people talking without speaking …

note: I am reminded that this needs more than a little editing and a bit of shortening. Ok. You may skim rather than read. And I am now reminded of how GOP apparatchiks fall into line when defending the latest from their current dear leader. Another way in which the GOP has bought the Chinese export.

At Gettysburg, the featured speaker Edward Everett talked for two hours, and Lincoln for three minutes. Some thought Lincoln’s remarks were foolish and inappropriate. Chinese leaders never want to look foolish. I have sat through the one and two hour speeches that might have been delivered in ten minutes – if content were what mattered, rather than performance.

Over the course of fifteen years, my Chinese government students asked many questions about American governance or politics or economic policy. I occasionally wondered what happened when I began to explain details and found the attention of my Chinese questioners drifting off after only a moment’s discourse. Was it just poor delivery on my part? Maybe. Maybe not.

A response draped in correlative thinking would sometimes have been better. “Why do Americans have so many guns?” “A man’s home is his castle.” Less clear, no details, vague, but certainly – shorter and with some shred of correlation between guns and property rights.

Sometimes being shorter in public speaking is not enough. In public speaking in China, one needs to obfuscate, and if one is a leader, one needs to speak at length as a show of authority and sophistication. As in teaching in China, quantity is often a substitute for quality.

The joke about socialism – the only thing wrong with socialism is, too many meetings. Americans in universities and business and government complain about too many meetings, and too long, and too disconnected. But Americans are novices at meetings, compared with Chinese. Americans would not meet at all for many of the things that Chinese faculty in universities spend two or three hours on. A single phone call, perhaps a conference call, perhaps a momentary meeting in the hall. Perhaps a decision by the dean, or a proposal with alternatives, a sort of survey. In Chinese meetings, not always but often, every person at the meeting is expected to offer thoughts. And those thoughts are still constrained by deference to leaders. Chinese will sometimes refer to this as a form of democracy. The spoken word results are what is called performative declamation.

It is of no matter to a speaker at a meeting, or people on the dais, that perhaps no one in the audience is paying attention. Attendance may be mandatory; attention is not, when a single speaker can declaim for two or three hours. I was surprised to find leaders, who are given great deference in other circumstances, speaking to a crowd that has their heads down, focused on cell phones. But – performative is what counts. Substance will be communicated via other means.

One should immediately see the connections to use of political rhetoric in China. Speaking carefully to leaders is another aspect of Chineseness that is thousands of years old. The proper address, the proper kowtow, the proper words are more important than substance.

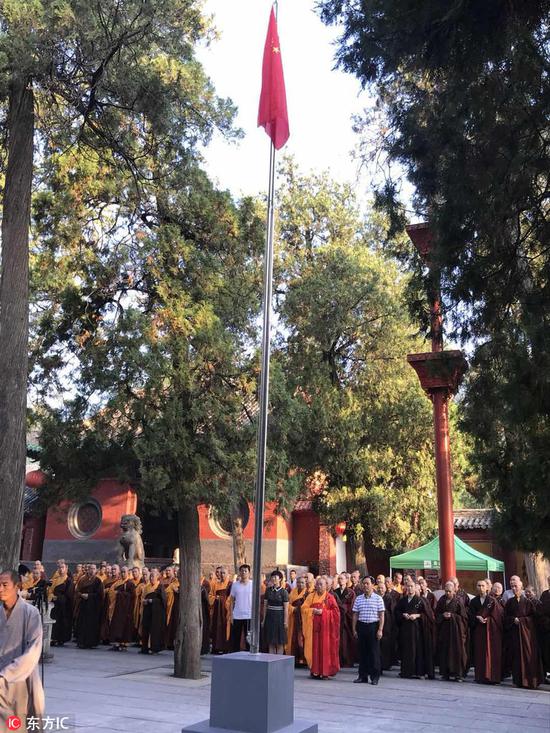

China has done an excellent job of adopting and adapting to western science and technology, and even to popular culture. The most senior and highest ranking CCP members are as global in their outlooks – probably more so – than most US Congressman. And yet, there remains one doppelganger, one elephant in the room, for the CCP in adapting to western ideas. That is the fear of multiple definitions of the good in society – that CCP will be unable to continue its legitimate monopoly on what counts for the Good in society. That way public dissension lies, civil society lies, multiple parties lie, and an end to the vanguard of the proletariat. Most frightening for the CCP, there is the constant assault from the west of attitudes to multiple goods in society – that the government does not always know the best path, that government does not always have the truth.

Individual people know this, and they know that the government does not tolerate too much dissent. Superficial disagreement about means and methods is fine; but disagreement with leaders about fundamental goals is dangerous in situations where the Party’s face, or prestige, is on the line.

There is not so much risk in university faculty meetings. But disagreement with the leader is still considered inappropriate, unless couched in vague terms. And there is pressure to follow the leader’s path.

In the US, we also understand “positive energy” in communications. Corporations and governments in the US want employees to project a positive image, and speak well of the company or the department and its work. “Tomorrow, we will do better – we will be better.” The CCP takes the positive energy message quite seriously. High school and university faculty and students are exhorted to use positive energy is speeches and writing.

One sees this in “performative declamation” 表态. Katherine Morton, at the Australian National University, describes the performance among Chinese students at a summer program in Turin, Italy. She was discussing the concept of the Chinese Dream, recently made popular by Xi Jinping –

Mainland Chinese participants, although of varied backgrounds and very different personal opinions (in private) felt that, after one of their number requested that she be given time to make a ‘personal’ statement on the subject of The China Dream, they all had to fall in line publicly and, hands raised, chorused a series of anodyne and vacuous declarations. If nothing else, I remarked to the non-Mainland students present, they had an insight into the Communist-inculcated cultural practice of ‘performative declamation’ 表态, a form of verbal posturing, an example of ‘group think’ aimed at presenting a united front in the face of independent thinking. It’s just this kind of knee-jerk solidarity that also vouchsafes the individual against the ever-present threat of being reported to the authorities back home.

Morton refers to this as the“Hall of the Unified Voice,”of the high Maoist era, in which each speaker declaims, for as long as thought expected, on the wisdom and wonderfulness of leaders and their plans.

Katherine Morton. The Rights and Responsibilities of Disagreement. The China Story, The Australian Centre on China in the World, September 21, 2014. Rights and Responsibilities of Disagreement

Ci Jiwei, author of Moral China in the Age of Reform, calls this form of speech surface optimism.

I call it surface optimism in the sense that it is not informed by an underlying quest for certainty as the hallmark of knowledge. As the trajectory of the Socratic tradition has repeatedly shown, the quest for certainty goes hand in hand with skepticism and has a uniquely powerful potential to lead to pessimistic conclusions about knowledge or at the very least to deflate overly confident claims regarding its possibility or scope.

Ci, Jiwei. What is in the cloud? A critical engagement with Thomas Metzger on “The clash between Chinese and western political theories” Boundary 2, 2007, v. 34 n. 3, p. 61-86. University of Hong Kong. At Ci Jiwei – What is in the Cloud?

Geremie Barme, editor at China Heritage Quarterly, at Australian National University, reminds us of “New China Newspeak,” a style of speaking and writing that is seen in official reports, speeches, and communications both within China and meant for foreign consumption.

The expression covers a wide range of prose and spoken forms of modern Chinese that have evolved and been consciously developed as the result of profound linguistic changes and experiments that date back to the late-Qing period, all of which are intimately connected with politics, ideas and the projection of power. Some of these styles reflect the militarization of Chinese in modern times (during the Republic, in Manchukuo, and under both the Nationalist and the Communist parties). Added to this is the stilted diction of bureaucratese (developed on the basis of traditional bureaucratic language), as well as scientific and academic jargon, to which have been added various forms of political and commercial exaggeration, euphemisms and neologisms. It mixes argot and the vernacular with the wooden language of Communist Party discourse. In recent decades this body of language practices has been ‘enriched’ by the verbiage of neoliberal economics and revived Cultural Revolution-era vituperation.

Geremie Barme. New China Newspeak. The China Story. Australian Centre on China in the World. August 2, 2012. Geremie Barme – New China Newspeak

Examples are to be found in any speech or any writing delivered by any leader at any level. Here is Jiang Shigong, eminent legal scholar at Peking University Law School, heaping praise on the “core leader, the core of the entire party,” Xi Jinping, on Xi’s speech at the 19th Party Congress in Otober, 2017 –

More important is the fact that Xi Jinping, at a particular moment in history, courageously took up the political responsibility of the historical mission, and in the face of an era of historical transformation of the entire world, demonstrated the capacity to construct the great theory facilitating China’s development path, as well as the capacity to control complicated domestic and international events, thus consolidating the hearts and minds of the entire Party and the people of the entire country, hence becoming the core leader praised by the entire Party, the entire army and the entire country, possessing a special ‘charismatic power’.

Gloria Davies. Post of Jiang Shigong, Philosophy and History: Interpreting the “Xi Jinping Era” through Xi’s Report to the Nineteenth National Congress of the CCP. Translation by David Ownby. Reading and Writing the China Dream.’ The China Story – Australian Centre on China in the World. Posted May 11, 2018. First published in Guangzhou Journal, January, 2018. Available at Interpreting Xi at the 19th Party Congress

This work by Jiang is considered good writing. Jiang has no problem emphasizing that Xi, and the CCP, speak for all Chinese on all matters of … well, not faith and morals, as does the Pope, but all matters of political and moral and economic and historical and cultural significance to all Chinese people. Nor does Jiang have any problem emphasizing how CCP delivered the Chinese people from centuries of oppression by the west, and will remain on guard against the evil influence of the west.

The dead hand of such writing can carry on for ten or twenty or thirty pages of single spaced, small font characters. You can imagine how it sounds when you have to listen for an hour or two or three.

Parenthetically, there is no question but that much of this writing is backed by extensive and detailed research in Chinese and western sources when the speech is delivered by a sufficiently high level official. Study is always a part of performative writing. No doubt Mr. Jiang could carry on a discussion of the philosophy of western or American law that would surprise some American legal scholars.

This stilted style is not unknown elsewhere, of course; and George Orwell provided a model in 1948 so insightful that one sometimes wonders if some CCP communications are not trying to simply model Orwell. Read Qiushi – the publication of the CCP Central Committee, Seeking Truth – if you want good examples. It is available in English at Qiushi – Seeking Truth.

Barme cites the term “socialist market economy” as a good example of newspeak. The term is confusing in the west; but in China, it expresses the contradictions of economic realities now. And, more important, it provides cover for whatever deviations from Marxism-Leninism the CCP wishes to undertake. A term with no meaning can mean anything; or, more precisely, it can mean whatever the government wants, whenever it wants it. CCP tells us that, as a Communist Party, it will decide the meaning of socialism. Well, ok, fair enough. But that privilege should not apply to all words. We have to remember Orwell in 1984 – War is Peace, Freedom is Slavery, Ignorance is Strength – that is the nature of what we are dealing with.

Qiushi (Seeking Truth). Publication of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, online in English at http://english.qstheory.cn/

But this “Mao-speak” is not a new concept within China. Barme notes that Confucius used particular individuals as character-models to either praise or censure political acts in moral terms in his comments on the state of Lu in the Spring and Autumn Annals. Confucius particularly called out for criticism those individuals – we might call them sophists – who could argue any side of a position. “Rectification of names” was about calling things by their proper name.

Barme’s comments on New China Newspeak remind us of Orwell, of course, in 1984 –

To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, to hold simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it, to believe that democracy was impossible and that the Party was the guardian of democracy, to forget, whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again, and above all, to apply the same process to the process itself—that was the ultimate subtlety; consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed. Even to understand the word ‘doublethink’ involved the use of doublethink.

George Orwell. 1984. Signet Classic, 1961, Book 1, Chapter 3, page 32.

Barme provides an example that reminds me of many private conversations with CCP members on politics or rights. One ends up quickly at a non sequiter – there is just nowhere to go short of an hour or two of discussion. I think that is what is intended. Barme’s example is about Liu Xiaobo, who later won the Nobel Prize in Literature –

On 11 February 2010, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Ma Zhaoxu 马朝旭 declared that: ‘There are no dissidents in China.’ This was, as Agence France-Presse reported it, ‘just hours after a Beijing court upheld an 11-year jail term for one of the country’s top pro-democracy voices.’ The report went on to say that: ‘Ma made the comment in answer to a question about leading mainland dissident Liu Xiaobo, whose appeal of his conviction on subversion charges was denied early on Thursday. When asked to elaborate, Ma said: “In China, you can judge yourself whether such a group exists. But I believe this term is questionable in China.”

Shortly thereafter, the artist and cultural blogger Ai Weiwei observed of this risible statement via his Twitter feed that:

1. Dissidents are criminals

2. Only criminals have dissenting views

3. The distinction between criminals and non-criminals is whether they have dissenting views

4. If you think China has dissidents, you are a criminal

5. The reason [China] has no dissidents is because they are [in fact already] criminals

6. Does anyone have a dissenting view regarding my statement?

Geramie Barme. Citing ‘There are no dissidents in China’, Agence France-Presse, 11 February 2010. Barme – Ai Weiwei on No Dissidents in China

One of the benefits of performative declamation is that one retains relative anonymity in the crowd. David Ze reminds us that in imperial China, one could not separate words from the person. What a person said indicated his personality. Depending on the Emperor, there was no trying out of ideas, or hypothetical suggestions. It seems not so different, now. David Ze –

This feature was distinct in imperial Chinese culture. If a suggestion was not favoured by the emperor, it meant the suggester’s loyalty should be questioned. In Hanfeizi’s words, it was not important what a person knew, but what, when, and how he said or refused to say it.

This feature… (was) maintained and developed in China long after writing and printing technologies were established. While many gifted men were jailed or killed for what they wrote and many literary works were lost because of the political persecution of their authors, these two features were substantially used for ideological control by the state in two ways. First, they were used as a strategy to eliminate political enemies and consolidate the centralized control of thought. Second, by propagating this mentality, the state mobilized the masses in its political campaigns against unorthodox views and the persons who held such views. When either the views or the persons were labelled “evil,” the masses would take their own initiative in resisting the “evil” influence by supervising and reporting the persons’ actions or by refusing to print, sell, and read their literature.

David Ze. Walter Ong’s Paradigm and Chinese Literacy. Canadian Journal of Communications, 20:4 (1995) Available at Ze – Walter Ong and Chinese Literacy

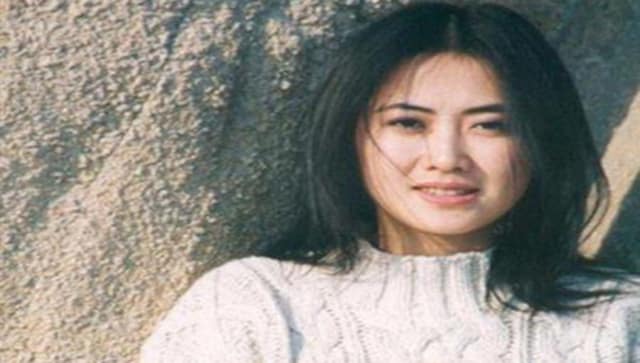

Lest one think this was only an imperial China concept, we have plenty of current examples. Violations of the requirements of performative declamation – what we might call free speech – can garnering instant rebuke from Chinese students, as well as from the government directly. One example, of many one can find. In 2017, Yang Shuping, a Chinese student studying at the University of Maryland, delivered a valedictory speech that made the mistake of expressing admiration and warmth for her time in the US, and comparing the US favorably to the conditions back home in Yunnan. She was immediately set upon by some of her fellow Chinese students, and she earned a direct rebuke from the government as well. Both Global Times and People’s Daily rebuked her expression of opinion.

See discussion at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shuping_Yang_commencement_speech_controversy

A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman (!) criticized Yang, saying, “Every Chinese citizen should be responsible for his or her remarks.” Responsible to whom? One should remember that the verb “to criticize” has different connotations in English and Chinese. To criticize someone in Chinese has a moral and normative tone – not, “that’s not a good idea,” but “you must not do that.” One wonders what lack of positive energy Ms. Yang will experience from businesses in her job hunt in China. Later, she did apologize to the Chinese people. No doubt, all 1.4 billion people breathed a sign of relief. But her violation will certainly be noted in her dang’an – her dossier that travels with her through life – for any employer to see.

Zhu Mei. MOFA responds to Chinese student’s controversial speech praising US. China Global Television Network (CGTN), 2017-05-24. Available at Ministry of Foreign Affairs responds to a student comment

This, of course, demonstrates the intense and intrusive behavior of Chinese foreign affairs departments, charged with fostering and sometimes enforcing politically correct speech among Chinese outside of China. Faced with isolation and being unemployable when she returned home, the girl felt forced to apologize to her classmates, the government, and presumably to the Chinese people, for ‘having hurt their feelings.’ The Chinese government departments charged with observing and guiding and monitoring speech of students outside China are sometimes referred to as the “Bureau of Overseas Chinese Affairs,” or “Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries” and are described as existing to keep overseas Chinese aware of what is happening in China, as if students were pining for information about Chinese baseball scores or what is on sale back home at the mall. These bureaus are being given a lot of attention as of 2018, as Chinese in overseas universities are perceived as not just students but sometimes as agents of the government. Quite a few of our Chinese government students in Chicago worked at such departments in Zhejiang or Liaoning provinces. In the Yang Shuping case, the “university’s Chinese Students and Scholars Association asked other mainland students studying in the US to create videos supporting and introducing their home towns. Those who do are encouraged to use the tagline “I have different views from Shuping Yang. I am proud of China.”” The Chinese Students and Scholars Association is supported by the Chinese government, in the form of monetary grants from local consulates.

Read more: Yang Shuping, sensing a threat, apologizes

There are multiple instances of Chinese with permanent residency in the US being told by the Chinese government that their family in China – parents, siblings, grandparents – might be harmed unless information is provided to assist the government in China. This despicable threat seems to apply mostly to Chinese wanted with regard to having smuggled money out of China, or Chinese with a sibling who knows too much about internal CCP operations. Obviously, the Chinese consulates in the US would be the logical agents to follow up on Chinese in the US. But the consulate can remain above the fray. The Bureau of Overseas Chinese Affairs is the agency that takes on this responsibility.

Leaders, and others, take active notice of the quality and quantity of deference to superiors. In 2017, there was much jockeying about who was going to be elevated to the Political Bureau Standing Committee (PSC), the group of seven most important Chinese leaders. Xi Jinping was expected to be making most of the choices himself, or at least have an extremely strong vote in selections. Journalists and politicians read or listened to speeches by likely candidates. No one actually “runs” for this position – that was part of the Bo Xilai hubris. Since Xi Jinping had been designated as the “core” of Chinese leadership, observers would count how many times Mr. Xi, or the core, were mentioned in speeches. More references indicated more deference, and possibly more chance to be elevated. Performance, indeed.

Confucius told us about artful speech, which he derided just as Aristotle derided sophists. Consider the “rectification of names,” passage in Analects 13 –

Tsze-lu said, “The ruler of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?”

The Master replied, “What is necessary is to rectify names.” “So! indeed!” said Tsze-lu. “You are wide of the mark! Why must there be such rectification?”

Confucius, responding –

“If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.

“When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do not flourish. When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded. When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot.

“Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect.”

Confucius is citing the need to speak the truth. But in the hands of the CCP, rectification of names means not speaking unless one is directed to speak, and then speaking as expected, not as one thinks. This is the performance game that Ci Jiwei described in the prior section.

Artistry with meaning is not a new concept. Ci Jiwei says this artistry with meaning creates the “two faces” problem in China.

People live in two worlds, then, an internal and external world. In the external world, people mimic theb truth and meanings provided to them, adherence to which is critical for continued employment and promotions if in government, state owned businesses, or academic world. People go through motions of assent. The internal world of belief and meaning is starved, however. As Ci says, the result is a vacuum of belief and meaning.

Ci Jiwei, Moral China in the Age of Reform, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

The “two worlds” apply to academic work, as well as politics. The French sinologist Henri Maspero, in a citation now lost, showed the gulf between Chinese and western historians in making sense of the past –

Where we look for facts, nothing but facts, a Chinese literatus looks for a rule of life, a moral. Seen from this perspective, history is not about the past but about the present, it is not science but literature, it is not about true and false but about right and wrong. It is all about judgments. And yes, it is history, not despite but because of all this: not an anemic and meaningless “realistic” reconstruction of the past but an interpretation of the past in terms of the present, intended to serve as a guide for the future.

It is this Chinese search for the convenient fact, in fact, that fosters western uncertainty with regard to findings of Xia and Shang dynasty relics. Certainty in archeology is generally rare. Why are you so sure, other than convenience, that this site you are researching is a Xia Dynasty site?

Performative declamation is part of the manner in which Chinese government addresses foreign leaders and governments. One should remember that zhongguo is considered the most civilized place on earth, the central country, the superior model. All other countries are vassal states, whether they provide tribute or not, as was expected for two thousand years, from the Xiongnu on to Tibet and Mongolia and Laos and Nepal, at the end of the Qing. China accepts homage when it works to the benefit of China, but considers itself under no obligation to respond in kind. So the Chinese government has no qualms about instructing the barbarians, even now, in proper deference to China and the Chinese people. This is performative declamation in foreign policy jargon. Tianxia, all under heaven, is properly ruled by the emperor in Beijing, even in the 21st century.

Performative declamation is not only for external communication. In the innumerable – and per CCP officials, seemingly endless – meetings to discuss elements of business, it is customary for every individual in the meeting to speak, to offer an opinion. But how to know what opinion to offer? Following the message of the leader is not unknown in American business meetings. But what if the big leader in the room has not arrived yet, or does not speak first? What to do?

Contrary to expectations, the big leader in the room in any meeting does not necessarily always speak first. The big leader could speak first, and indicate what course of action he wants to follow. Subordinates, all of whom get to speak as well, then know how to declaim. The big leader may leave, if he has other commitments; but the subordinates all remain to perform. All participants watch each other. If the big leader in the room speaks last, it will usually be clear from his assistant what path he wishes to follow, so subordinates will be able to perform well in any case. Lest you think I exaggerate on the requirement that subordinates exude praise and follow the leader, there is a term for this behavior toward the leader – pai ma pi, which means, patting the horse’s ass. Everyone in China knows this phrase.

Depending on the leader, some real discussion and disagreement may be permitted. This permission may be simply the habit of that particular leader, or the subject matter may indicate that real opinions are sought. But if the leader in the room is very powerful, then disagreement tends to disappear, as it might in meetings in the US. Disagreement brings loss of face, even for a powerful leader. Just as Hanfeizi said, if a proposal is not favored by the leader, then the suggester’s loyalty should be questioned. There is no such thing as loyal opposition or heeding the advice of the lone voice.

The constant sense of the need to struggle develops another form of anxiety in China, one that is seen in government, in the CCP, in business, in schools. That is the need to perform, immediately, upon demand. Urgency is a form of currency – ability to perform quickly for a particular leader is a show of respect, and gives face to that leader.

We understand urgency in the US – real deadlines and arbitrary demands by the boss. American urgency is usually for the sake of the task, not for the face of the boss, and therein lies a difference. China is different.

I was at dinner with three university colleagues, all PhDs at my school. One of the three was the vice dean of the business school, and the other two were senior faculty in that school. After dinner, about 9:00 PM, after drinking – some, not too much – we were driving back to school. Question from the driver to each – should we drop you at home or at the office? Answer – office, I must go back to finish important work. At night. After dinner. After drinks.

At the time, I was suitably impressed. Now, some years later, I understand that answer as a sort of performative declamation, an “I work harder than you do” expression. It was pointless – all three went home directly.

But the pressure to produce, to work harder than anyone else, indeed, to show off for the leader, is always present. It gives high performance a whole new meaning.

Source:

Source:

All photos:

All photos:

Let’s remember what we are dealing with …

News reporting is so uneven. No mass shooting in the US is censored information in China – in fact, the news is prominently featured. From China Xinhua News on Twitter –

China Xinhua News

@XHNews

Shootings this weekend at a Texas Walmart and a bar in Ohio have left 30 people dead. Retail employees are taking to social media to say they’re terrified to go to work. Workers fear getting shot at their workplace

The Chinese government twitter account has several posts on the shootings, with video.

At the same time, Xinhua completely missed this story –

Chinese rights lawyer Chen Jiangang flees to US to escape “persecution” in China

The South China Morning Post did report the story.

Chen is a human rights lawyer who has been threatened and harassment before. He was representing Huang Yang, daughter in law of disgraced leader Zhou Yongkang. Huang is an American citizen. She has not been allowed to leave China over what is termed a rental disagreement, but it is not uncommon to punish relatives of disgraced CCP leaders without evidence of any wrongdoing.

Huang explained that Wang Cun, deputy director of the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Justice, threatened Chen if he continued to represent her. Chen was told that he would disappear if he continued to represent his client.

Chen had been threatened before. In April of this year, he was not allowed to leave China for a fellowship funded by the US government, citing national security concerns.

In 2017, Chen’s entire family was put on an exit ban list, which has become a common means of targeting Chinese and foreigners who displease the government.

It is not clear how Chen and his family were able to get out. News reports say that they traveled through several countries before finally arriving in the US. China Aid, a non-profit reporting on human rights abuses in China, seems to have helped Chen and his family get out.

Lawyer Chen Jiangang (second from left) and his family have fled China for the United States Source: ChinaAid

China Aid, by the way, is a remarkable organization. It seeks to expose persecution, torture, and imprisonment of Christians and human rights lawyers in China.

Xinhua seems to have missed this story. Perhaps international news is more compelling in this case.