Links to Related Articles

Change Management 1/3

Change Management 2/3

Change Management 3/3

China has changed dramatically in the last forty years. Business writer and thought leader Bob Yovovich tells us that China urbanized in half the time it took the US and with ten times the number of relocations. Such rapid change must have induced complex interlocking social shifts and costs – customs broken, institutions abandoned, social ties destroyed. Now, wither China? Wither CCP?

Three questions in three posts. This is post #3.

Thesis #3 Will Mr. Democracy eventually overpower Mr. Science in Chinese culture? A democratic future must come with modernization

Below –

Evidence for the coming of Mr. Democracy

Antithesis #3 No evidence for democracy anytime soon

Trusting in leadership by the best

Democracy and capitalism united

Science is about a search for truth. It is logical and precise. But science – as reflected in logic and precision – can only take society so far. Democracies and freedoms are much more complex than science, but people need that complexity to live meaningful lives.

Democracies and freedoms come in many flavors. As much as CCP tries to keep China pure – free of western influence – that is really a losing proposition. Young Chinese returning from school abroad bring back ideas as well as technical skills. One cannot really separate ideas about science from ideas about freedom. The arc of history points toward freedom.

China is certainly capitalistic in some ways; so is the US. Both are socialist and corporatist in some ways as well. For decades American political scientists and politicians have put faith in the argument that once China has capitalism some form of democracy cannot be far behind. American China policy from the time of Clinton has been predicated on a path of opening up-GDP growth-capitalism-democracy.

Evidence for the coming of Mr. Democracy

Modernization theory has been a staple of foreign policy and international relations theory for more than fifty years. There are variations, but generally the concept is that because capitalism and democracy are intimately related, and both of them, along with science, are fundamentally searches for truth, then a country that values science and economic development will naturally evolve to having democratic features. Ipso facto.

The US was a model for Chinese democracy for a long time. The first quarter of the 20th century is when Mr. Science and Mr. Democracy became models, directly from lived experience of Chinese in the US.

No modern country can be autarkic or completely isolationist. North Korea is perhaps the closest approximation. And among the many flavors of democracy are democratic models in the Confucian societies of Japan and South Korea and Taiwan. Clearly Confucian precepts and east Asian heritage are no barrier to democracy. But perhaps the most appealing to both Chinese citizens and CCP is the government in Singapore. Singapore is sort of democratic – there is a very limited sort of voting – but government is squeaky clean along with the streets and freedom to walk around freely is everywhere. Crime is punished. Singapore rejects liberal democratic values, limits free speech and public participation in government without significant voting rights. The US is not an attractive model for China. But Singapore … perhaps.

Tu Weiming, a premier new Confucian scholar, says Confucian principles of benevolence and tolerance are best achieved in a democratic system. These ancient Chinese ideas are ideas about individual freedom. CCP will be overthrown, as has every dynasty for more than two thousand years.

Antithesis #3 No evidence for democracy anytime soon

One doesn’t get to write or say what one thinks in the civilization-state that is CCP, but mostly no one thinks about it. Businesses work for the state. CCP is the new dynasty, and they are looking out for the welfare of all CCP. Might be good to remember one of those Christian fundamentalist bumper stickers one sees – slightly modified. CCP reminds everyone that they are leading the people. “Xi said it. I believe it. That settles it.”

I wrote a bit about this four years ago Must China have Democracy or Die? The arguments against the modernization view are detailed and convincing. Suffice it to say that China does not have now, has never, and is unlikely any decade soon to have the prerequisites for democracy. Robert Dahl laid out seven or eight requirements in his 1972 Polyarchy.

Dahl’s requirements for a democracy –

- Have preferences weighted equally in conduct of government

- Freedom of expression

- Right to vote

- Eligibility for public office

- Right of political leaders to compete for support and votes

- Alternative sources of information

- Free and fair elections

- Institutions for making government policies depend on votes and other expressions of preference

We have learned that a functioning democracy has some form of civil society as a prerequisite. Civil society can propose alternatives to government policy, organize people in opposition to policy, sponsor think tanks and colloquia and free speech and free thinking. This cannot be tolerated by any communist regime. To allow for free speech and thinking is to promote disintegration of the Party.

Some other reasons for democracy not to evolve, from culture and demographics.

We saw thousands of people in the streets in Beijing and Shanghai in fall of 2022 protesting the zero-covid restrictions. This frightened Xi, and the bans on movement were removed. People then went back to work, back to school, back to shopping. Even though we saw the signs on the bridge in Beijing …

Source: Helen Davidson in Taipei and Verna Yu. Guardian at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/13/shanghai-covid-restrictions-fuel-fears-of-another-lockdown

“Go on strike at school and work, remove dictator and national traitor Xi Jinping! We want to eat, we want freedom, we want to vote!”

… there has been no follow-on. No residual of protests related to Xi, CCP, or the occupation of Chinese people by CCP.

Tanner Greer at The Scholar’s Stage lists reasons for Chinese elites, including college educated young Chinese, to keep their heads down and mouths closed – fear of the state; pragmatism from a sense that nothing they say can change the situation; as well as resentment against western voices for invalidating some of the positive aspects of the country. At the same time, the propaganda authorities have weaponized the public sphere to wring out dissent. A critical comment posted to Weibo or WeChat might prompt the platform to delete one’s account. If that doesn’t happen, then the internet mob will pounce. And of course, a negative comment from a Chinese overseas can result in retribution against one’s family in China.

Possibly even stronger than CCP are ancient Chinese ideas about governing. The Chinese state has a very different relationship with the population than does any western state. For more than two thousand years, the Chinese state has had much greater natural authority, legitimacy and respect. The Chinese state is the guardian of the people. James Fredericks reminds us that the dominant idea in China is that of the harmonious society, not the autonomy of the individual. Daniel Bell compares harmony and freedom, meritocracy and democracy and hierarchy and equality in the US and China in his 2017 Comparing Political Values in China and the West. Meritocracy and hierarchy are valued in China. Chinese want leaders to be the best. Voting quite clearly does not give us the best leaders. In the US we do honor hierarchies in permanent government administration (the “Deep State” of educated and experienced public servants) but we don’t think about that too much. Harmony in China is as much a cultural meme as “freedom” is in the US. You can call this part of Confucian values if you wish. In any case, modern Chinese do carry stronger concepts of deference to authority and confidence that the government will act in the best interests of all.

CCP is authoritarian and can be unbelievably cruel. But to most Chinese, it is simply the government. Sometimes overly paranoid, sometimes intrusive and stupid. But mostly, people get their driver’s licenses renewed, they go to the mall and buy the same products they could buy in New York, they complain about the traffic jams and weather and they read the newspapers about the local official arrested for corruption. They go to the movies and buy books and choose to start businesses and go on vacations. This is not different from the experience of many Americans.

No question that political and moral freedoms are unavailable. CCP has its vision of the future. Mr. Xi’s “Chinese Dream” is not like the American Dream, which is a celebration of the individual and the family. The CCP Dream is a dream of a powerful CCP and a powerful Chinese state. Still, some Chinese chafe under the iron fist of CCP. They write and protest and seek change. In the west, we hear of their arrests and disappearances and think revolutionary change is in the air.

So who are the CCP who need fear persecution, arrest, and disappearance? They are mostly (not entirely) people with an ability to influence others or challenge CCP – journalists, writers, attorneys, artists. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) says there are just under 50,000 journalists, reporters and news analysts in the US and just over 7,200 criminal justice lawyers.

I have no idea how to scale the number of journalists and rights lawyers in China, except to assume that the number of journalists who could or would write stories that would offend CCP couldn’t be more than 50,000. There are attorneys who take civil rights cases in CCP for a while before they end up in jail themselves, but the number cannot be significantly different from zero.

Let’s take 50,000 as the number of potentially offensive writers and speakers and artists in CCP. That is a vanishingly small share of the population – 50,000/1,400,000,000 = 3.57 x 10-5. Double the number if you wish. Triple it. That, I submit, is small enough to ignore in China, even if we in the west give those detained and arrested and disappeared a lot of attention. This is the point at which lots of Chinese start to ask, “why do these people want to cause trouble?”

There have been experiments with elections in China. There was an election for provincial representatives in 1909 as part of the move toward constitutional monarchy. In 1912, the new Republic of China held a national election for representatives in the new National Assembly, but the outcome was made irrelevant when Yuan Shikai tried to make himself the new emperor.

Starting in 1988 and continuing under Hu Jintao there were experiments with village elections for Party chief and village president, but the candidates were still pre-selected by CCP.

There is support for a concept called democracy among many Chinese, although they have a tough time describing just what that means. It seems to have something to do with voting, but it is by no means clear how candidates should be proposed or what powers an elected official should have. Other than casting ballots, the concepts of rule of law, equal treatment under law, providing evidence in court, cross examination, freedoms of speech and assembly, alternative voices to government – these are all quite … foreign, even for some western educated Chinese.

There is voting within CCP for leaders and voting for membership in the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress. There is no campaigning for elections. There is more uncertainty in an election for high school student body president in the US.

The political system in China is described by CCP as democratic centralism. The meaning of this is a bit of word salad. From the General Program of the CCP Constitution, the Party must … resolve in upholding democratic centralism. Democratic centralism combines centralism built on the basis of democracy with democracy under centralized guidance. It is both the Party’s fundamental organizational principle and the application of the mass line in everyday Party activities.

Confusing? Following language doesn’t clarify –

The Party must fully encourage intraparty democracy, respect the principal position of its members, safeguard their democratic rights, and give play to the initiative and creativity of Party organizations at every level and all Party members. Correct centralism must be practiced; all Party members must keep firmly in mind the need to maintain political integrity, think in big-picture terms, uphold the leadership core, and keep in alignment, and firmly uphold the authority and centralized, unified leadership of the Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at the core, so as to ensure the solidarity, unity, and concerted action of the whole Party and guarantee the prompt and effective implementation of the Party’s decisions.

So … you are permitted to vote, as long as you vote for whatever Xi wants.

The current fad in CCP is promotion of “whole-process people’s democracy” which is the attempt to paint democratic lipstick on the CCP pig. Xi Jinping has determined that whole process democracy is composed of pairings of four elements-

1) “process democracy” and “achievement democracy”

2) “procedural democracy” and “substantive democracy”

3) “direct democracy” and “indirect democracy”

4) “people’s democracy” and the “will of the state.”

Xi says the combination of these results in “real and effective socialist democracy” as required in the Chinese Constitution.

Charitably, the Constitution language comes down to, “we in CCP are going to experiment with this voting thing until we understand it, and when we do, in a hundred years or so, we will provide the people with a proper version.” In the Chinese Constitution the form of government is referred to as a “People’s Democratic Dictatorship.” The preamble to the Chinese Constitution puts CCP as the prime mover, making CCP the visible hand behind the state.

As I write this in April of 2023, CCP has invaded another western consulting company in China, seeking information on auditors, management consultants, and law firms that could influence views on China. The headlines so far are about invasions of Bain, Micron Technology, and Mintz Group. Mintz is a due-diligence firm. These raids are not isolated, but part of CCP plans to control information. There can’t be a worse way to influence western businesses. To the extent such raids are really about controlling ability to think write and speak as one wishes, this is clearly harming the Chinese ability to gain cooperation on innovation and secure foreign investment in China. One can think of the raids as a war on thinking. The Wall Street Journal has more detail – China Ratchets Up Pressure on Foreign Companies.

So … probably fair to say democracy is not coming anytime soon, foreign investment is clearly at risk, and innovation will take on a made-in-China caste, unless stolen, of course.

CCP, J’accuse!

Trusting in leadership by the best

The argument made above is that technicians – engineers and finance people particularly – are bound by their training to seek rigorous or well-crafted mechanisms for solving social problems, and that these solutions are always or usually going to be second-best politically. This is Isaiah Berlin’s argument in Political Judgment as well – that good political judgment is at least an art, not a science, it is not learned in school and there is no textbook. Political judgment most certainly cannot come out of the sort of language in the CCP Constitution. In Berlin’s article there is a bit of a magical quality to good political judgment –

And we are rightly apt to put more trust in the equally bold empiricists, Henry IV of France, Peter the Great, Frederick of Prussia, Napoleon, Cavour, Lincoln, Lloyd George, Masaryk, Franklin Roosevelt … because we see that they understand their material. Is this not what is meant by political genius? Or genius in other provinces of human activity? This is not a contrast between conservatism and radicalism, or between caution and audacity, but between types of gift.

Ok to bold empiricists. But empiricists have trials … and tribulations. They test, and are tested. In fact, experience-based testing is what CCP officials get as they are promoted through the ranks.

This is not to agree with William F. Buckley about better trusting the wisdom coming from the first two thousand names in the Boston phone book, rather than trusting two thousand tenured faculty at Harvard. Buckley’s view comes closer to what we actually do in the US with regard to selecting leaders – no political vetting, no experience needed, no technical training to guide thinking, no necessary knowledge of history or psychology or human affairs. Money is needed. Nothing else. Buckley’s view is really that of the mariners on Plato’s ship of fools. It is the “my ignorance is just as good as your expertise” view. In other words, no explicit models at all of how the world works. Just feeling.

I don’t think either of Buckley’s proposed leader groups would work well. Berlin is not arguing for politicians coming into a job tabula rasa but to trust people with practical experience. Neither the phone book people nor the Harvard faculty are necessarily – perhaps ever – endowed with what Aristotle called practical wisdom.

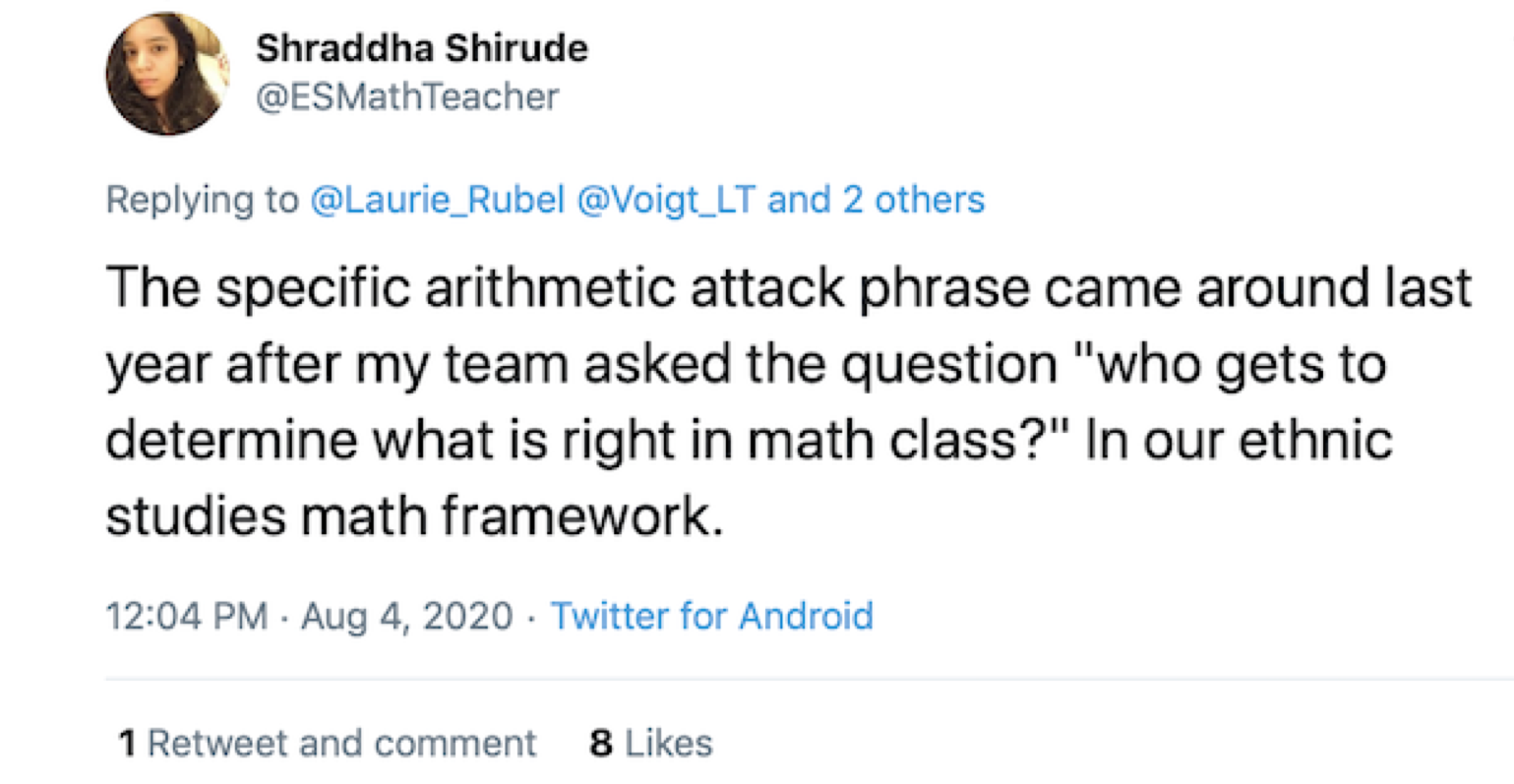

Young Chinese are aware of other perspectives on governing and values. That topic alone is worth much discussion. In the days of the May 4th movement the clarion call was for “Dr. Science and Mr. Democracy” when the old ways of Chinese culture were to be jettisoned in favor of western ideas. Then later came “look west for science, China for culture” when political and moral freedoms began to seep in with the science and engineering.

Many of them have spent time in the US. Now, not so many of them are desirous to stay in the US.

Numbers games are too often false flags. But let’s try one – for some years (not so many anymore) there were about 300,000 Chinese students in the US, most of them in college or graduate school. Just for ease, let’s say there were about 100,000 graduates returning to China each year. In ten years, that would be a million students. Within China there are about four million graduates of four-year schools each year now, and another four million graduates of certificate and diploma schools. In ten years, that would be eighty million. Of course ideas are a common resource, a public good if you will. But along with some understanding of free speech, Chinese are now returning from the US with a large dose of exposure to violence, gun murders, racism and poorly functioning institutions. It used to be that Chinese students would try to stay in the US. Some still do. But more and more they return home for better job prospects and a safer life. By no means do all returning Chinese students carry a rosy picture of life in the US. For many of them, the US looks rather barbaric when compared with their life in China. American soft power in terms of lived experience is a bust.

Democracy and capitalism united

Martin Wolf in his new book The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism argues that capitalism works best when it works with democracy – but also that democracy works best with a capitalist system. The two are inextricably linked in terms of promoting equality – one an equality of persons and the other equality of a volume of money. Either fails if the other becomes too powerful. One can see the Acemoglu and Robinson “extractive v inclusive” dichotomy from Why Nations Fail. Obviously capitalism can become oligarchic and extractive. Rather than serving customers, employees, or even stockholders, it serves senior management. Democracy too can become extractive, when too much power devolves to one group or one party in a plural society. Excessive regulation is the obvious example. Remember that in 2023 the legislature in Florida is seeking to ban Chinese from buying property in the state. And homelessness and “housing failure” is at least a regulatory failure as much as a failure of health or education or social service policies.

Wolf summarizes – The enemy today is not without. Even China is not that potent. The enemy is within. Democracy will survive only if it gives opportunity, security and dignity to the great majority of its people…. If elites are only in it for themselves, a dark age of autocracy will return.

We apply the word freedom to things we find desirable in both capitalism and democracy, but they require freedoms of very different kinds. The distinction is often not noticed. I think the word freedom is the link that many people have in mind when we discuss innovation and GDP and democracy. The freedoms of speech and association in democracy provide for human dignity, but these are distinct from economic freedoms. Chinese people have as much economic freedom as Americans do, but no one would call Chinese people “free.” The distinction we should make in capitalism is that the path of success for a society is in competitive markets, not free markets.

The important point for us here is that capitalism and democracy can work together, but need not. There are plenty of countries that make efforts at democracy, but fail to encourage much of a capitalism with generally competitive markets. And we have China, with lots of competitive sectors of the economy but no moral freedoms, and no particular desire to alter the mix. The extractive elites in China – mostly CCP – will work hard to keep their relative position as occupiers. If Martin Wolf is right, a dark age of autocracy may still emerge in both the US and China. We may be seeing the beginnings right now.

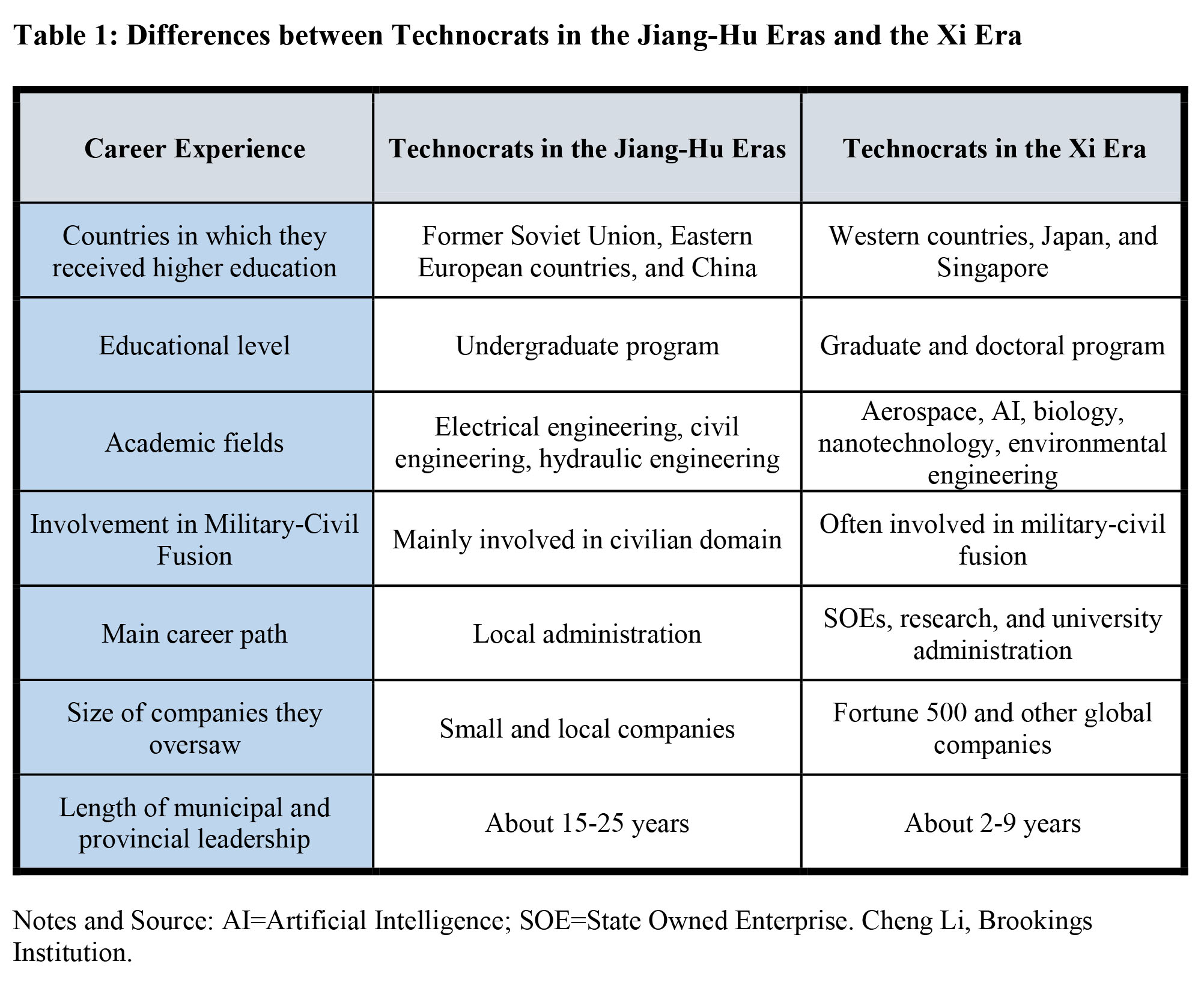

Some see the engineering, economic and finance backgrounds of many leaders, including Xi, and see lack of humane feeling in governance – that these technocrats are best at working with the physical rather than the human. And by its nature CCP wants rational solutions. At some point their ability to hear as the people hear, see as the people see will fail.

But leaders at every level of government are by no means all technocrats. As leaders rise in authority, they gain more and more of that practical experience Isaiah Berlin touted to accompany any technical training they might have obtained in school. And they pay attention to what the people are saying.

To hear and see, leaders are adept at using technology to measure citizen attitudes. Censorship does not imply ignoring what was posted and who posted it. Close monitoring of people’s posts and comments and attitudes is itself an industry in China. CCP does hear as the people hear, sees as the people see, as heaven is supposed to do in the mandate of heaven. Just the CCP response is always … measured. And to be fair, it sometimes took heaven a decade or two to respond as well. But if CCP provides voice to Chinese people, it is providing a sense of human dignity that can make “democracy” unnecessary – as it has in Singapore.

Let me point out that Chinese leaders – certainly those I know in special economic zones and districts of cities and counties and provinces – go through training and vetting processes with which Americans are absolutely unfamiliar. Not only do college students have to pass the standard government entry exam, held once each year. The exam has two parts: an aptitude test with 135 multiple-choice questions on math, world affairs, language, and logic that lasts two hours. Test-takers have another three hours to write an essay. About 1% or 2% of test takers pass. For those who pass, there are additional special or technical exams. Once ensconced in a government position, training is not over. Anyone being promoted to a new job receives training for that job. Sometimes the training is at the city or provincial School of Administration, which doubles as CCP party school. People in many mid-level administrative positions are exposed constantly to others in similar positions via two or three day meetups, in the same or other provinces, by way of getting seasoning and exposure. And there is not the rather extreme division one sees in American politics versus administration. One can mature from a lower level government administrative position into a higher and more political position, which does happen in the US as well but I think to a far lesser degree. Certainly no one comes from private business in China to government service with the threat to “run government like a business.” There are no ignorant buffoons in higher positions in Chinese government. They are vetted out long before. There are people who are corrupt. But for most the good of the Party and the country comes before personal aggrandizement. And ability to control popular dissent is one evaluative measure by which to judge readiness for promotions. That ability does not come from any technical training. There can be voice without democracy, and that is what CCP provides. (See post #1 in this thread).

The central government zuzhibu organization department controls the top 5,000 positions in the party and government. This includes all ministerial and vice-ministerial positions, provincial governorships and First Party Secretary appointments, as well as appointments of university chancellors, presidents of the Academy of Science and Academy of Social Sciences, etc. Provincial, city, county and university organization departments vet people at their levels as well. The vetting is not proforma. The Chinese attitude is why, oh why, would you let someone ignorant of the requirements of a job be a leader in that department or ministry? Those 5,000 or so senior positions are filled by people who have the Chinese IBM experience – I’ve been moved – to different cities and provinces across China to provide experience and ability for the zu zhi bu to judge ability under stress.

Sometimes we have the idea that the way we do democracy in the US is the only real way. But other countries do democracy also, with a wide variety of means. And all countries use a mix of openness and control to get to governance. People generally can be satisfied, even happy, with a wide variety of governance systems.

Perhaps we would be better off if we understood democracy as simply a way to provide voice, and thereby express human dignity. We don’t have to win every time we vote, but we want to know that we are heard. And we could understand capitalism as allowing people to make their own economic choices. Democracy and capitalism must defer to the other at times and to what people decide they want. There cannot be a normative democracy or a normative capitalism.

Modern economies are complex. Modern social problems are complex. Successful governance requires more than technical expertise or book learning and more than paying attention to profit and the bottom line. So tell me – on the ship of fools, who do you want as navigator? The pure innocent, the ignorant noble savage, or the sailor who knows how to use a sextant, has sailed before and can communicate his findings to the crew? It is not just technical knowledge and it is not being glib. In the US we do rely on technical staff with deep experience to advise leaders. We don’t expect experience, expertise or wisdom in our leaders. Chinese do expect those traits, and rather often, they get them.

It is a mistake to see “China v US” as a contest between -isms – “democracy v authoritarianism” struggle or Slater’s “control culture v integrative culture.” These terms are too ill-defined and far too broad. For most people the government is just … government. They don’t want to interact with it. They want it to be procedurally fair and understandable and they want human dignity. Otherwise, they mostly don’t wish to deal with government at all.

All governments consider what they have to do to remain in power. They take what actions are necessary and otherwise work to please their funders, supporters, friends. For China that means CCP can be quite flexible locally. Remember that in 2002 Jiang Zemin invited capitalists and business owners into CCP after killing hundreds of thousands of them fifty years earlier. A provincial or municipal party chief in some east China province has to be attuned to what the people want. This is the artistry of power that Robert Hariman discussed in his Political Style – The Artistry of Power – how matters of style – diction, manners, sensibility, decor, and charisma influence politics. That can certainly describe the machinations of power within CCP. This is part of the practical reasoning that Isaiah Berlin and Aristotle proposed.

Matters of style carry on even when away from home. A very minor example. At IIT in Chicago, we held an end of year party for our Chinese government students. One year, we had the leader from each of the three groups deliver some short remarks. We had government officials from cities around Liaoning Province. Liaoning has a deserved reputation as home to heavy industry – coal mining, oil, steelmaking and chemicals. We had officials from Dalian, also in Liaoning but sophisticated and international in a way that the rest of the province was not. And we had officials from Hangzhou, the wealthiest city in one of the wealthiest provinces, and very cosmopolitan. The Liaoning leader was nicely dressed for his remarks, with a light black leather jacket over a dress shirt, no tie. The Dalian leader wore a dress suit and tie. The Hangzhou leader wore a sport jacket over a light sweater. To me, each style of dress reflected the socio-economic status of their home base, from less cosmopolitan to more so, whether by intention or not.

Life for middle class Chinese is … at least ok. It is pressure filled and there are worries about jobs and spouses and the kid. Not different from life in the US. Rural poverty in China is bad. It is bad in the US, too. Health care is poor for many in China. US medical system, heal thyself. Schools, ditto.

Chinese can and do complain online about local problems – potholes and noise and air quality. Metaphorically, as long as the garbage gets picked up it does not matter who runs the government. Freedoms of speech and press and religion and association are fairly existential worries.

Locally …

There are benefits to not having to worry about politics. Chinese do not walk around with a fear of being attacked on the street or their kids being murdered in school. There are poor people begging on the street in some places, but they are not to be feared. There are thefts and robberies and arguments on the street and killings. But nothing like the threat of daily violence we have learned to live with in USA.

Short of wars and natural disasters, people … well, cope. Lying flat (tang ping) is coping, but it is not going to be a life-long practice for most. Maybe a few weeks.

Sometimes we get distracted by the simplicity of econ 101 and supply must equal demand and Newton’s third law and every change ostensibly for the better has its attendant, if subtle, costs.

Sometimes we get distracted by the authoritarian stories coming out of China and think that the people are uniting in opposition. We remember “The People … United … Will Never Be Defeated!” But that assumes that the people are really uniting against anything. It probably is worthwhile to point out that the authoritarian horror stories are of most interest to those of us in the US for whom free speech and association are most directly relevant. And perhaps it is worthwhile to remember the old adage about Chinese – “no people more discontent and no people less revolutionary.”

James Fredericks again, in Confucianism, Catholic Social Teachings, and Human Rights –

The Chinese state enjoys a very different kind of relationship with society compared with the Western state. It enjoys much greater natural authority, legitimacy and respect, even though not a single vote is cast for the government. The reason is that the state is seen by the Chinese as the guardian, custodian and embodiment of their civilization. The duty of the state is to protect its unity. The legitimacy of the state therefore lies deep in Chinese history. This is utterly different from how the state is seen in Western societies.

The US has its own problems with uncaring government and political officials. The rest of the world looks at our obsession with guns and our lack of obsession with poverty and health care and abysmal schools and moronic public officials and they now look elsewhere for spiritual encouragement. I don’t have any data, but I would be there are few immigrants to the US from anywhere in the developed world.

When it comes down to it, we always need to find a balance. In the American system, as destructive and heartless as it is, most of us find a way to balance need for stability and change. Chinese do similar things, starting from a different social place. It is, frankly, a toss up as to which society manages change better. If one thinks Chinese don’t manage change well, how did they do what they did in the last forty years?

When we too closely link democracy and capitalism, or innovation and political freedoms, we make a category error. Capitalism and democracy do need each other, but only at the margin. Both have an infinite variety of expressions in customs and institutions. All governments, however, need to provide for expression of human dignity.

Ci Jiwei analyzed the modern Chinese moral problem in his 2014 Moral China in the Age of Reform. He sees the lack of empathy, the corruption, the obsession with conspicuous consumption as symptomatic of an inability to express oneself, to express human dignity. There is almost complete lack of moral freedom, to express oneself in speaking, writing, reading, association. Ci sees democracy as a way for people to express human dignity, but there are other ways as well. I wrote a series of posts about moral freedom three years ago at What is this Moral Freedom Business?

Ci notes that modern human societies need to provide for individual human dignity, and dignity is expressed through agency – how do we interact with others to achieve our position in the world? He sees agency expressed in two ways – through freedom or through identification with a superordinate idea. Agency expressed through freedom leads us to thoughts of democracy. Agency expressed through identification with a cause or charismatic leader leads us to thoughts of authoritarianism. But if agency either way is expressed in customs and institutions and laws and regulations, how many different varieties can there be? There just isn’t one form of any -ism that is normative or definitive.

This discussion is getting a bit past my pay grade. I want to make the point that China doesn’t have a system that we would call capitalist, but capitalist it most certainly is in many ways. China doesn’t have a system that we would call democratic but it provides a certain amount of voice for its people. If we look at governments in the US and China, they have many similar responses to social needs and many similar problems going forward in the next decades. Both will need to spend more money on people and less on things. Both will need to do more to provide dignity for their people. China has come as far as it has in the last forty years with a system that we think of as unworkable, but work it has. To say that suddenly now it is unworkable is an unwarranted conceit. To say that the US has the only workable system of democracy and capitalism is also a mistake. My contention is that human dignity is satisfied in many forms. There is no reason to think China – even CCP – cannot find a way that allows it to prosper, even innovate.

Its tricky to use cities as examples of democracy or innovation. Cities are complex beyond anything we can easily write about. Hong Kong has been cited as an example of capitalism par excellence; it was really more corporatist than capitalist. Its version of democracy was not one that Americans would find appealing. But what moral freedoms did exist are now being erased quickly. In the new school books, Britain never governed Hong Kong and newsrooms are empty. Thousands of people have fled, and lots of businesses have decamped for Singapore or Bangkok.

We can see the capitalist-corporatist system working even as the democratic one is erased.

Hong Kong is being remade almost faster than the changes can be reported, as if the whole city had suddenly been unzipped to reveal a shadow society lurking beneath.

Many key institutions — civil society organizations, political parties and trade unions — have dismantled themselves in the ultimate act of debasement. In 2016 elections, pro-democracy or other nonestablishment figures won about one-third of Hong Kong’s legislature. After a drastic overhaul of election rules and a resulting boycott by democratic parties, a 2021 vote returned just one nonestablishment lawmaker out of 90 seats. Hong Kong’s population shrank for three years in a row because of emigration and a falling birthrate.

Friends who are still there tell me they no longer talk politics, even with family or close friends — this in a city that was once defiantly political. One friend spoke of wanting to like a Facebook post of mine but not daring to. In that tiny nonaction, a failure to click, the individual becomes complicit, accelerating the degradation of memory.

CCP is working as fast and as hard as it can to erase memories of moral freedoms. Democracy is not coming to Hong Kong.

I said in previous posts that my Chinese undergrads did not recognize the famous “tank man” photo from Tian’anmen in 1989. They were born in 1990 and after. Few people would talk about that time and there were no images of value. Erasing that part of history from social experience took less than a decade. Some of my curious students did ask me what happened in June of 1989. I gave them copies of the two-part Gate of Heavenly Peace movie –

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Gtt2JxmQtg and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o0lgc4fWkWI&t=4163s

The Chinese language version – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RA-UQyCZskA

The videos on my thumb drive were a very small contribution to historical memory and being able to see and think for oneself. CCP was able to declare victory after Tian’anmen and it will do so after Hong Kong. Memories of Tian’anmen and Hong Kong are preserved outside China; but what matter that?

If anything, financial capitalism sees democracy as irrelevant. Chinese companies and corporatist foreign companies will do just fine, thank you, without a democratic polity. How easy would it be to get big American companies to restrict themselves from the Chinese market?

Many American companies have left the Russian market; but that was marginal. There’s too much money to be made in China for political freedoms to be of concern. We are at “what’s good for (insert name of major international company here) is good for America.” That wasn’t what Charles Wilson said in 1953 but it seems quite relevant now.

Going deeper, American culture of individualism has told us, forced us, to be good at adaptation. We don’t have resources upon which to fall back – extended families, the neighbors, clans or the church. Now, even unions and schools and local governments are less available to pick us up when needed. We get counseling but we don’t get much help. One wonders, with Christopher Lasch in The Culture of Narcissism how a society of sovereign individuals, not paying attention to the needs of others, can long survive. I liked this comment from a recent post: “Americans do not agree about the duty to protect others, whether it’s from a virus or gun violence.”

That is not the cultural Chinese view, regardless of how closely it might not be followed in practice.

China has similar modernism adaptation problems but is starting from a different place. Jobs and social services and society were always available in the family, the clan, or the lineage group. Even the most modern and upwardly mobile Shanghainese financial advisor has a family home back in some village somewhere. It might be a supreme embarrassment to move back in with grandma, but it is a safety net. Family remains the locus of support, from pitching in to fund college education abroad to buying that first apartment. Grandparents and uncles are regularly involved in education donations. We just don’t have nearly the level of family support that one regularly finds in China.

We also don’t have nearly the willingness to let government have the benefit of the doubt in enacting policy. That is partially due to fear of retribution, true. But the government is not ignorant of the wishes of the population, as we saw with the sudden relaxation of covid restrictions last fall.

China has big problems, some of them looming natural disasters like climate change and water scarcity and some manufactured by CCP modernism and policy – hukou restrictions and poor education and health care and fevered promotion of spending and buying. The US has big problems too, some of them looming natural disasters like climate change and water scarcity and some manufactured by racial enmity and financial capitalism – restrictions from zoning laws – the American hukou – and poor education and health care and fevered promotion of spending and buying.

If Chinese look at America now, not the shining city on a hill from fifty or a hundred years ago, they mostly see a social system they do not want for themselves. Sure, there are some good things about America, but the risks are high.

This democracy thing isn’t quite as attractive as once thought, back in the early 20th century when Mr. Science and Mr. Democracy were all the intellectual rage, promoted by none other than Chen Duxiu, one of the founders of Chinese communism. How times change.

Every country has its own understanding of capitalism and its own understanding of democracy. This is to say, every country has its own ways of letting people find agency for themselves and express human dignity. In these posts I tried to suggest that notions of freedom – economic and moral – exist on a wide spectrum. China is an easy place in which to live if one is only concerned about economic freedom; not possible if one is concerned about moral freedoms. Nevertheless, people cope. Some want significant change, and will take risks to accomplish that. Mostly they love their homeland and don’t want to see too much change. People do that in the US, too.

Links to Related Articles

Change Management 1/3

Change Management 2/3

Change Management 3/3

Source:

Source:

On passing the academic intellectual torch

William Kirby is a renowned China scholar at Harvard. He has written a dozen books on Chinese history and our relations with China. He has a long list of accomplishments at the highest levels of international academia and professional societies.

When he writes about superior universities in Germany and the US and China, I can only marvel at the scope of his erudition. So I feel a bit out of my element commenting on his latest book Empires of Ideas: Creating the Modern University from Germany to America to China.

Kirby writes that on academic engagement with China the educational resurgence is much less a threat than an opportunity for American and other international universities…. American research universities have been strengthened enormously by recruiting Chinese doctoral students, themselves largely graduates of Chinese universities, who are admitted exclusively on the basis of merit. Our faculty ranks, too, are augmented by extraordinary Chinese scholars. We restrict these students and colleagues at our own peril. Today, any research university that is not open to talent from around the globe is on a glide path to decline.

True enough. Kirby is familiar with the finest research universities and students in China and the world. Some Chinese students go on to excel in academia and business, scientific and professional worlds in the US and China – fewer right now in the US, and that is an issue for American xenophobia.

Kirby is talking about intellectual leadership. In his historical progression, the 19th century German university model of openness and serious intellectual pursuit passed to the US in the 20th. He says the leading research, learning and education model for the 21st century is now being passed on to Chinese universities. No nation has greater ambition than China, or ability to devote resources to higher education.

Kirby’s approach to international cooperation is what one would expect from a man with so many interconnections – diplomatic and deflecting on sensitive issues and no one can fault that. It is sophisticated and mature. In Empires of Ideas, one is reminded of the marketplace of ideas, the informal, collegial and multinational networks that were part and parcel of the Enlightenment. Free exchange of information and ideas advanced science and engineering and freedom. True then, and true now.

I want to push back a little, though, basically to report on what I’ve seen at schools not in the top ten of universities in China. Kirby sees engagement with Chinese universities as an opportunity, not a threat. I agree. More exposure to the world is a good thing. But we should not fool ourselves into thinking that (1) there are always good intentions behind the dinners and smiles; and (2) most Chinese students are international work-force caliber.

On (1), no one should assume that exchanges are all collegial. CCP has weaponized exchanges within the academy and between businesses. For evidence, one need look no further than the hundreds of cases brought by the FBI against researchers, Chinese and American, seeking to steal IP from university labs and from businesses. FBI director Christopher Wray’s “whole of state” threat from China is not hyperbole.

On (2), no one should fault Kirby for addressing the university environment with which he is familiar. But most schools, faculty, and students are not in that top 5% internationally. We know the myriad stories of cheating and plagiarism in schools in China, and students who come to the US with the same attitudes toward doing the work. I’ve seen myself how lack of respect for honest work tends to bring down the performance of an entire class, including that of domestic students. We know the Yale-Peking University program was cancelled in 2012, partly attributable to allegations of widespread plagiarism and cheating.

Dishonesty in academic work is not unknown among American students. But I know of many instances in which faculty at schools in China simply turn their backs on cheating in exams. And they get little administration support when they try to restrain the dishonest behavior.

We know cheating on the college entrance exam – the gaokao – is controlled more now than a decade ago, when attempts to control cheating resulted in an angry mob of 2000 parents yelling at test administrators. “We want fairness. It’s not fair if you won’t let us cheat.”

The national push in China to control cheating resulted in some odd experiments. At our school in Hangzhou the new president decided to promote an honor code in final exams, as is the case at nearby Zhejiang University (Zheda), one of those top schools in China. This is not to take anything away from Zheda. There is an honors option in the Global Engagement Program, designed to cultivate Chinese students for work in international organizations. The program is conducted in English. Professor Kirby would be happy to engage with these students, some of the best and brightest in China.

But at our provincial-level school an exam honor code was DOA among both students and faculty – no one thought it could work. The only faculty member who could give voice or pen to objection, though, was me. Everyone else had careers on the line. I didn’t have to care. But what the president wanted, the president got.

Before the honor code was to be implemented, I did my own experiment. In one economics course I had plenty of scores from homework, quizzes, and a midterm to provide final grades. I had noticed years before that a final exam with a significant weight – 30% or 50% of a final grade – almost never changed a grade from that going into the final exam.

In class we had some discussion of the honor code. I proposed an experiment. The final exam would only count 10% of the final grade. But I would hand out the exams and leave the room for two hours and we would see what result. No monitors in the room. If students cheated, others were supposed to report them to the instructor for consideration, as the university president proposed.

I also arranged with six of my very good students, three foreigners and three Chinese, to take the final exam a day earlier and then take it again during the whole class exam. In the whole class exam they were to very obviously cheat in any way they wished, but so that other students could see. Open textbooks, read from notes, use phones, copy from other students. Make it obvious. And oh, yes – the whole class exam was different from the one I gave my star students.

You can guess the result – my good students cheated as best they could, and no one reported them to me. When my six finished the exam, they hung around outside the exam room and took pictures of students getting up from desks to look at other exam papers and using phones with abandon.

I don’t know if you call the experiment a success or a failure. But no one told me I had to use the honor code in subsequent semesters.

There is little sense of honor built in to these students. Lots of American students are no different. But an honor code needs good intentions. What good intentions do exist can get waylaid by pressures from family, culture, and particularly CCP.

Kirby is impressed by the earnestness, even in the current days of trauma and contestation, with which Chinese academics pursue joint arrangements with American schools. On one hand, that is understandable. Chinese academics are desirous of contacts for academic and personal reasons (including the ability to publish in western journals and to get their own kids into American schools). Kirby alludes to the CCP corporate overlords that can work to encourage or discourage such arrangements. For a few years before 2012, university joint ventures of all kinds were the rage. CCP pushed for engagements and wanted measurable results. A couple of my Chinese government students from Chicago were responsible for those foreign outreach programs. The pressure to get some agreement was palpable – one-way semester exchange, two-way, with or without American faculty in China, some sort of joint program, and even in some cases a joint degree with an American school. My school had a joint civil engineering degree program with San Francisco State University. A couple of years in China and then to the US for the last two or three years. The American degree was worth something. The Chinese degree – not so much. Until recently there was no international accreditation for most Chinese engineering degrees.

We need the Chinese students, undergrad and PhD candidates, for our own development. But we should not lose sight of the ill-preparedness and ill will that still lurks.

Plenty of Chinese, students and families, come to the US for education and business and – dare I say it – the freedoms that accompany a green card. There are tens of thousands of Chinese immigrants to the US each year – 150,000 in 2018. I know several student immigrants personally- come for the advanced degree, stay for the high-paying job. Quite often, their parents tell them not to come back to live, but to stay in America.

Not so many Americans go the other way.

Kirby is right to promote engagement for the good of American schools and students and faculty. Some Chinese universities may well join the upper ranks of international schools in the next ten years. But I hope he – and other administrators and scholars – can go into the engagements with a bit of the skepticism and hard evidence-seeking that led to dismissal of Confucius Institutes at the University of Chicago, Penn State, William and Mary, SUNY, Oklahoma, Texas A & M and others and cancellation of the Yale-Peking U program and consideration of the continual warnings of Chinese deception and theft from attorneys experienced in Chinese business arrangements. Harris Bricken is a good example.

We can take a hint from Ronald Reagan’s treaty policy with the Soviet Union – trust but verify. The expensive dinners and gifts and warm smiles are enticing. Its easy to become enamoured under the influence the velvet-gloved fist. I keep thinking of Sergeant Phil Esterhaus’ warning to street cops before going out on patrol in Hill Street Blues –“Let’s be careful out there.” It can be hard to do that, especially after the wining and dining and graciousness of their potential partners. But Kumbaya this ain’t.

I don’t have hard recommendations for administrators of great American universities. But they should jealously guard the reason they became great in the first place – freedoms of expression, dissent, and honesty in relationships. Too often we have let the Chinese camel’s nose into the academic tent to the detriment of American academic quality standards, research and innovation. A little caveat emptor is always a good idea.