Summer and Fall, 2012

(reader note – this is a bit long, but has some details about hospital care. Forewarned is forearmed)

A while ago, I wrote about mysteries of the parking lot market in Hangzhou.

There are procedural mysteries everywhere in China. Systems that are clearly not care-full of the needs of customers, but at the same time, seem not to be in the interests of the provider. Hospital operations are another good example. Take the Zhejiang Pregnant Women’s Hospital, one of the AAA rated hospitals in China. Or the Hangzhou No. 1 Hospital, across the street from the Pregnant Women’s Hospital, another AAA facility. Or, I surmise, most any hospital in China. The systems, both physical and procedural, seem chaotic, redundant, and stupid, for every human inside the building.

It is supposed to be a sophisticated management insight that systems try to optimize. Something. Maybe not customer satisfaction, but maybe management benefits, or leader salaries, or bureaucratic time. Profits. Maybe it is hard to see what is being maximized or minimized, but by default, something must be.

Hospital Rules has two meanings here – the procedures and requirements that any organization must impose to maintain order; and the peculiar implementation of rules in hospitals in China for which the only discernible purpose is to grind the customers into submission. The administrative system – the Rules – uber alles.

Source: my Experience at a Chinese Hospital http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2014-04/23/content_17455961_2.htm

So we think that hospitals, like any other institution, anywhere, are maximizing someone’s comfort, someone’s benefit. Could be doctors – we think that, in the US. Could be hospital administrators. Or insurance companies. Or the government. No one thinks the system maximizes patient care. Certainly, no one in China thinks that. Maybe benefits accrue to no one physically at the hospital – maybe it is the government officials in charge of setting standards for hospital procedures, or those benefitting from contractor or developer kickbacks, who are many years gone from observing the actual operation of a hospital, but nevertheless profited from designing hospital systems.

That could be. Architects are notorious for maximizing their own interests, to the detriment of the customer or the operator. The system in China could be maximizing the interests of some group of original hospital designers. Flow charts and department layouts and coordination with other hospital departments. Flow of paperwork, flow of people, flow of medicines and blood vials and cleaning supplies and band-aids. It is no accident that hospitals are laid out as they are.

In China, the physical design admirably reflects the lack of concern for normal procedures. It is as if all these people showing up every day – who could’ve known? It is not as if the hospital layout was designed in the 1920s, and modern medicine needs different size rooms and storage areas for equipment, and wall space for oxygen and air and ten other fluids, and the poor old buildings are just trying to cope. I mean, the floor layout, and the room sizes, are entirely appropriate to the battlefield conditions one finds in the hospitals at any time of day. In other words, the battlefield conditions are built in. The Pregnant Women’s Hospital is really a Chinese MASH unit – maternity and standing hospital. God forbid that pregnant women would want to sit down.

You can probably guess by this point. I do not suggest that hospital procedures are designed to maximize patient comfort or satisfaction. But let me give you some details. The hospital system, like many systems in China, is designed for grinding. Grinding people, to the point at which they give up protest, or resistance, or care about quality, and settle for … whatever the system provides. Animals will protest when you beat them, but if you beat them enough, they will work for you. Power maintains its privileges through mystery and struggle. Power, in the hospital system, may not be maximized, but it is conserved. The system uses just enough mystery, just enough struggle, to retain its privileges and force the patients, and their spouses and assistants, to submit.

The Pregnant Womens’ Hospital in Hangzhou has multiple entrances. In a place with hundreds of people going in and out at any one time, this probably makes good sense, not to funnel everyone through one set of doors. But the physical hospital layout exhibits one of the Chinese characteristics in building that I just cannot get over, unless one considers the role of mystery in Chinese culture.

This is the penchant, everywhere, for making building exteriors indistinct and their interiors confusing. We all like buildings that are not foursquare boxes; but we also appreciate when a building tells us something about where to go, or how to get there, whether with signs or design. Chinese hospitals do neither. Mystery is a key design principal – the less you know about how a building works, the more power the building management has over you. Not that the management really needs to exercise power over patients; patients are already at something of a disadvantage by walking into the hospital. But mystery, whether in design, or communication, supports power.

At the Pregnant Women’s Hospital there are three main hospital buildings, all built at one time. It is a hospital, so you don’t expect every floor to have the same layout, but you sort of expect some connectedness in going from building to building, especially at the first floor.

But you can’t walk from building 1 to building 2, or building 3, by any means other than by walking through an alley, crowded with moving trucks and cars and people, and then by narrow hallways full of old computers and hospital equipment lying around the corridor. Sort of like the garbage dump inside the spacecraft in Star Wars, into which Luke and the Princess and Han get dumped, and the walls start closing in on them. No scary underwater creatures, though. We are not really in a movie. Too bad. That would make more sense.

And it is not in the design, people were not expected to walk between buildings. They must walk between buildings to get different pieces of their own health care. But the unclear physical layout is the beginning of the mysterious Chinese process of grinding down, by means of design. Some more examples –

There are generally no clinics, or individual doctor offices in China. When someone has a cold, they go to the hospital. And even in the Pregnant Women’s hospital, with multiple entrances, everyone has to pay first, before service. I have used hospital emergency rooms two times, and even then someone has to pay for you before you get served. If you are dying, or bleeding profusely, or in extreme pain, make sure you have at least two people to go with you to the hospital – one to drive the car, and wait in line to park while you go inside, and one more person to stand in line to pay for you. Bring some money, as well. Not a lot, maybe a few yuan, but fee for service is the operating principal much of the time. If you need help getting upstairs to see the doctor, bring another person. (Actually, fixing these inappropriate procedures would cut down significantly on the crowded conditions – no one looking for emergency treatment would dare come to the hospital alone).

Now, about paying for service – this can get complicated. Sometimes, you can stand in line to pay, tell the cashier what is wrong with you, and they will charge the appropriate amount and give you a receipt to get served by the doctor somewhere else in the hospital. Ok. But most of the time, it seems, you must have a signed note, sort of like an appointment, but not really, from the doctor before you can pay. So – you have to go see the doctor, stand in line at the doctor’s office, to “get a number,” as they say here, so you can pay before you go see the doctor. I am not kidding. This is not true for emergency procedures, but it is certainly true for most any normal procedure, including monthly trips to the gynecologist, in the Hangzhou hospitals.

Payment is always on the first floor, generally at least one floor and half a hospital away from the office where you had to get a number from the doctor. The patient, whatever condition they are in, if they can walk, they should physically carry the piece of paper with the number to the business office, where the payment can be made and the receipt will serve as admission to the presence of the doctor.

If you have sufficient guanxi, you can see the same doctor every scheduled pregnancy visit, every month or two weeks. But don’t get the impression that you call, get an appointment, show up ten minutes before the appointment, wait a little long, but get in within half an hour to spend a few minutes with your personal doctor, who knows your history and has your records and will more or less patiently listen to questions and provide answers. That would be a mistake.

First of all, no one in the hospital – not a doctor, not a nurse, not a technician, not an administrator – is reachable by cell phone, land line phone, email, text, twitter, or a sense of general human compassion. Phone numbers don’t exist or if they do, calls go unanswered. It is not possible to make an appointment for any service, whatsoever. When you want service, come to the hospital, and get in line. Face-to-face is the only form of contact. I would guess there is no patient advocate in Chinese hospitals.

Doctors are in short supply, and doctors don’t get to choose their patients, in any real sense. They have some control over how many patients they can take on, but the nature of guanxi means that a friend of a friend can always sort of impose on a doctor to take one more patient, and for the doctor to say no would mean loss of face for the person making the request, which one tries to avoid. So, doctors end up with far more patients than any medical standards off the battlefield would allow. But every patient is in the doctor’s office because of guanxi from somewhere.

The doctor gets into the office at about 8:30. Women who have previously seen that doctor, and are in some minor sense, her patients – have been lined up outside the office since about 6:30 or 7:00, waiting to get into the office to “get a number.”

When the assistant open the door, you can imagine the rush. It would be comedy, if everyone weren’t so serious. It would be sad, if this were a Civil War battlefield hospital, with men begging for care. Here, it is just outrageous and stupid. When the door opens, the twenty or thirty women waiting rush the door, and ten or fifteen make it inside the door. The losers wait outside the doctor’s office door, until someone walk out. The doctor is seated at a small desk, and the pregnant women, in various stages, are thrusting their medical records from three sides of the desk at the doctor. When the doctor take the medical records, the patient gets a number, which sets her place in line to – come back and see the doctor. Not a joke. When the doctor gives you a piece of paper with a number on it, you are IN. By this point, the winners feel pretty special. But that is how the grinding process works.

The wait begins. No one is going to see the doctor for half an hour or an hour, because the doctor is sitting at the desk handing out numbers, being on the phone, looking up information on the computer, answering urgently shouted requests from the horde.

Our particular doctor only has office hours one-half day a week, in the morning. If you can’t get a number for that day, you can come back next week or do something else, unspecified. But the something else does not include seeing a doctor in the next office. You did not develop the guanxi to see that guy.

For some people though, not getting a number from the doctor is no impediment to seeing the doctor. In our case, yesterday, the doctor gave out 28 numbers to see 28 patients between about 9:00 AM and about 12:30, when she would leave. The hospital itself gives out the first few numbers to see the doctor, presumably for the people who get to the hospital at 6:00 AM and before the doctor herself gets there. The number of numbers given out by the hospital varies, but sometimes the hospital gives out numbers 1 to 10. The doctor herself, on our last visit, gave out numbers from 16 to 33, for a total of 10 plus 18, or 28 patients.

But some women walked in with numbers, and their names in the computer, for numbers 11 through 15, that the doctor did not give out. She was a little pissed about the imposition, but this is extra special guanxi at work. Not only do these five women have a number that the doctor did not give out, their names are already in the computer for the doctor to see. She could refuse to see these patients, but even doctors have issues of guanxi to deal with, for promotions and more money and other mundane work benefits. So, 33 patients in about 3 and one-half hours, or about 10 per hour. Pregnant women who, in a normal world, should have questions, and fairly intricate questions at that, requiring thoughtful answers. Not to mention saying hello, and goodbye, and measuring the circumference of the stomach, and looking at records of blood tests and ultrasounds and other tests that might have been done in the time since the previous visit. And, constructing a story that makes sense about the medical history of the patient, to provide more tailored advice. For the sake of patient care, one hopes that the doctor never has to go to the bathroom, or have an emergency. In that case, everyone would just have to come back next week.

Actually, it is good that you have to wait. While waiting, you can go pay for the visit, because you can’t come back and see the doctor without the paid receipt. Or you can go weigh yourself, get blood pressure taken, or get a blood test. Or a nap. Befitting the battlefield conditions, there are people sleeping everywhere, propped up against walls and chairs, women sprawled sideways on chairs trying to get some rest, since they got up at 4:00 AM to take buses for two hours to get there by 6:00 AM, to get in line for an appointment at 11:45 or 2:30.

One needs to get the weight and blood pressure and temperature taken care of, on one’s own, in the interim waiting time to see the doctor, unless one wants to make the hospital visit into an all day affair. Any tests, or visits, that are not completed by 12:00 cannot be done until 1:30 PM or after. Why? Because the entire damn hospital closes down for 90 minutes, at 12:00, for lunch. The hospital closes down, like maybe a restaurant that closes for a couple of hours between the end of lunch and the start of dinner. The place that was teeming with humanity at 11:55 is like a ghost town at 12:15. At 1:25, it will be teeming, again. Of course, anyone in line at 12:00 when the doors slam shut can reserve their place in line at 1:30. Right. No. Even the line to pay, to give the hospital money, closes down. Now that is efficiency.

The line to pay for the visit is usually not too long, maybe five or ten or fifteen people in front of you, and it moves reasonably quickly. Maybe wait in line five or ten minutes, or a little longer. But there can be complications.

One time, the doctor wrote down the wrong id number for the procedure we were to get – I dunno, maybe she wrote down a number for “amputate both legs,” instead of “regular office visit.”

Not sure. But the cashier, ever precise, caught the mistake. The fee written down by the doctor was 5 yuan short. The hospital would have lost 5 yuan in that event, not to mention maybe Qing’s loss of legs. I graciously offered to pay the 5 yuan right then, change the procedure order number right there at the cashier, but there is no getting around the procedural maximization in the hospital.

Maybe you can guess. We had to go back up to see the doctor, to make the doctor correct her serious error. We rejoined the pleading, bleating mob in front of the doctor’s desk, and in only about 15 minutes we had made the doctor correct the id number for the procedure. No doubt, surrounded as she was by medical records and pleading women, she felt severely chastised by the downstairs cashier for making such an egregious error. No doubt the doctor will never make that mistake again. Cost to us in time, standing in line the first time, arguing with the moron cashier, going back upstairs to get the id number corrected, waiting to see the doctor again, going back downstairs to pay again, about 45 minutes.

You remember Steve Martin as the weatherman in Los Angeles, in LA Stories. His life was without care, the weather was always perfect, and he was … bored. Bored Beyond Belief, is what he wrote on his window pane – BBB. I am coining a new term, SBB, for procedural … complexity … in China. Stupid Beyond Belief. This fee snafu is a relatively minor example of an SBB moment. We can call it SBB – minor.

After getting the procedure number corrected, we went back downstairs, stood in line, paid 25 yuan, instead of 20 – about $0.50 difference – and went off to get the blood test.

It is not so easy to find aspirin in china. For some reason, aspirin seems to be one of those western things that don’t fit with Chinese culture. I don’t know why – there is certainly mystery about how it works. American pop aspirin like … well, aspirin. Chinese don’t. But blood tests are a different story.

Chinese do blood tests for … everything. If you come to the hospital for a cold, you get a blood test. If you complain of feeling badly, you get a blood test. I am pretty sure that if you complained that you did not have enough blood, the hospital would ….

Pregnant women get frequent blood tests. I am not medically savvy to know what they are testing for, so continuously, but the process is one of the scariest things I have seen in China. Regardless of the hospital, the procedure seems the same. Call it another SBB – minor, unless by mistake it becomes an SBB – major.

The blood test stations are designed to maximize throughput. There are ten to twenty service stations, behind a long window, at which technicians, not doctors or nurses, take blood test after blood test after blood test. There is room to insert your arm beneath the thick glass wall separating you from the technician. Sort of like transactions in a currency exchange in a dangerous neighborhood, or the takeout fried chicken place at 75th and Yates on the south side of Chicago. Just enough room to insert your arm for the withdrawl, which takes all of about ten seconds. The Hangzhou No.1 hospital across the street has a line system – get in line at one of the stations, wait for your test. Waiting time in line, ten to 30 minutes. Very democratic, though. Everyone gets in line. If you have a cold, and are coughing badly, get in line behind the pregnant woman lying on a hospital bed, who is behind the crying baby who looks about to explode or the guy bleeding rather a lot from a head wound. No special treatment in the blood test line.

The Pregnant Women’s Hospital is much more sophisticated. No need to stand in line. You can get a number from a machine, like the old “take a number” in the delicatessen. There are chairs in the blood test room, probably 50. There are, of course, a couple of hundred women waiting for blood tests at any one time, so the chairs are guarded like money. The result is that instead of standing in line, women are standing – not in line, but sort of milling around. More sophisticated. Feels less … socialist. First come, first served. Logistics people call it a FIFO inventory system – first in, first out. All stored inventory is the same. No special treatment, regardless.

Since some of the blood tests are needed, immediately, there is great pressure to get the test done. The technicians swab a little alcohol, plunge in the needle, remove what they need based on the paper given to them by the patient, stick on a label, wipe off the counter, and process the next victim.

There are hundreds of blood test samples being routed to testing every hour, with a fair amount of human handling in between. No chance for error here, right? No one puts the wrong label on a tube, or reads the wrong instructions for the test, or types the wrong results in the computer? It is China, you know, where everyone is very precise, down to the 5 yuan. I am pretty sure that the official medical statistics, at least, do not mention any missteps in the blood test confusion.

There is another room, to get weighed. Now this is not a precision “test,” even in the US. The doctor does not really need to do the weighing, and in China, the doctor does not. You do this, yourself, along with blood pressure test and temperature taking. You can write down the results, or remember them. The doctor will take your word for it. After all, you are the patient, and you should take some responsibility for your health care.

The temperature taking is easy. You don’t need to worry about cleanliness of thermometers or ear probes. The hospital doesn’t have any. You bring your own thermometer. If it is dirty, that is your problem. Personal responsibility.

I am not sure how to game the temperature system – if I needed my temperature taken, not sure if I would want to estimate high or low. After all, the temperature is measured in Celcius, not Fahrenheit, with only 100 gradations between freezing and boiling of water, instead of 212. That means that a difference of 1 degree does mean more here than it does in the US. Do I want to tell the doctor my temperature is 37 degrees or 38 degrees on the relatively unclear thermometer? That one degree has meaning here. It is the difference between 98.6 and 100.7. My answer hinges on whether I think it is better to go home untreated or stay and be treated at the hospital. Which would be better for my health? Personal responsibility, again.

Perhaps everyone’s fondest memories of pregnancy are getting the ultrasound. It is a time for a minor amount of personal attention, and you get to see what it is that is making all the fuss and the kicking, and start developing a connection. A little personal time – mom, dad, baby.

As in the US, the ultrasound exam is done in a little room, with the technician but only with the mom. The exam is five to ten minutes, maybe a bit less than in the US, but ok. The process is really special, and memorable for every pregnant mom. This is what the process is like.

The ultrasound testing office opens about 8:30. As you recall, for the blood tests, everyone gets a “take a number” ticket from a machine, and comes back when the big display shows that their number is coming up. That is for blood tests.

It would be possible to do that for the ultrasounds, but that must be too simple an idea. There is something more complicated going on that I must not be able to see with my western eyes.

So pregnant women, and their moms or husbands, start lining up about 6:00 in the morning to “get a number” from the woman behind the desk in the ultrasound office. By 8:30 there are – every day – two hundred or so women, each with their two or three attendants, in line around the entire mezzanine second floor. We might have been waiting to go in for our interview on Ellis Island. People propped against walls, lying down, carrying bags of lunch and maybe blankets and ubiquitous water bottles. Three, six, nine months pregnant. Again, there are a few chairs, but … This is the office designed to do ultrasounds. With – presumably – some consideration of demand in mind.

Understand, the pregnant women are not in line to get an ultrasound. They are in line to get a number that schedules the ultrasound. As with every other department, the ultrasound office closes for lunch. Some people who arrive late to stand in line – 7:30, say, an hour before the office opens – get a number for the afternoon, maybe 3:30. There are only so many ultrasounds that can be done in one day. There are no appointments. People standing too far back in line do not get a number, after standing in line for an hour or so, maybe traveling a long way by bus to get here. They don’t get a number for tomorrow. They come back, and stand in line tomorrow. This does great things for efficiency, particularly if the husband steals a day off from work to make the trip with his wife.

If you get a number for 3:30 in the afternoon, then, you count your lucky stars. You can now relax for six hours or so, until your ultrasound number comes up. This is such a special time for all moms. More grinding.

What is being optimized? Cannot tell. But the hospital designers certainly had ultrasounds in mind at the time of design. The hospital is not that old. The first principles of design are to consider end users in design – how many bathrooms, how many elevators of what size, what size offices for how many doctors … maybe even how many pregnant women might be standing in line to get a number at 6:00 AM. This is just supply and demand for architects. Chinese design, in every hospital I have been to, and that is about eight, fails miserably in consideration of demand.

I probably don’t need to tell you that the ultrasound, rather than the sort of quiet personal time with your baby-to-be-born that we know in the west, is a chaotic mess of a time. No doctor and mom looking at the head, and heart, and fingers. No warm exchange of hopes for the future and love for the child to be born. Processing people through the system is the goal. People do not matter. The System matters.

A key difference with the west, certainly the US, is that husbands are not allowed in the ultrasound room. Mystery must be maintained. Husbands are not allowed due to the Chinese one-child policy. As you know, China has had a one-child policy, in variations, since before 1980. The desire for a male child has led to millions of abortions of female fetuses. To combat that, hospitals and their workers are instructed to not reveal the sex of a fetus. A female might be aborted, particularly if the father learns that the fruit of his sperm is female. Having the husband in the ultrasound room, able to look at the ultrasound screen, might be able to see the tell-tale signs of a male – or not. In any case, families are usually not able to plan for a boy, or a girl, by buying clothes and toys and other things in advance. Mystery is preserved, until the time that the State releases its control of information.

You might get the idea that in the mass of confusion in any hallway of the hospital – women in a line completely around the mezzanine floor for ultrasounds, and to see the doctor, and get blood tests, and running (as it were) up and down the escalator to pay fees and correct mistakes, and go to the bathroom, and weigh themselves, and try to get something to eat after the blood test, and sleeping, and women about to give birth, and women having just given birth being wheeled through the traffic – in this chaos – that the hospital might be tempted to skimp on cleaning. That would be wrong, sort of.

Cleaning, or at least the physical manifestations of cleaning, are going on all the time. Cleaning ladies are sweeping people out of their way with mops and brooms, and moving cleaning buckets through the hallways. This work could be done at lunch, when everyone else disappears, or in the evening, but I think that would not convey the sense of cleaning that is key. It is the appearance that is important, not the result. And it contributes to the sense of chaos, and urgency, which is key to the grinding. How can we pay attention to you, when we have all This going on around us? Battlefield conditions.

When we got the amniocentesis test – which was strongly discouraged by the doctor – Qing was asked to lie on a small hospital bed for about half an hour before going home. During that time, a nurse came by to take blood pressure, and do a minor ultrasound, and everything was kept clean and sanitary throughout the procedure. Except that right adjacent to the nurse doing our ultrasound was a cleaning lady, with a rag that looked like one of my old shirts, wiping down all the surfaces on the table where the instruments were. The cleaning lady did not spit on the floor, or blow her nose into the rag, but I doubt that would have worsened the sanitary conditions. But when mystery is key, and power is maintained, then form over substance becomes a virtue. Like Fernando Lama, a la Billy Crystal, it is more important to look good than to feel good.

I think military people will say that even in battlefield conditions, it is possible to get excellent care in battlefield hospitals. Doctors answer questions, as best they can. No doubt they try to give the wounded some hope for recovery, as seems reasonable.

But one of the most surprising things about medical care in China is the honesty of doctors. This is translated as their willingness to say, in response to the simplest question about diagnosis, or prognosis, “I don’t know.” In the US, occasional use of this phrase might be interpreted as thoughtful and careful. Pretty regular use would be interpreted as stupid. But one hears that phrase over and over again, from doctors in China. I prefer to think that the doctors here are not stupid, so I am rooting for honesty. Maybe not well trained, maybe lazy, maybe just extraordinarily careful with what they say, but not stupid. “I don’t know” is the answer to give in China when you want to cut off further discussion. To ask a follow up question, like, for example, “Why the hell don’t you know?” would be impertinent. The cut-off-discussion answer to, “Why” is often the curt and dismissive, “No why.”

So, after one of our blood tests, the doctor saw that one of the blood sugar levels was high. The doctor told Qing that she had pregnancy-related diabetes. This can be a pretty serious matter, health for mother and baby. The doctor prescribed a series of blood tests, three per day for three days, and all to be done two hours after eating, so roughly 11:00 in the morning, 3:00 in the afternoon, and about 9:00 at night. Go to the hospital three times a day. Pain in the ass.

Qing had had blood tests before. No blood sugar problems were noted. She had eaten before this blood test, which was ok in this case, but had a lot of stress in getting to the hospital on buses and waiting in line (I was in Chicago at the time). The doctor did not have time, I suppose, to consider those factors. So, a series of blood tests occupying the whole day for three days, plus the worry that goes along with blood sugar problems being passed on to the baby. Looking up “pregnancy related diabetes” online, reading about possible severe consequences.

No one considered that there is absolutely nothing in Qing’s history to suggest a blood sugar level problem. She eats nutritious food, not too much by any means. No weight problem. She eats almost no sugar. Previous blood tests were normal. The day of the abnormal blood test, the stress of the day was abnormal (stress can trigger a high blood sugar level, as does eating). And the abnormal result was only a little bit abnormal. If the doctor had five minutes to ask a question, or consider the case, ask what Qing had for breakfast, or, maybe, physically look at Qing, she might have had another idea. But no one thought about this.

We got two days of the blood tests, at 11, 3, and 9. Don’t ask about logistics of getting them. All results came back normal. Went back to the doctor in about a week, brought the blood test results (you maintain your own medical records in China. Doctors and hospitals don’t do that. Again, personal responsibility for medical care). Doctor said everything looked fine, and Qing did not have diabetes. What could have caused the one abnormal test? “I don’t know.” Other than what she ate that morning, or the timing of the test after eating, or extra stress. An erroneous test result, perhaps? The doctor obviously did not have time to look it up on Wikipedia.

By the way, our doctor came to us via some excellent guanxi. Many women with excellent connections were also vying with us in the lines.

So if looking for optimization in health care, we are back to mystery. Some system, some procedural value, could be optimized, but I can’t see it myself. Not the doctor’s time, not the efficiency of the fee collection, not the minimizing of medical error. Not the time or care of the patients. It is quite clear, from all hospital experience, that people’s time has no value in this system. The procedural system might be maximizing the number of jobs, but there are too many things that get done by machine that could be done by people, if desired, and one does not get the overstaffed-and-underworked sense of employees in hospitals that one gets in some other systems in China.

And perhaps my western mind just doesn’t see what is going on. It often seems that Chinese are playing a different game, a bigger game, than we are used to confronting. So maybe system design is not about maximization, but about conservation. Perhaps system design is not optimizing anyone’s interests, even those of long-gone bureaucrats. Perhaps optimization is not now, and never has been, the goal. The goal, perhaps, is something bigger. What is the takeaway from the incidents of confusing building layout, process preservation, paperwork adoration, standing in line for hours, inability to schedule appointments, inability to check a result with a phone call or an email, and inability to ask questions?

What clearly is being conserved is the grinding. The grinding down of personality, of rage at stupidity, of the sense that things should work better. It is the poverty of imagination. The system is conserved. Maslow is right – self preservation is always the first and foremost priority. Hospitals in China never go out of business, and clearly don’t compete. The system grinds slowly, but it grinds exceedingly fine. The system truly is god-like.

Ju ra Trip Advisor – Restaurants Hangzhou

Ju ra Trip Advisor – Restaurants Hangzhou Chen dongfan, the author, and Brenna, my daughter – May, 2011

Chen dongfan, the author, and Brenna, my daughter – May, 2011

You can see more of Chen’ work at –

You can see more of Chen’ work at –

Source: Gilles Sabrié, The New York Times at

Source: Gilles Sabrié, The New York Times at

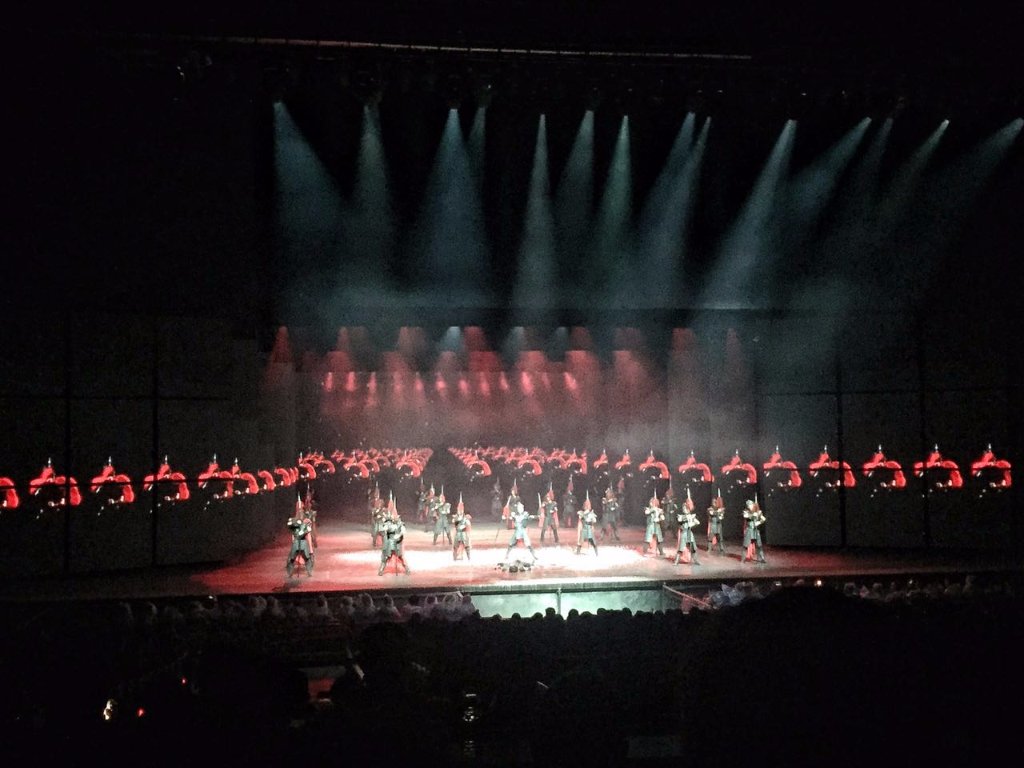

Performative Declamation

people talking without speaking …

note: I am reminded that this needs more than a little editing and a bit of shortening. Ok. You may skim rather than read. And I am now reminded of how GOP apparatchiks fall into line when defending the latest from their current dear leader. Another way in which the GOP has bought the Chinese export.

At Gettysburg, the featured speaker Edward Everett talked for two hours, and Lincoln for three minutes. Some thought Lincoln’s remarks were foolish and inappropriate. Chinese leaders never want to look foolish. I have sat through the one and two hour speeches that might have been delivered in ten minutes – if content were what mattered, rather than performance.

Over the course of fifteen years, my Chinese government students asked many questions about American governance or politics or economic policy. I occasionally wondered what happened when I began to explain details and found the attention of my Chinese questioners drifting off after only a moment’s discourse. Was it just poor delivery on my part? Maybe. Maybe not.

A response draped in correlative thinking would sometimes have been better. “Why do Americans have so many guns?” “A man’s home is his castle.” Less clear, no details, vague, but certainly – shorter and with some shred of correlation between guns and property rights.

Sometimes being shorter in public speaking is not enough. In public speaking in China, one needs to obfuscate, and if one is a leader, one needs to speak at length as a show of authority and sophistication. As in teaching in China, quantity is often a substitute for quality.

The joke about socialism – the only thing wrong with socialism is, too many meetings. Americans in universities and business and government complain about too many meetings, and too long, and too disconnected. But Americans are novices at meetings, compared with Chinese. Americans would not meet at all for many of the things that Chinese faculty in universities spend two or three hours on. A single phone call, perhaps a conference call, perhaps a momentary meeting in the hall. Perhaps a decision by the dean, or a proposal with alternatives, a sort of survey. In Chinese meetings, not always but often, every person at the meeting is expected to offer thoughts. And those thoughts are still constrained by deference to leaders. Chinese will sometimes refer to this as a form of democracy. The spoken word results are what is called performative declamation.

It is of no matter to a speaker at a meeting, or people on the dais, that perhaps no one in the audience is paying attention. Attendance may be mandatory; attention is not, when a single speaker can declaim for two or three hours. I was surprised to find leaders, who are given great deference in other circumstances, speaking to a crowd that has their heads down, focused on cell phones. But – performative is what counts. Substance will be communicated via other means.

One should immediately see the connections to use of political rhetoric in China. Speaking carefully to leaders is another aspect of Chineseness that is thousands of years old. The proper address, the proper kowtow, the proper words are more important than substance.

China has done an excellent job of adopting and adapting to western science and technology, and even to popular culture. The most senior and highest ranking CCP members are as global in their outlooks – probably more so – than most US Congressman. And yet, there remains one doppelganger, one elephant in the room, for the CCP in adapting to western ideas. That is the fear of multiple definitions of the good in society – that CCP will be unable to continue its legitimate monopoly on what counts for the Good in society. That way public dissension lies, civil society lies, multiple parties lie, and an end to the vanguard of the proletariat. Most frightening for the CCP, there is the constant assault from the west of attitudes to multiple goods in society – that the government does not always know the best path, that government does not always have the truth.

Individual people know this, and they know that the government does not tolerate too much dissent. Superficial disagreement about means and methods is fine; but disagreement with leaders about fundamental goals is dangerous in situations where the Party’s face, or prestige, is on the line.

There is not so much risk in university faculty meetings. But disagreement with the leader is still considered inappropriate, unless couched in vague terms. And there is pressure to follow the leader’s path.

In the US, we also understand “positive energy” in communications. Corporations and governments in the US want employees to project a positive image, and speak well of the company or the department and its work. “Tomorrow, we will do better – we will be better.” The CCP takes the positive energy message quite seriously. High school and university faculty and students are exhorted to use positive energy is speeches and writing.

One sees this in “performative declamation” 表态. Katherine Morton, at the Australian National University, describes the performance among Chinese students at a summer program in Turin, Italy. She was discussing the concept of the Chinese Dream, recently made popular by Xi Jinping –

Mainland Chinese participants, although of varied backgrounds and very different personal opinions (in private) felt that, after one of their number requested that she be given time to make a ‘personal’ statement on the subject of The China Dream, they all had to fall in line publicly and, hands raised, chorused a series of anodyne and vacuous declarations. If nothing else, I remarked to the non-Mainland students present, they had an insight into the Communist-inculcated cultural practice of ‘performative declamation’ 表态, a form of verbal posturing, an example of ‘group think’ aimed at presenting a united front in the face of independent thinking. It’s just this kind of knee-jerk solidarity that also vouchsafes the individual against the ever-present threat of being reported to the authorities back home.

Morton refers to this as the“Hall of the Unified Voice,”of the high Maoist era, in which each speaker declaims, for as long as thought expected, on the wisdom and wonderfulness of leaders and their plans.

Katherine Morton. The Rights and Responsibilities of Disagreement. The China Story, The Australian Centre on China in the World, September 21, 2014. Rights and Responsibilities of Disagreement

Ci Jiwei, author of Moral China in the Age of Reform, calls this form of speech surface optimism.

I call it surface optimism in the sense that it is not informed by an underlying quest for certainty as the hallmark of knowledge. As the trajectory of the Socratic tradition has repeatedly shown, the quest for certainty goes hand in hand with skepticism and has a uniquely powerful potential to lead to pessimistic conclusions about knowledge or at the very least to deflate overly confident claims regarding its possibility or scope.

Ci, Jiwei. What is in the cloud? A critical engagement with Thomas Metzger on “The clash between Chinese and western political theories” Boundary 2, 2007, v. 34 n. 3, p. 61-86. University of Hong Kong. At Ci Jiwei – What is in the Cloud?

Geremie Barme, editor at China Heritage Quarterly, at Australian National University, reminds us of “New China Newspeak,” a style of speaking and writing that is seen in official reports, speeches, and communications both within China and meant for foreign consumption.

The expression covers a wide range of prose and spoken forms of modern Chinese that have evolved and been consciously developed as the result of profound linguistic changes and experiments that date back to the late-Qing period, all of which are intimately connected with politics, ideas and the projection of power. Some of these styles reflect the militarization of Chinese in modern times (during the Republic, in Manchukuo, and under both the Nationalist and the Communist parties). Added to this is the stilted diction of bureaucratese (developed on the basis of traditional bureaucratic language), as well as scientific and academic jargon, to which have been added various forms of political and commercial exaggeration, euphemisms and neologisms. It mixes argot and the vernacular with the wooden language of Communist Party discourse. In recent decades this body of language practices has been ‘enriched’ by the verbiage of neoliberal economics and revived Cultural Revolution-era vituperation.

Geremie Barme. New China Newspeak. The China Story. Australian Centre on China in the World. August 2, 2012. Geremie Barme – New China Newspeak

Examples are to be found in any speech or any writing delivered by any leader at any level. Here is Jiang Shigong, eminent legal scholar at Peking University Law School, heaping praise on the “core leader, the core of the entire party,” Xi Jinping, on Xi’s speech at the 19th Party Congress in Otober, 2017 –

More important is the fact that Xi Jinping, at a particular moment in history, courageously took up the political responsibility of the historical mission, and in the face of an era of historical transformation of the entire world, demonstrated the capacity to construct the great theory facilitating China’s development path, as well as the capacity to control complicated domestic and international events, thus consolidating the hearts and minds of the entire Party and the people of the entire country, hence becoming the core leader praised by the entire Party, the entire army and the entire country, possessing a special ‘charismatic power’.

Gloria Davies. Post of Jiang Shigong, Philosophy and History: Interpreting the “Xi Jinping Era” through Xi’s Report to the Nineteenth National Congress of the CCP. Translation by David Ownby. Reading and Writing the China Dream.’ The China Story – Australian Centre on China in the World. Posted May 11, 2018. First published in Guangzhou Journal, January, 2018. Available at Interpreting Xi at the 19th Party Congress

This work by Jiang is considered good writing. Jiang has no problem emphasizing that Xi, and the CCP, speak for all Chinese on all matters of … well, not faith and morals, as does the Pope, but all matters of political and moral and economic and historical and cultural significance to all Chinese people. Nor does Jiang have any problem emphasizing how CCP delivered the Chinese people from centuries of oppression by the west, and will remain on guard against the evil influence of the west.

The dead hand of such writing can carry on for ten or twenty or thirty pages of single spaced, small font characters. You can imagine how it sounds when you have to listen for an hour or two or three.

Parenthetically, there is no question but that much of this writing is backed by extensive and detailed research in Chinese and western sources when the speech is delivered by a sufficiently high level official. Study is always a part of performative writing. No doubt Mr. Jiang could carry on a discussion of the philosophy of western or American law that would surprise some American legal scholars.

This stilted style is not unknown elsewhere, of course; and George Orwell provided a model in 1948 so insightful that one sometimes wonders if some CCP communications are not trying to simply model Orwell. Read Qiushi – the publication of the CCP Central Committee, Seeking Truth – if you want good examples. It is available in English at Qiushi – Seeking Truth.

Barme cites the term “socialist market economy” as a good example of newspeak. The term is confusing in the west; but in China, it expresses the contradictions of economic realities now. And, more important, it provides cover for whatever deviations from Marxism-Leninism the CCP wishes to undertake. A term with no meaning can mean anything; or, more precisely, it can mean whatever the government wants, whenever it wants it. CCP tells us that, as a Communist Party, it will decide the meaning of socialism. Well, ok, fair enough. But that privilege should not apply to all words. We have to remember Orwell in 1984 – War is Peace, Freedom is Slavery, Ignorance is Strength – that is the nature of what we are dealing with.

Qiushi (Seeking Truth). Publication of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, online in English at http://english.qstheory.cn/

But this “Mao-speak” is not a new concept within China. Barme notes that Confucius used particular individuals as character-models to either praise or censure political acts in moral terms in his comments on the state of Lu in the Spring and Autumn Annals. Confucius particularly called out for criticism those individuals – we might call them sophists – who could argue any side of a position. “Rectification of names” was about calling things by their proper name.

Barme’s comments on New China Newspeak remind us of Orwell, of course, in 1984 –

To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, to hold simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it, to believe that democracy was impossible and that the Party was the guardian of democracy, to forget, whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again, and above all, to apply the same process to the process itself—that was the ultimate subtlety; consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed. Even to understand the word ‘doublethink’ involved the use of doublethink.

George Orwell. 1984. Signet Classic, 1961, Book 1, Chapter 3, page 32.

Barme provides an example that reminds me of many private conversations with CCP members on politics or rights. One ends up quickly at a non sequiter – there is just nowhere to go short of an hour or two of discussion. I think that is what is intended. Barme’s example is about Liu Xiaobo, who later won the Nobel Prize in Literature –

On 11 February 2010, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Ma Zhaoxu 马朝旭 declared that: ‘There are no dissidents in China.’ This was, as Agence France-Presse reported it, ‘just hours after a Beijing court upheld an 11-year jail term for one of the country’s top pro-democracy voices.’ The report went on to say that: ‘Ma made the comment in answer to a question about leading mainland dissident Liu Xiaobo, whose appeal of his conviction on subversion charges was denied early on Thursday. When asked to elaborate, Ma said: “In China, you can judge yourself whether such a group exists. But I believe this term is questionable in China.”

Shortly thereafter, the artist and cultural blogger Ai Weiwei observed of this risible statement via his Twitter feed that:

1. Dissidents are criminals

2. Only criminals have dissenting views

3. The distinction between criminals and non-criminals is whether they have dissenting views

4. If you think China has dissidents, you are a criminal

5. The reason [China] has no dissidents is because they are [in fact already] criminals

6. Does anyone have a dissenting view regarding my statement?

Geramie Barme. Citing ‘There are no dissidents in China’, Agence France-Presse, 11 February 2010. Barme – Ai Weiwei on No Dissidents in China

One of the benefits of performative declamation is that one retains relative anonymity in the crowd. David Ze reminds us that in imperial China, one could not separate words from the person. What a person said indicated his personality. Depending on the Emperor, there was no trying out of ideas, or hypothetical suggestions. It seems not so different, now. David Ze –

This feature was distinct in imperial Chinese culture. If a suggestion was not favoured by the emperor, it meant the suggester’s loyalty should be questioned. In Hanfeizi’s words, it was not important what a person knew, but what, when, and how he said or refused to say it.

This feature… (was) maintained and developed in China long after writing and printing technologies were established. While many gifted men were jailed or killed for what they wrote and many literary works were lost because of the political persecution of their authors, these two features were substantially used for ideological control by the state in two ways. First, they were used as a strategy to eliminate political enemies and consolidate the centralized control of thought. Second, by propagating this mentality, the state mobilized the masses in its political campaigns against unorthodox views and the persons who held such views. When either the views or the persons were labelled “evil,” the masses would take their own initiative in resisting the “evil” influence by supervising and reporting the persons’ actions or by refusing to print, sell, and read their literature.

David Ze. Walter Ong’s Paradigm and Chinese Literacy. Canadian Journal of Communications, 20:4 (1995) Available at Ze – Walter Ong and Chinese Literacy

Lest one think this was only an imperial China concept, we have plenty of current examples. Violations of the requirements of performative declamation – what we might call free speech – can garnering instant rebuke from Chinese students, as well as from the government directly. One example, of many one can find. In 2017, Yang Shuping, a Chinese student studying at the University of Maryland, delivered a valedictory speech that made the mistake of expressing admiration and warmth for her time in the US, and comparing the US favorably to the conditions back home in Yunnan. She was immediately set upon by some of her fellow Chinese students, and she earned a direct rebuke from the government as well. Both Global Times and People’s Daily rebuked her expression of opinion.

See discussion at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shuping_Yang_commencement_speech_controversy

A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman (!) criticized Yang, saying, “Every Chinese citizen should be responsible for his or her remarks.” Responsible to whom? One should remember that the verb “to criticize” has different connotations in English and Chinese. To criticize someone in Chinese has a moral and normative tone – not, “that’s not a good idea,” but “you must not do that.” One wonders what lack of positive energy Ms. Yang will experience from businesses in her job hunt in China. Later, she did apologize to the Chinese people. No doubt, all 1.4 billion people breathed a sign of relief. But her violation will certainly be noted in her dang’an – her dossier that travels with her through life – for any employer to see.

Zhu Mei. MOFA responds to Chinese student’s controversial speech praising US. China Global Television Network (CGTN), 2017-05-24. Available at Ministry of Foreign Affairs responds to a student comment

This, of course, demonstrates the intense and intrusive behavior of Chinese foreign affairs departments, charged with fostering and sometimes enforcing politically correct speech among Chinese outside of China. Faced with isolation and being unemployable when she returned home, the girl felt forced to apologize to her classmates, the government, and presumably to the Chinese people, for ‘having hurt their feelings.’ The Chinese government departments charged with observing and guiding and monitoring speech of students outside China are sometimes referred to as the “Bureau of Overseas Chinese Affairs,” or “Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries” and are described as existing to keep overseas Chinese aware of what is happening in China, as if students were pining for information about Chinese baseball scores or what is on sale back home at the mall. These bureaus are being given a lot of attention as of 2018, as Chinese in overseas universities are perceived as not just students but sometimes as agents of the government. Quite a few of our Chinese government students in Chicago worked at such departments in Zhejiang or Liaoning provinces. In the Yang Shuping case, the “university’s Chinese Students and Scholars Association asked other mainland students studying in the US to create videos supporting and introducing their home towns. Those who do are encouraged to use the tagline “I have different views from Shuping Yang. I am proud of China.”” The Chinese Students and Scholars Association is supported by the Chinese government, in the form of monetary grants from local consulates.

Read more: Yang Shuping, sensing a threat, apologizes

There are multiple instances of Chinese with permanent residency in the US being told by the Chinese government that their family in China – parents, siblings, grandparents – might be harmed unless information is provided to assist the government in China. This despicable threat seems to apply mostly to Chinese wanted with regard to having smuggled money out of China, or Chinese with a sibling who knows too much about internal CCP operations. Obviously, the Chinese consulates in the US would be the logical agents to follow up on Chinese in the US. But the consulate can remain above the fray. The Bureau of Overseas Chinese Affairs is the agency that takes on this responsibility.

Leaders, and others, take active notice of the quality and quantity of deference to superiors. In 2017, there was much jockeying about who was going to be elevated to the Political Bureau Standing Committee (PSC), the group of seven most important Chinese leaders. Xi Jinping was expected to be making most of the choices himself, or at least have an extremely strong vote in selections. Journalists and politicians read or listened to speeches by likely candidates. No one actually “runs” for this position – that was part of the Bo Xilai hubris. Since Xi Jinping had been designated as the “core” of Chinese leadership, observers would count how many times Mr. Xi, or the core, were mentioned in speeches. More references indicated more deference, and possibly more chance to be elevated. Performance, indeed.

Confucius told us about artful speech, which he derided just as Aristotle derided sophists. Consider the “rectification of names,” passage in Analects 13 –

Tsze-lu said, “The ruler of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?”

The Master replied, “What is necessary is to rectify names.” “So! indeed!” said Tsze-lu. “You are wide of the mark! Why must there be such rectification?”

Confucius, responding –

“If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.

“When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do not flourish. When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded. When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot.

“Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect.”

Confucius is citing the need to speak the truth. But in the hands of the CCP, rectification of names means not speaking unless one is directed to speak, and then speaking as expected, not as one thinks. This is the performance game that Ci Jiwei described in the prior section.

Artistry with meaning is not a new concept. Ci Jiwei says this artistry with meaning creates the “two faces” problem in China.

People live in two worlds, then, an internal and external world. In the external world, people mimic theb truth and meanings provided to them, adherence to which is critical for continued employment and promotions if in government, state owned businesses, or academic world. People go through motions of assent. The internal world of belief and meaning is starved, however. As Ci says, the result is a vacuum of belief and meaning.

Ci Jiwei, Moral China in the Age of Reform, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

The “two worlds” apply to academic work, as well as politics. The French sinologist Henri Maspero, in a citation now lost, showed the gulf between Chinese and western historians in making sense of the past –

Where we look for facts, nothing but facts, a Chinese literatus looks for a rule of life, a moral. Seen from this perspective, history is not about the past but about the present, it is not science but literature, it is not about true and false but about right and wrong. It is all about judgments. And yes, it is history, not despite but because of all this: not an anemic and meaningless “realistic” reconstruction of the past but an interpretation of the past in terms of the present, intended to serve as a guide for the future.

It is this Chinese search for the convenient fact, in fact, that fosters western uncertainty with regard to findings of Xia and Shang dynasty relics. Certainty in archeology is generally rare. Why are you so sure, other than convenience, that this site you are researching is a Xia Dynasty site?

Performative declamation is part of the manner in which Chinese government addresses foreign leaders and governments. One should remember that zhongguo is considered the most civilized place on earth, the central country, the superior model. All other countries are vassal states, whether they provide tribute or not, as was expected for two thousand years, from the Xiongnu on to Tibet and Mongolia and Laos and Nepal, at the end of the Qing. China accepts homage when it works to the benefit of China, but considers itself under no obligation to respond in kind. So the Chinese government has no qualms about instructing the barbarians, even now, in proper deference to China and the Chinese people. This is performative declamation in foreign policy jargon. Tianxia, all under heaven, is properly ruled by the emperor in Beijing, even in the 21st century.

Performative declamation is not only for external communication. In the innumerable – and per CCP officials, seemingly endless – meetings to discuss elements of business, it is customary for every individual in the meeting to speak, to offer an opinion. But how to know what opinion to offer? Following the message of the leader is not unknown in American business meetings. But what if the big leader in the room has not arrived yet, or does not speak first? What to do?

Contrary to expectations, the big leader in the room in any meeting does not necessarily always speak first. The big leader could speak first, and indicate what course of action he wants to follow. Subordinates, all of whom get to speak as well, then know how to declaim. The big leader may leave, if he has other commitments; but the subordinates all remain to perform. All participants watch each other. If the big leader in the room speaks last, it will usually be clear from his assistant what path he wishes to follow, so subordinates will be able to perform well in any case. Lest you think I exaggerate on the requirement that subordinates exude praise and follow the leader, there is a term for this behavior toward the leader – pai ma pi, which means, patting the horse’s ass. Everyone in China knows this phrase.

Depending on the leader, some real discussion and disagreement may be permitted. This permission may be simply the habit of that particular leader, or the subject matter may indicate that real opinions are sought. But if the leader in the room is very powerful, then disagreement tends to disappear, as it might in meetings in the US. Disagreement brings loss of face, even for a powerful leader. Just as Hanfeizi said, if a proposal is not favored by the leader, then the suggester’s loyalty should be questioned. There is no such thing as loyal opposition or heeding the advice of the lone voice.

The constant sense of the need to struggle develops another form of anxiety in China, one that is seen in government, in the CCP, in business, in schools. That is the need to perform, immediately, upon demand. Urgency is a form of currency – ability to perform quickly for a particular leader is a show of respect, and gives face to that leader.

We understand urgency in the US – real deadlines and arbitrary demands by the boss. American urgency is usually for the sake of the task, not for the face of the boss, and therein lies a difference. China is different.

I was at dinner with three university colleagues, all PhDs at my school. One of the three was the vice dean of the business school, and the other two were senior faculty in that school. After dinner, about 9:00 PM, after drinking – some, not too much – we were driving back to school. Question from the driver to each – should we drop you at home or at the office? Answer – office, I must go back to finish important work. At night. After dinner. After drinks.

At the time, I was suitably impressed. Now, some years later, I understand that answer as a sort of performative declamation, an “I work harder than you do” expression. It was pointless – all three went home directly.

But the pressure to produce, to work harder than anyone else, indeed, to show off for the leader, is always present. It gives high performance a whole new meaning.