policy. Protests, some violent, have taken place in 2023 as local governments began cutting their contribution to seniors’ personal insurance account for medicines and outpatient costs. More at China’s Cities are Cutting Health Insurance, and People are Angry and Making Sense of China’s Government Budget.

In the US, state and local governments are forced to balance their budgets each year. There certainly are units of government that get into financial trouble, usually – as in China – from excessive borrowing, but the US government takes a hands off approach, as does the central government in China. The US government, echoing state and suburban governments, fails to support cities starved of revenue by ancient and arbitrary municipal boundaries.

The Chinese government is making a bold show of denying that it has any responsibility for local government debt – “you borrowed it, you own it.” But that denies the central-local fiscal relations that required local governments to get into debt in the first place – local responsibility for nearly all social services with hamstrung ability to raise money, no ability to issue bonds, and local rulers bent on building as much as they could as fast as they could. The central government has already structured deals to provide relief for a couple of LGFV, and is leaning on the state-owned banks to make local debts disappear. The government will be able to kick some cans down the road for a few more years, but even the “bad banks” created to take over the bad debts of SOE are themselves requiring bailouts. A lot of cans will prove too big to kick. The need to service or cancel bad debts will hamper the central and local governments in the next decade. A good summary with maps is at Macropolo.

Deleveraging happened to Scandinavia and Japan in the 1990s, and in the US after 2007. It is coming to China at a time when spending on people rather than things is a looming crisis.

All debt – households, government and business – has reached about 282 per cent of annual GDP. The US figure is 257 per cent and the average for developed countries is 256 per cent.

Deleveraging is coming to households as well, as it did in the US. People are paying off mortgages if they can and not buying that second or third or tenth apartment. Everyone’s fiscal future is more in doubt now than any time in the last forty years and Chinese are not used to that.

Local government revenues and services

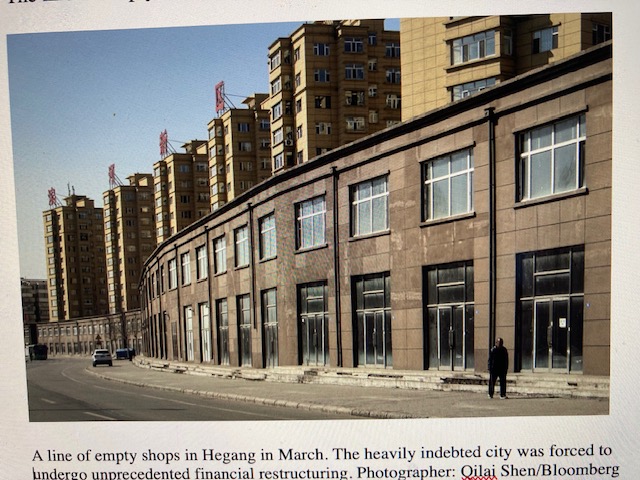

Local governments face budget cuts and reductions in services and inadequate spending on health care and pensions and schools. This has been true for decades in the US, as cities are starved by federal and state governments. Now, the budget cuts are coming to cities in China. As in the US, lack of money for government translates into lack of money for services, maintenance, salaries, schools. A good example is from this Bloomberg story about Hegang in Heiliangzhang – China’s $23 trillion local debt crisis threatens Xi’s economy. Hegang was a coal town – think of small towns in Pennsylvania. Read a bit from this story and see if any of it sounds familiar –

Hegang’s residents are now feeling the brunt of the fiscal clampdown. During a recent visit to the city, locals complained about a lack of indoor heating in freezing winter temperatures, and taxi drivers said they were being slapped with more traffic fines. Public school teachers worried about rumored job cuts, and street cleaners endured two-month delays to their salaries.

The line of empty storefronts is familiar in many American towns –

Above, a shot from Gary Indiana. It is a mistake to see American city decline as anything other than the result of policy.

Above, a shot from Gary Indiana. It is a mistake to see American city decline as anything other than the result of policy.

A line of empty shops in Hegang in March. The heavily indebted city was forced to undergo unprecedented financial restructuring. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Continuing the Hegang story –

Outside the city’s largest hospital, a middle-aged orderly wearing green scrubs and a mask said her employers unilaterally changed her work contract from a government-run medical facility to a third-party vendor, reducing benefits like paid overtime for working on holidays. Her monthly wage of 1,600 yuan ($228) had been delayed by more than 10 days every month since late last year.

“I’m upset about the situation,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified in order to talk freely about her work conditions, as she pushed a wheelchair loaded with flattened cardboard boxes to an outdoor recycling point. “Everything is so expensive. I can barely get three square meals a day.”

This is by no means an isolated situation. One can certainly fault local fiscal mismanagement. But just as in the US, the greater responsibility falls on the larger governments and technological change. In both countries there are certainly problems from changing sources of energy and business relocations. The end result is lack of demand for local retail and lack of money for local services. But for many cities in the US, the source of the problem is fiscal strangulation by suburbs, and lack of state and federal money. In China the source is vast overspending on infrastructure. It appears that neither capitalist US nor socialist China is doing a good job of taking care of people. In both countries though, we see a common pattern of socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor. In major cities in China, health care and education quality can be very good, and schools are free up through high school. In some suburbs in the US, health care and education quality can be very good, and schools are free (via property taxes) up through high school. In rural areas in China, health care and education quality can be very poor. In poor areas of the US, urban and rural, health care and education quality can be very poor.

In both countries, governments will be forced to spend more on social services in the coming decade, against the will of oligarchs in both places.

At the same time, cities are being forced to cut salaries in the range of 15% to 30% to save money for services and debt service. I know this to be the case for the police department in Hangzhou. Lower salaries, greater responsibilities, and lower pension and health care quality are the way American cities deal with the same sorts of revenue strangulation.

Inequality

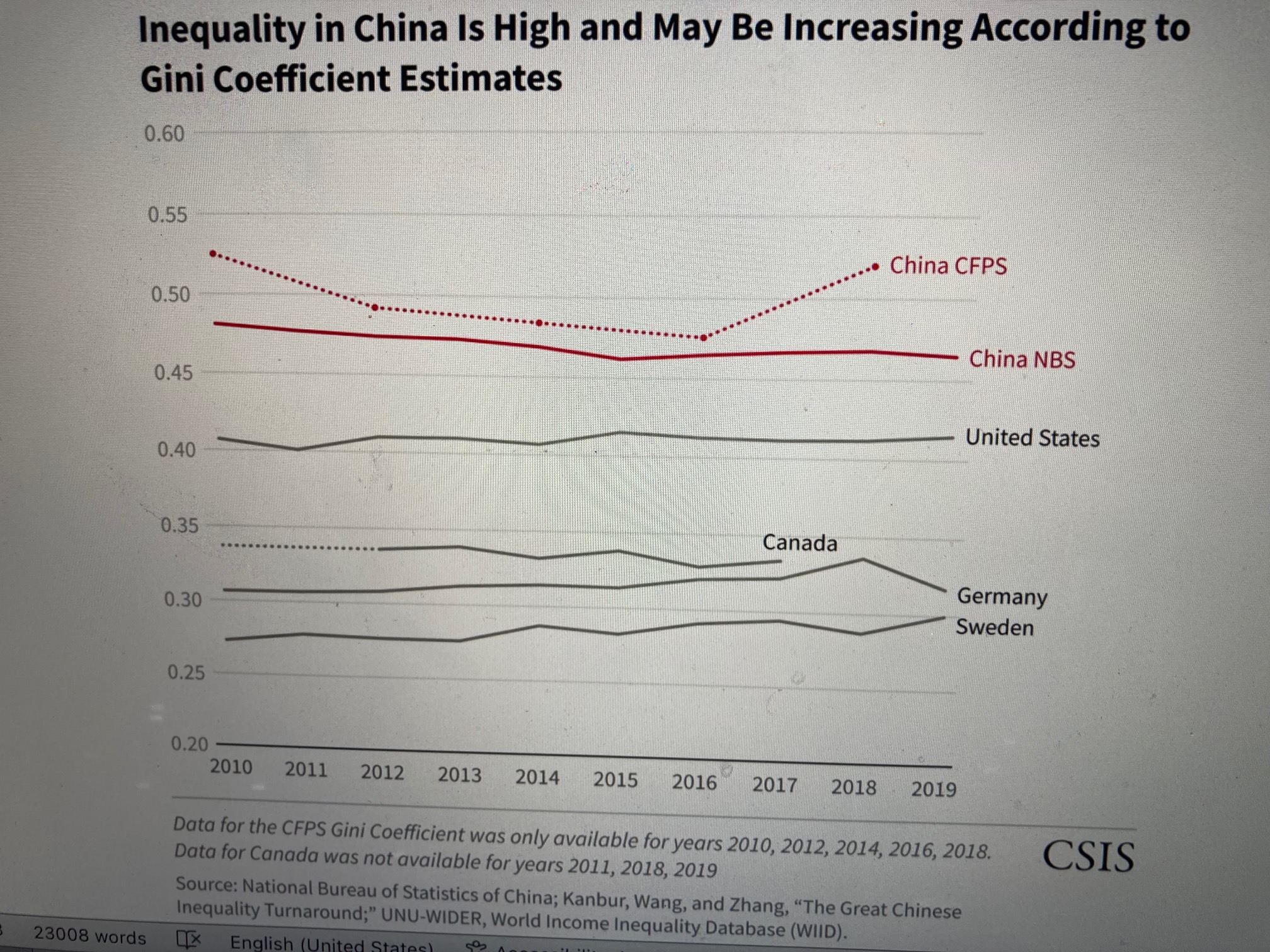

The Gini coefficient is a measure of inequality, usually measuring wealth or income inequality. The measure is between 0 and 1, with 0 meaning incomes or wealth are perfectly equally distributed, and 1 meaning that one person has all the income or wealth. A high Gini suggests that there is a wide gap between the wealthiest and the poorest. The US at about 0.40 is considered the most unequal of the western countries. The Gini is now much higher in China than in the US. The National Statistics Bureau uses a Gini of about 0.46; more trustworthy estimates are much higher, perhaps 0.52. Not news to anyone now, but a bit sobering to some purists that the greatest capitalist country is less unequal than the greatest socialist country. But both are far more unequal than any of their developed peers.

In China the top 1% wealthiest of the population own about 37% of the national household wealth. The next 100 million (7% of the population total) of the population own about 14%; the remaining 1.3 billion people, about 92% of the total population, own 3% of the national wealth. One can certainly quibble with these percentages, but the general direction is accurate. Above data from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, via the China National Statistics Bureau – CSIS, using data from the China National Statistics Bureau –

Another source – https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/china/income-distribution

China income shares by decile circa 2019

1st quintile 6.7% lowest incomes

2nd quintile 10.7%

3rd quintile 15.2%

4th quintile 22.0%

5th quintile 45.3% highest incomes

Highest 10% 29.5%

Lowest 10% 2.8%

Estimates of US income shares by the Federal Reserve say the top 1% in the US holds about 31% of national wealth; the middle 49%, about 66%; and the bottom 50% held 2.4%.

Note on the chart below – CFPS is China Family Panel Studies, an annual survey of families and individuals conducted by Peking University. It is considered more reliable than the government data.

Inequality is more than just a statistic. High inequality undermines growth and we interpret that as low shares of consumption in GDP statistics. For at least a decade, perhaps two, China has had the lowest share of consumption in GDP anywhere in the developed world. But there are deeper problems. From How Inequality is Undermining China’s Prosperity – inequality leads to poor educational outcomes for kids, poor healthcare for parents and kids, and a substantial share of the population that is unable to qualify for high-skilled jobs of the future.

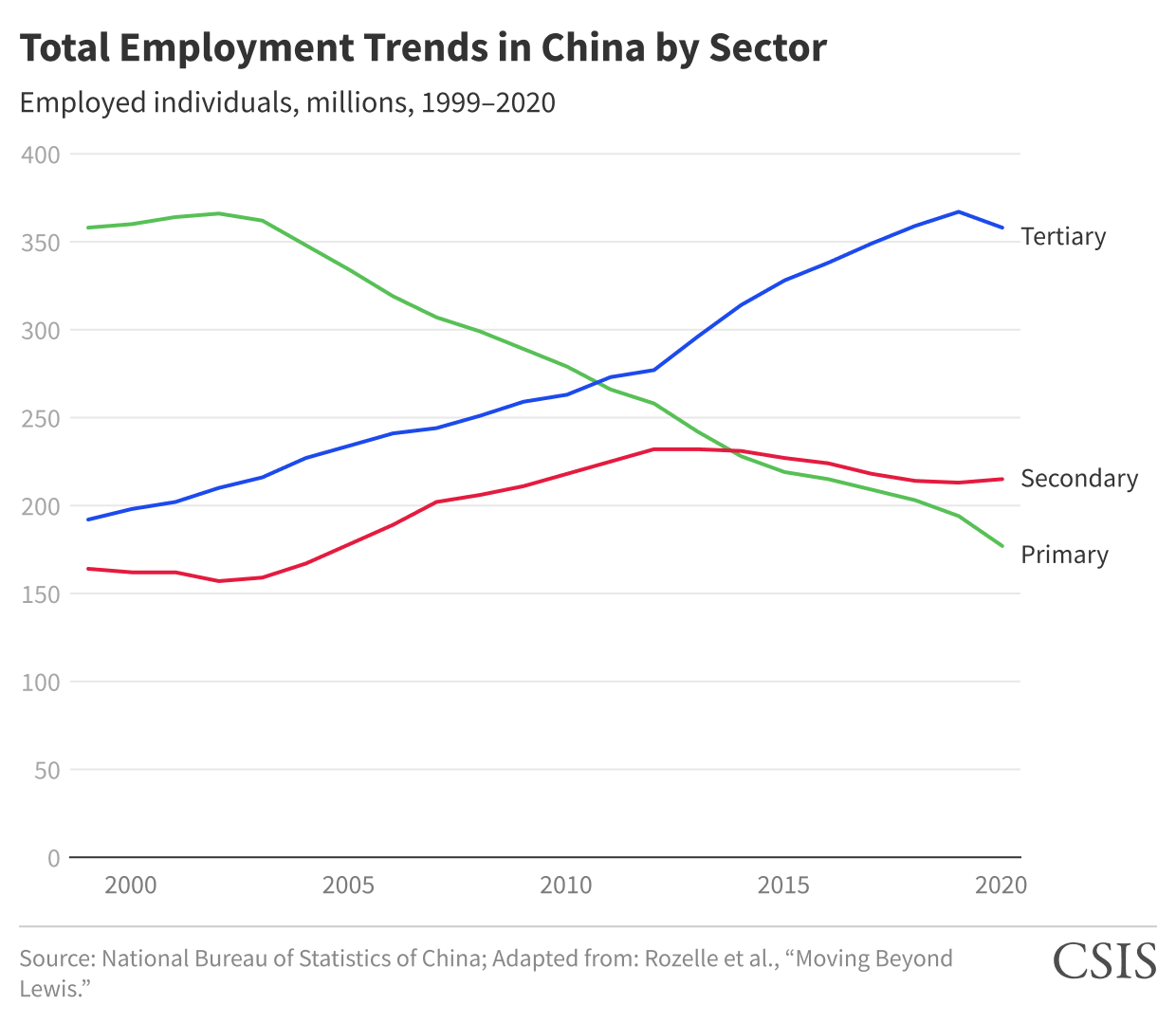

Primary sector jobs (farming, mining, fishing) have been in decline in China for twenty years. Secondary sector jobs (construction, manufacturing, assembly) peaked around 2012 and are in decline now. Current animosity toward China and Chinese products and within China the mistrust of real estate means this sector will not exhibit much, if any growth. What is left is the tertiary sector, which consists of retail, services and office jobs of all sorts. This is where there is growth. But this sector is far too small considering the enormous size of the population, and the majority of that population cannot afford to take advantage of most of the services offered (think law, marketing, advertising, accounting, medicine, teaching).

Taking a closer look at the data reveals even more about employment trends in cities. The service sector includes a wide variety of jobs, which are usually categorized as either skill intensive (e.g., the technology, finance, culture, education, and health) or labor intensive (e.g., retail, hospitality, and logistics).

While overall service sector employment has been increasing, when disaggregated between skill-intensive and labor-intensive jobs, the latter has been growing the fastest. In fact, labor-intensive services appear to be absorbing many workers who previously went into construction and manufacturing….

“Labor-intensive services” tend to be gig jobs or jobs requiring little training and therefore few long term prospects. There are more than 200 million of those jobs now. In that sense, the US and China have a similar problem with rural or urban labor that is insufficiently skilled for the jobs available. The sort of labor polarization that has taken place over the last forty years in the US – increasing wages for skilled jobs, stagnation for low skilled jobs – is happening in China now. The hukou is fundamentally responsible for the polarization, not unlike apartheid in South Africa or suburban boundaries and zoning in the US.

Hongbin Li, Prashant Loyalka, Scott Rozelle, and Binzhen Wu. Human Capital and China’s Future Growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 31, Number 1—Winter 2017—Pages 25–48. Available at www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.31.1.25

The trend is particularly striking because overall employment has also not been growing significantly in recent years. The data portrayed in Figures 3 and 4 indicate that job opportunities in manufacturing and construction are declining, which Rozelle and his colleagues expect is due to a combination of offshoring, automation, and a slowdown in new construction.

China is, in fact, no longer a low-wage, low-cost manufacturing country. As the economy boomed in the mid-2000s, wages increased, curbing demand for workers in manufacturing. As a result, labor-intensive, low-end manufacturing (e.g., textiles and electronics) has been relocating to Bangladesh, Vietnam, and elsewhere. The construction industry, a reliable driver of employment for decades, has also slowed significantly in recent years. Official Chinese data indicates that employment in the manufacturing sector has been declining since 2013. Finally, increased automation may also be hurting job opportunities for workers in lower-skilled occupations.

Importantly, the quality and security of work available to those entering the labor-intensive service sector are not equivalent to those available in manufacturing. Many labor-intensive service jobs are not regulated by the state or officially reported, meaning they are part of the informal economy. NBS data from China’s government statistical system show that informal urban employment is growing and today accounts for almost 60 percent of all non-agricultural workers, up from 40 percent 15 years ago. It is clear that the labor-intensive service sector—which includes a broad variety of jobs ranging from nannies and drivers to food stall workers and roadside repairmen—is driving this trend. Also, most of those working in these positions are migrants from the countryside who lack an urban residency permit (hukou), which is necessary to access a variety of welfare services, including pension benefits, healthcare insurance, and unemployment insurance.

If one wants an explanation for China’s current and future economic difficulties, one can start with these statistics. Those 20 or 25 per cent of the youth population that is unemployed don’t have jobs because too much of the wealth is owned by government, SOEs and the top 1%. I know quite a few wealthy Chinese. They have lives similar to or better than lives of their economic peers in the US. They eat well, buy extravagantly, travel, spend money freely. But their spending doesn’t help most Chinese very much.

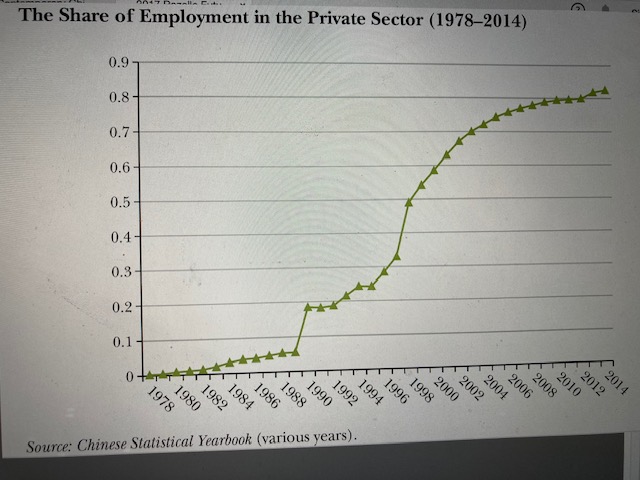

About 80% of employment is in the private sector (compared with about 85% in the US).

Private sector share of employment in China –

Source: https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.31.1.25

Hongbin Li, Prashant Loyalka, Scott Rozelle, and Binzhen Wu. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Volume 31, Number 1 Winter 2017, pp 25–48.

The private sector (as defined in China, probably to include SOE) is about the same size as the private sector in the US. Per the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) there were nearly 118 million private sector jobs in May 2020, representing 85 percent of U.S. employment. State government had 4.6 million jobs (3.3 percent) and local government had 14.1 million jobs (10.1 percent). The public sector employs 20.2 million people in the US, approximately 14.5 percent of the workforce.

Inequality in China is largely about the hukou, which restricts where people can live, work, go to school, and receive public services. The path to acquiring an urban hukou and accessing the benefits that come with it is arduous. Provinces and cities make up their own rules, and the central government and some provinces have been proposing to end or modify the hukou requirements for a decade or more, but little has changed. In some places, ability to buy an apartment may be sufficient to get the local urban hukou. Zhejiang Province is starting an experimental program to grant citizen hukous to Zhejiang peasants. In all of China there are about 900 million peasants now who have only a peasant hukou.

In any case, the consequences are that a large segment of the population lives in relatively precarious conditions. In 2014, only an estimated 16 percent of rural migrants working in cities were covered by pension benefits, only 18 percent had urban health insurance, and only 10 percent had unemployment insurance. This points to a different source of inequality that is not captured by income trends and is harder to quantify, even though it affects people’s lives in a very direct way.

People prosperity vs. place prosperity

In standard economic development terms, public policies can work to enhance businesses and real estate – tax breaks, hold interest rates low, subsidies to companies, free training, sales of land at low cost or preferential market access – or work to enhance the welfare of people – health care, social services, education, pensions and wages. Place prosperity is the usual form for public policies for a variety of reasons. Businesses and real estate are local and locked in. Their productivity and jobs are difficult to move. Fundamentally, governments Understand real estate in a way that they cannot understand businesses. They can easily tax and regulate the physical environment. Building things is ego-supporting for politicians of all stripes, in the US and in China. “Look what I did.” It is the edifice complex for politicians and architects.

Supporting people is difficult. It takes a long time – maybe a generation – it is not obvious in the way that new buildings are obvious, and its output is uncertain. People can move away after they have realized the benefits of good social policies. The end result, if done reasonably well, is a better balanced Gini coefficient and a large middle class that can support more jobs, more consumption, and greater stability.

But both the US and China will need to do much better on people-prosperity in the next few decades. There is plenty written on this topic. Just a couple of citations – Zhang Jun, Dean of the School of Economics, and Director of the Research Institute of Chinese Economy at Fudan University at Pekingnology – Low wages threaten China’s economic transition, government needs to subsidize families. Michael Pettis has been making this argument for more than a decade. A recent post – Can China’s Long-Term Growth Rate Exceed 2-3 Percent? China must invest less, consume more and the government desperately needs policies to allow that to happen. Pettis sees US debt as the mirror of rising Chinese debt. Sort of a “one hand washes the other” phenomenon.

Essentially, both countries need to bring down their respective Gini coefficients, which means making for greater wealth equality. This means greater taxes on high earnings, broader coverage and collection of taxes and less support for the oligarchs in both countries. The Chinese government will need to bail out cities as the US bailed out banks and finance.

Pettis makes the point clearly in his recent book with Matthew Klein Trade Wars Are Class Wars. The US and China share another similarity, in the complementarity of their macroeconomic models. Some mainstream writers want to posit China as the evil supplier of goods, and American consumers as willing fools in the transactions. The American trade deficit with China is not of our creation, it is said, it is due to those low paid factory workers in China. Pettis and Klein make the point convincingly that both the US and China privilege particular people at the expense of others – manufacturers and exporters in China, banks and finance in the US. In both countries, conditions for working class people are suppressed – wages, education, health care, social services – so others may be privileged. The argument is more than I can make here, but my point is that the US and China have shared a commitment to the upper level of the income distribution at the expense of others. One can see in this model a good part of the current distrust and discontent in middle and lower classes in America. The “Dream” is not working.

I keep waiting for Pettis to get the Nobel Prize he so clearly deserves.

From Klein at Overshoot – Our book argued that income concentration over the past few decades has undermined global growth and financial stability…. In our view, the main risk associated with egalitarian redistribution was the potential for growing geographic mismatches between who was doing the additional spending and who was doing the additional production, which had the potential to translate into unsustainable financial imbalances.

Klein’s use of egalitarian here is a global egalitarianism – middle class Americans giving up their jobs in favor of peasant Chinese. The mismatches are a result of policy choices, not some abstract macro theorizing about how the world works.

In other words, the trade imbalance is a symptom, not a cause, of economic difficulties – like the cost of raising a child, or the cost of health care or education. Its not the fault of China or CCP.

Corruption

Corruption is not unknown in American government and business. Based on my own experience in Chicago, for decades a leader in municipal corruption, local “street level” corruption seems much less of a factor now than I ever recall and it seems to have moved more into deals arranged in board rooms from deals on the street. Corruption exists, but payoffs for building permits and getting out of a speeding ticket are now rare. Even Illinois, also a long term leader in state corruption, seems now less corrupt than in memory.

Real corruption now is at the state legislature and federal scale, where large companies and wealthy donors and funds write legislation to their benefit and use promises of money and jobs to defeat legislation and regulation that would be of benefit to most of the population. Two examples of many – Why Are Corporate Healthcare Fraudsters Being Handed “Get Out of Jail Free” Cards? and Here’s how states can end corporate welfare. At the local level, I gave political donations to aldermen in wards where I was wanting to do real estate development deals. This was never considered corruption – it was just a donation to promote the good work the alderman was doing in the ward. No quid pro quo, ever. But one was buying a little bit of guanxi, Chicago style.

In other words, American corruption has come to look more like Chinese corruption – less on the street, more in the boardrooms and government offices. Key evidence comes from recent Supreme Court revelations. No need here to rehash the Clarence Thomas-Neil Gorsuch-John Roberts shady dealings. And I leave it to others to parse legal arguments of their …. forgetfulness about reporting, if not about ethics.

In China we see the stories of high level corruption all the time. Not a day goes by without reports in the Chinese press about a local, provincial, or national figure in a bank, SOE, or unit of government being detained for “violations of Party discipline” which is the euphemism for financial corruption, generally accompanied by violations of personal moral probity. The health care business is well known for its corruption, with drug and equipment suppliers regularly going through a “pay-to-play” scheme with hospital leaders.

The land thefts that deprived hundreds of thousands of farmers of their land in favor of commercial development, proceeds of which went partly to local officials, are now less. The hated chengguan, city street monitors, seem to murder and beat farmers less often now than a decade ago.

For purposes of comparison, I offer an insightful article by Ling Li, Performing Bribery in China – Guanxi-Practice: Corruption with a Human Face ((Journal of Contemporary China vol. 20, no. 68, 2010, page 1-20. Ling Li teaches Chinese politics and law at the University of Vienna). Li asks –

What is “the way” in which bribery is supposed to be conducted and what makes the so-called guanxi-practice special? She comments The enabling role of corrupt participants seldom attracts academic attention. Enabling in this context means that once the motivation of corruption has been established, corruption actors can also strategically plan their conduct to overcome the legal, moral and cognitive barriers, which are supposed to obstruct corruption. In order to investigate this enabling factor, one has to look into the interacting process of corrupt exchange at the micro-level.

Li defines corruption as the misuse of entrusted power in exchange for private benefits.

Corruption in business and government dealings in China is a cultural meme. Cultivation of rich and powerful people for corrupt purposes, like judges, is daily fare. Current news is about a central government crackdown on corruption in medical and pharmaceutical fields.

From Caixin –

The crackdown is targeting six areas, the National Health Commission (NHC) said in a statement Tuesday. They include rent-seeking by health administrators; bribery in service providers run by health administrators; illegal drug trading by pharmaceutical companies; kickbacks in medical institutions and the sale of drugs, medical devices and consumables; misuse of health insurance funds; and integrity breaches by medical personnel.

In an interview, Hu Gang, the author of Celadon, revealed that he had spent half a year to build trust with a high-court judge before he was given the first court commission. In colloquial Chinese language, this strategic trust-building process is exactly what guanxi-practice is about.

For the last irony, Li herself concludes with a sentence that could end any American Supreme Court story –

It is rather ironic that contrary to the views advanced by some western China scholars, who attempt to distinguish gifts from bribes, and guanxi-practice from corruption, guanxi-practitioners are striving to blur these boundaries. The very existence of equivocation, excuses and camouflage, so characteristic of guanxi-practice, demonstrates a shared sense of awareness of the illegality and impropriety of the conduct. Were it not for this awareness, such a heavy-loaded masquerade would be meaningless. In fact, the very term of “guanxi-practice” is a euphemism, used to conceal the confrontation with the “unsettling topic” of corruption.

Something about if it walks like a duck ….

If anything, a code of ethics would mean some existing relations might have to be curtailed to avoid the hint of impropriety. But we have to wonder – if corruption can be so easily identified in China, and it looks pretty much identical to guanxi practice in the US, what can we say about justice with American characteristics?

Homelessness

There are plenty of Chinese who are able to sleep amidst roadside landscaping or hovels located amidst far more prosperous surroundings. It might be hard to tell who is homeless and who is not; there were a number of people living in makeshift dwellings on the periphery of our school in Hangzhou. They weren’t technically homeless, but their homes were certainly contingent and about as secure as the tents we see in parks and on streets in the US.

The hukou still makes homelessness less of an issue in China than in the US. Theoretically almost everyone has a home to go back to in some village somewhere. Homelessness is likely to be of migrants who’ve lost a job, with its attendant blue-roof metal shed temporary worker housing or the mentally ill. Some homeless might be disabled or Chinese evicted from their long term housing by government redevelopment demolition of villages. This Radio Free Asia story Down and Out in China is a bit old, but likely still pertinent –

In the southern city of Guangzhou, a 2008 survey carried out by the Guangzhou Municipal Homeless Shelter Management Station and Zhongshan University interviewed 600 homeless people and ordinary citizens.

It found that the majority of homeless people were men between the ages of 20 and 60 who had suffered financial ruin or loss of employment, had a disability, or had been injured in industrial accidents.

Some were found to dislike work, while others went out begging to take care of dependents.

While 60 percent of those interviewed had been beggars for more than a year, 18 percent had been on the streets for more than a decade.

Governments at the county level are required to take active measures to rescue homeless people and beggars in a timely manner. A good part of that assistance is to provide payment for transport back to a person’s home village, where presumably family would (necessarily) look after them. The close relatives are to be educated in their obligation to provide support.

Characteristics of American homeless are here. American homeless usually have no family place to go. There are social services available for some.

Peasants

There are significant portions of the population in both countries who are informally shunned by middle class.

Nongmin is the Chinese term usually translated as peasant. It is the hukou designation for people who are not citizens, who are gongmin or shimin (city persons). Nongmin does not mean farmer in this usage. There are peasants who are not farmers. Peasants are generally thought of as poor, uneducated, believers in spirits and generally unable to take part in the great Chinese rejuvenation. While CCP gives the nod to peasants – the first State Council document in every year has to do with farm and agricultural policies – middle class Chinese ignore peasants at every turn. Researchers discuss the shunning at length – Muddled Modernities in Peasant China and The Law Cuts Both Ways: Rural Legal Activism and Citizenship Struggles in Neosocialist China.

In the US, poor people, particularly poor minorities, are shunned. In China the hukou restricts where nongmin can live, their employment, living conditions, health care, and education. In the US, that function is taken by suburban zoning restrictions and land values. In both the US and China, parents change their residence to be in a good school district and will not tolerate their kids going to school with peasants. Minorities in the US and peasants in China have often been disregarded in actual policy, even though the governments make promises and proposals for assistance in education, jobs, health care, and social services.

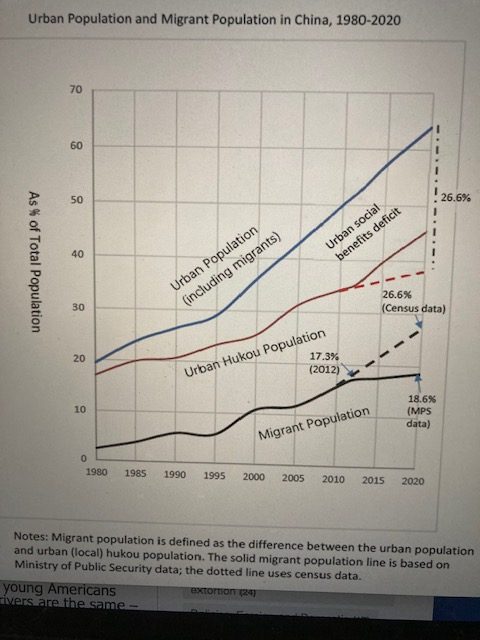

Urban and migrant (peasant) population and the social services deficit –

This figure illustrates an enormous problem for China. About 26% of the urban population does not have an urban hukou, and is therefore ineligible for local social services, including education, health care, pension and unemployment payments. This is essentially a defeat of the original intent of the hukou policy, which sought to keep city wages high and rural wages low through strict separation and keep peasants from clogging up city services, as was seen in the US. Now the peasants are there, and in numbers far too big to send back home to some rural county.

Gig jobs are made for peasants trying to live in cities in China; as they are for young Americans trying to make their way. Some conditions for bicycle or motorbike delivery drivers are the same – poor job conditions, unreasonable pay requirements, no benefits or future. Two articles, one on gig jobs in the US, the other on gig jobs in China – My Frantic Life as a Cab-dodging, Tip-chasing Food App Deliveryman and Feeding the Chinese City.

Health care

Doctors are generally honored in both countries and the medical system is deeply systemically flawed in both. Both have problems with quantity and quality of health care in poor and rural communities. It is difficult to get doctors and nurses to work in rural areas. Both countries have problems with insurance coverage that makes people avoid care, have to shop for care, and ration their own care. About three-quarters of Chinese do not have health care insurance through their employer, and must depend on a government bare-bones program, which covers little. The three hundred million migrants who have built China and stoked its factories over the last two decades do not receive any health care benefits through their employer. More by Winnie Yip from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health – Disparities in China’s Urban and Rural Healthcare.

China has a particular problem with expectations that honored doctors will fix whatever problem they attend to, or save lives regardless of the stage of illness. There are many cases of doctors and nurses being physically attacked by families dissatisfied with medical outcomes, with police posted on some surgical floors. It is not clear whether the attacks follow payment of hong bao, customary red envelope gifts to doctors in support of special care for a family member. Perhaps surgeons in the US make enough money so hong bao contributions are unnecessary. Nevertheless, attacks on health care workers in the US are on the rise. Not a story I expected to read – Attacks at US medical centers show why health care is one of the nation’s most violent fields.

There are issues of trust in the medical system in both the US and China, although for different reasons. In the US, particularly in rural or low-income areas, the government may not be trusted for political reasons – witness the refusal to accept medical advice on covid. In China, lack of trust might lie in doctors who use western medicine rather than traditional Chinese medicine and a historical lack of trust in a private system of care. A private system is based on a profit motive, and why would that work to the benefit of the patient.

It doesn’t seem necessary to discuss health insurance problems in the US, both expense and coverage and shopping for care. But China is similar to the US in some respects – coverage can be excellent depending upon one’s position and location. In Hangzhou, a modern sophisticated city, I was treated for a bad cough. Went to one of the local hospitals – a good one, paid 15 yuan (about $2.50) to see the doctor, followed the signs (in both Chinese and English) to the appropriate office, waited just a few minutes, went in and talked with the doc, who gave me a prescription. We talked for a while. His English was so good, I bet we could have discussed basketball scores. He prescribed a known American medicine, which worked fine. That was good enough, he said. I wasn’t sick enough for him to prescribe Chinese medicine.

I’ve written about doctors and hospitals for pregnancy – here and here. In the best hospital in Hangzhou – again, a modern sophisticated city – chaos is hardly the word to describe the crowds, the lines, the frantic pushing and shoving, the degrading lack of attention to patients. It is libertarian-style health care run amok.

My daughter went to a small clinic in Jingzhou, a small city in Hubei Province, treated for a cough and bad stomach pain. No waiting, communicated well and got some medicine, which worked fine. Not sure if we paid anything at all.

The US system is stupidly expensive and requires intimate negotiations among patients, providers and insurance companies. Much time is lost in negotiating the particularities of medical coverage codes and what part of normal treatment is covered and what is not. Whether one can receive treatment is a function of whether a particular hospital, or worse, a particular doctor in the same hospital, will accept your insurance coverage.

The Chinese system is not nearly so expensive, but can still require negotiating among hospitals as to which hospital will take a patient. I know of a case in which a hospital could not provide needed coverage, but refused to transfer the patient to a better hospital because the hospital would lose the money from the insurance program. This was treatment for my brother-in-law. Only some complicated guanxi enabled the transfer to take place. Hospitals regularly refuse to take patients from outside their city or province, since insurance programs are location-specific.

https://www.coresponsibility.com/chinese-healthcare-the-rural-reality/

There can be world class health care in cities in both the US and China. In both places, proximity to excellent facilities and doctors does not ensure care. Care is determined by access to insurance, which in the US is determined mostly by access to money and in China mostly by access to CCP or a state-owned business. Private businesses and government agencies provide health care insurance at widely varying levels of coverage. Both countries have serious problems providing adequate care in rural areas.

From an excellent report from ChinaPower at the Center for Strategic and International Studies – The level of health care available in Beijing, for instance, is comparable to some states in America – such as New Hampshire and California. Mississippi received the worst score within the United States. Health care in Mississippi is rated lower than that in ten Chinese provinces…. The costs carried by Chinese citizens vary considerably. Tibet, one of China’s poorest provinces, ranks in the bottom third globally in health care access and quality.

A 2014 study conducted in the urban and rural communities in Suzhou revealed that residents under the rural plan were only reimbursed for 57 percent of their medical fees – far less than the roughly 70 percent reimbursement rate granted under China’s urban health care plans.

Universal health insurance and care for seniors is provided by the government through Medicare in the US, and for low income people through Medicaid.

There are no similar programs in China. If care is not provided through a pension or retirement plan, then it doesn’t exist, other than a very bare-bones national plan for peasants.

In China the historical pattern has been that government provides little to no social services – not education, not health care, not care for elderly or the disabled. Families and clans and lineage groups were to provide. (This is the China that libertarians must dream about.) Times are now different, but it is still the case that city or county governments provide services for urban hukou holders, and villages provide services for villagers (usually little to nothing). That too is changing, but there are wide inequities in social service provision between those who are poor and not poor, and between city and rural residents.

In China the health care stupidities come in with poor coverage and grossly inadequate staffing. (I’ve written about the mob scenes of pregnant women surrounding doctors and the lunacy of standing in line for long times, maybe hours, just to get a number to get in line later to see a doctor. And no number, no doctor. This, at the best pregnant woman’s hospital in Hangzhou.) Those with adequate guanxi don’t need to stand in line, though. There are special times for special people.

In the US the health care stupidities come in with extreme costs and coverage decisions made by insurance companies rather than doctors. Inadequate staffing and poor pay are American stories as well.

Poor rural health care is a shared deficiency. Rural hospitals are closing in the US and there is an acute shortage of trained staff. Current GOP policies and financialization of medical care suggests that these shortages will get worse. In the mid-term, say the next ten years, both countries will need to spend a great deal more on health care and pensions and less on physical assets, infrastructure in China and the military in the US.

Education

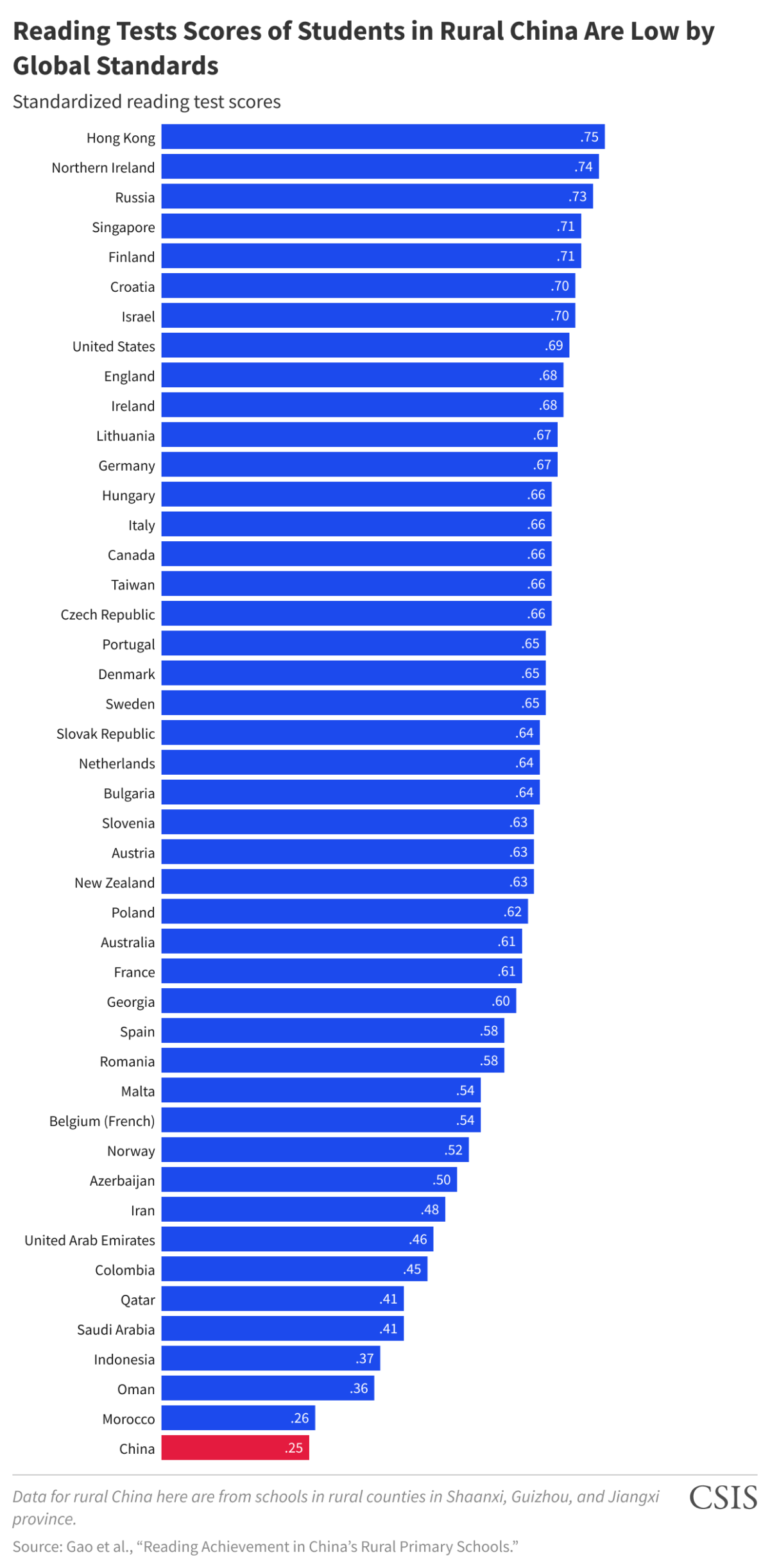

In both countries there are excellent schools and poorly performing schools in the same political jurisdiction – Beijing, Hangzhou, Shanghai and New York, Chicago and Los Angeles have examples of both. Excellent schools can naturally lead to sophisticated and high-paying jobs. For students in poorly performing schools, the chances of joining a modern hi-tech economy seem poor.

Conditions in primary school education for poor and minority kids in China are like those for poor and minority kids in the US. Difference is mostly that these kids in China are rural, in US they are urban. But similar problems – poor teacher training, poor teacher quality, low pay, stupid requirements, sometimes language problems, sometimes parents that are absent or don’t really care, grandparents who don’t care or can’t help a kid with schoolwork, families that want the kid to help bring in money instead of going to school, poor support in the environment, high dropout rates, and a bunch of programs mostly non-governmental to help a few kids. And middle class Chinese and American parents do not want their kid going to school with some peasant or minority kid. So, parents move to get into a “good” school district. Funding for schools in China is at the county level, so rural counties that produce little GDP have a tough time. Not sure, but maybe no funds from central government at all. Not so different from American urban school districts starved by lack of funds from the surrounding suburbs that revel in their proximity to the urban core without having any of the responsibilities.