The question to Gandhi is now being asked again, this time by educated, sophisticated Chinese of each other.

This was the topic of a four-hour phone call a few nights ago between Chinese PhDs, both with extensive American experience and important midlevel career positions.

In a word, their conclusion was the same as Gandhi’s – it would be a good idea.

Their argument below is depressing, as if you need any more of that. I am paraphrasing in spots and retelling in what follows. My own Chinese language skills couldn’t have kept up.

For my colleagues and for many educated Chinese, the US and the west have been the model of civilization – educated, smart, democratic, highest technology and culture, in a word, modern. Human rights were honored, even if not always observed in the breach. This, coming from Chinese who know that historically, Zhongguo was always considered the center of the universe.

A little background

That the west was the center of modernity was an idea nurtured over a long span of time, probably going back to the era of treaty ports in the mid-nineteenth century. Out of the humiliation of the 19th century came the May 4th movement, which sought to replace millennia of deference to authority and superstition with “Dr. Science and Mr. Democracy.”

Ancient Chinese culture was … well, ancient and feudal. Chen Duxiu, founder of the Chinese Communist Party, saw modernism and personal independence as the conditions necessary for growth. This was in 1916.

The US remained the modernist pole star for the next hundred years. The term for the United States, meiguo, means beautiful country. But by 2010, many Chinese believed in the American dream and an American miracle more than did many educated, sophisticated Americans. Chinese were not ignorant of American deficiencies – racism, poor schools and health care for poor people, a developing oligarchy, gun nuts and chaotic politics – but democratic values seemed able to pull victory from the claws of every looming defeat, and all that was necessary was a little money to get world class schools, education, health care, and a peaceful life. John Dewey had been a popular figure in China, and above all, America was seen as pragmatic.

That was then, this is now

That was the image, and it is no more, my colleagues said in the wechat call. America has been the standard, but they also considered western Europe, and found it wanting as well. America – and the west – seem in thrall to an ideology, not one my interlocutors could identify, but it was definitely not pragmatic.

This democracy thing – perhaps more precisely, individualism – has met its match. The covid-19 virus is only the latest and most clearly defining symptom. Democracies, they said, seem unable to do basic things that improve the lives of most people. A hundred thousand dead is an acceptable level of loss? Policies that pit states against one another to obtain PPE? The interlocutors on the phone call couldn’t get to evolving deficiencies in laws, regulations and institutions that were the subject of Why Nations Fail (Acemoglu and Robinson). Nor had they read How Democracies Die (Levitsky and Ziblatt). The sense was the American promise was now – well, if not a lie, at least more marketing than substance.

I have many Chinese government friends and associates, some of whom have made moves to purchase real estate in the US for retirement or for their kids to go to school here, or just in case. Those days seem over, and not only because of the egomania of the leaders Xi and Trump. The America that was promised is now an uncertain risk. Who knows what part might fail next? Metaphorically, the American car used to be new and shiny and had the latest gadgets. It was safe, everything worked, and the warranty was sound. Now the American car is a used car, and if you look under the hood, it gets pretty scary. The warranty is barely worth the Constitution it is printed on.

This jaded view of the US and the west is not new. Chinese university students in America have been coming home to China for a decade, unimpressed by the lure of freedom of speech and democracy that comes at the cost of guns and mayhem and ridiculous health care expense. Now world news and opinion is flush with incredulity and alarm about the US.

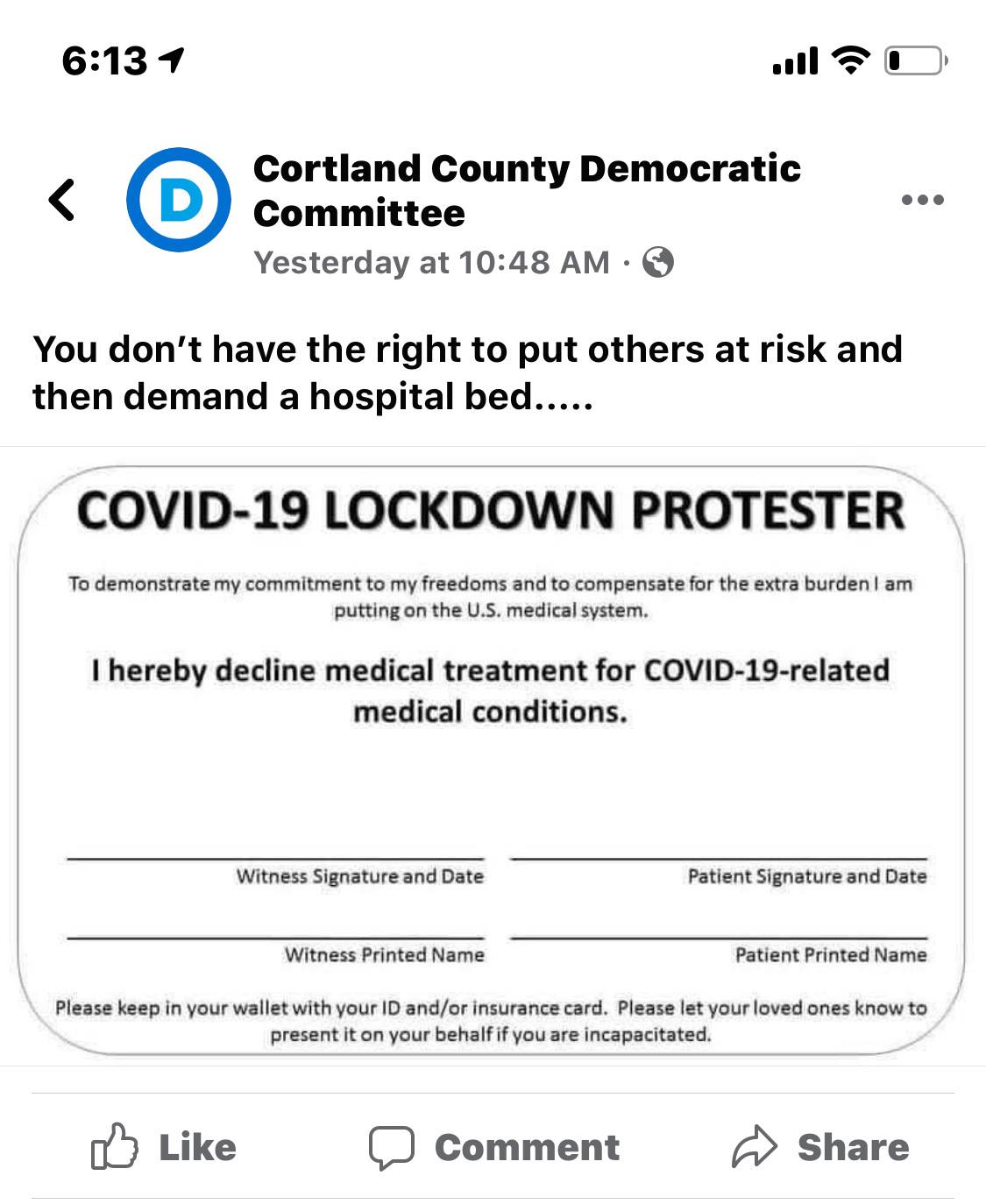

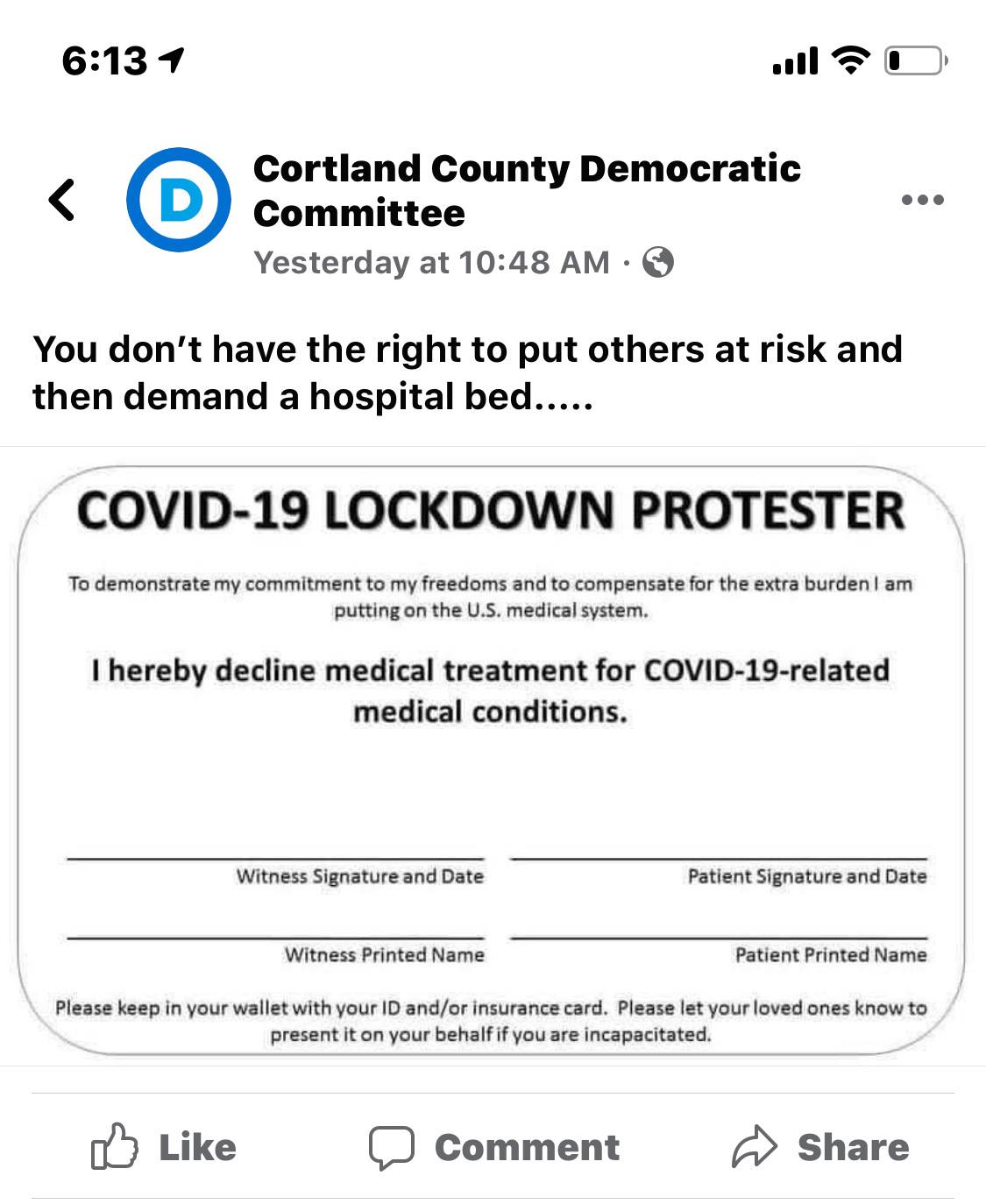

There is little sense of individual responsibility and little concern for the other, said my colleagues. Freedom to die is apparently the mantra for those now rushing to bars without masks or distancing. Chinese would say, good luck to them. And, they say, the Cortland County New York wallet card should be made mandatory in Wisconsin, Georgia, Florida – anywhere the stupid people congregate.

The comparisons with China are easy and superficial, and my colleagues were speaking only in personal, offhand remarks. Their feelings about the Chinese government in January and February were very negative. Now, looking at the rest of the world, they have a different idea. China bungled badly in the first six weeks or so of the virus time, but with testing and lockdown, distancing and quarantine and tracing, it basically beat the virus in two months.

There was no expressway driving allowed. If people were infected, they were isolated away from their families. Temperatures were taken going in and out of residential complexes. People’s level of cooperation was very high. It didn’t matter if you were young or old, rich or poor, lives were treated as more important than the economy. Now that cases have shown up again in Wuhan, the plan is to test all 11,000,000 residents in the next couple of weeks. We can discount real implementation of that plan as fanciful, but nevertheless, the government will test and isolate and trace, and that will work. Individuals bear no cost for treatment of Covid-19, from testing to ventilator. There is no point in staying away from the hospital if you are sick because you can’t afford it. All things considered, including that the virus started there, they said, China had about the best possible response.

One can quibble. This was their considered evaluation.

In the US – well, you know the news stories. The rate of new daily cases has still not fallen in two months, to May 23. And that was with two-months notice before shutdowns began. On the phone call, my Chinese friends were appalled at the ignorance and sheer stupidity. The Michigan legislature shut down rather than confront gun wielding freedom-to-die fighters who deny medical expertise. If I don’t wear a mask, and I infect you, so what? Leaders tell old people to die for the sake of the economy, and everyone should drink bleach. Neither Dr. Science nor Mr. Democracy are in evidence. Who are these people? Left unsaid, I think, was the question of whether these can be real humans at all, but there certainly was a sense of the inmates running the asylum. Over the next few months, will we really accept 2000 deaths a week as the cost of doing business? Is this what human rights comes to?

My colleagues used Marx for reference. The first stage of capitalism was certainly ugly. Marx said that every pore on the skin of the workingman was filled with blood or dirt. But wealth bought respectability and human rights talk, and this worked pretty well until the real control and desires of the capitalist class were exposed in 2020. The political leaders and a lot of citizens are in thrall to the economic oligarchs.

A story about a woman named Peggy Popham from North Carolina summarizes the views of my colleagues that a good portion of Americans are just … well, nuts – The coronavirus pandemic created the perfect environment for apocalyptic Christianity to fuse with antigovernment libertarianism, New Age rejection of mainstream science and medicine, and internet-fueled gullibility toward baroque conspiracy theories about secret cabals ruling the world through viruses. About twenty percent of Americans have said they would not take a vaccine when available.

The rejection of science and rationality, they said, means the US can no longer be considered modern. Other Chinese agree. In a recent article, Wu Haiyun, editor at Sixth Tone, echoed the feelings expressed on the phone call, but she was referring to Chinese now in their late thirties and early forties – Trust in Science Saved China. Practicing It Will Keep It Safe.

This Chinese view is not itself isolated

Edward Luce at Financial Times writes about the world’s view of America now, and it is not pretty – William Burns, most senior US diplomat and now head of the Carnegie Endowment – America is first in the world in deaths, first in the world in infections and we stand out as an emblem of global incompetence. The damage to America’s influence and reputation will be very hard to undo.

The Guardian suggests that the world looks on in horror at the US response.

And Fintan O’Toole writes in the Irish Times – Over more than two centuries, the United States has stirred a very wide range of feelings in the rest of the world: love and hatred, fear and hope, envy and contempt, awe and anger. But there is one emotion that has never been directed towards the US until now: pity.

Another colleague of mine whose tax clients are mostly foreign nationals remarked that part of what he had done for forty years was enable people to live, work, or make a living in the US. Now, he says, he is dealing with the converse – people wanting to move assets or themselves out.

What is to be done?

Now, if you have choices about where to live in the world, where to go? If you have kids, what is a safe and humane place with expectations of solid education in which to bring them up? Where will a kid be more easily cultivated as a right-valued person? The virus seems the last straw.

For my colleagues, this democracy thing has come to mean not that citizens are empowered to obtain information and make educated choices, but that “my ignorance is just as good as your expertise” and more to the point, “every man for himself.” No democratic founder in Athens, the Colonies, or political philosophy in any era would support that view.

This is what the American image has come to. Evaporation of American soft power cannot be far behind. The vaunted American Dream has become a version of Is that all there is? Robert Frost considered whether the world would end in fire or in ice. Neither, it turns out. The world as we know it ends in willful ignorance and stupidity. The scientist, the doctor, the researcher, the humane and rational end up looking like navigators on Plato’s Ship of Fools. “Fake news,” is what my Chinese colleagues said about this alarming American discrediting of science – but they meant that people could not distinguish science from lunacy. Good luck to those Americans, is what they said at the end.

On passing the academic intellectual torch

William Kirby is a renowned China scholar at Harvard. He has written a dozen books on Chinese history and our relations with China. He has a long list of accomplishments at the highest levels of international academia and professional societies.

When he writes about superior universities in Germany and the US and China, I can only marvel at the scope of his erudition. So I feel a bit out of my element commenting on his latest book Empires of Ideas: Creating the Modern University from Germany to America to China.

Kirby writes that on academic engagement with China the educational resurgence is much less a threat than an opportunity for American and other international universities…. American research universities have been strengthened enormously by recruiting Chinese doctoral students, themselves largely graduates of Chinese universities, who are admitted exclusively on the basis of merit. Our faculty ranks, too, are augmented by extraordinary Chinese scholars. We restrict these students and colleagues at our own peril. Today, any research university that is not open to talent from around the globe is on a glide path to decline.

True enough. Kirby is familiar with the finest research universities and students in China and the world. Some Chinese students go on to excel in academia and business, scientific and professional worlds in the US and China – fewer right now in the US, and that is an issue for American xenophobia.

Kirby is talking about intellectual leadership. In his historical progression, the 19th century German university model of openness and serious intellectual pursuit passed to the US in the 20th. He says the leading research, learning and education model for the 21st century is now being passed on to Chinese universities. No nation has greater ambition than China, or ability to devote resources to higher education.

Kirby’s approach to international cooperation is what one would expect from a man with so many interconnections – diplomatic and deflecting on sensitive issues and no one can fault that. It is sophisticated and mature. In Empires of Ideas, one is reminded of the marketplace of ideas, the informal, collegial and multinational networks that were part and parcel of the Enlightenment. Free exchange of information and ideas advanced science and engineering and freedom. True then, and true now.

I want to push back a little, though, basically to report on what I’ve seen at schools not in the top ten of universities in China. Kirby sees engagement with Chinese universities as an opportunity, not a threat. I agree. More exposure to the world is a good thing. But we should not fool ourselves into thinking that (1) there are always good intentions behind the dinners and smiles; and (2) most Chinese students are international work-force caliber.

On (1), no one should assume that exchanges are all collegial. CCP has weaponized exchanges within the academy and between businesses. For evidence, one need look no further than the hundreds of cases brought by the FBI against researchers, Chinese and American, seeking to steal IP from university labs and from businesses. FBI director Christopher Wray’s “whole of state” threat from China is not hyperbole.

On (2), no one should fault Kirby for addressing the university environment with which he is familiar. But most schools, faculty, and students are not in that top 5% internationally. We know the myriad stories of cheating and plagiarism in schools in China, and students who come to the US with the same attitudes toward doing the work. I’ve seen myself how lack of respect for honest work tends to bring down the performance of an entire class, including that of domestic students. We know the Yale-Peking University program was cancelled in 2012, partly attributable to allegations of widespread plagiarism and cheating.

Dishonesty in academic work is not unknown among American students. But I know of many instances in which faculty at schools in China simply turn their backs on cheating in exams. And they get little administration support when they try to restrain the dishonest behavior.

We know cheating on the college entrance exam – the gaokao – is controlled more now than a decade ago, when attempts to control cheating resulted in an angry mob of 2000 parents yelling at test administrators. “We want fairness. It’s not fair if you won’t let us cheat.”

The national push in China to control cheating resulted in some odd experiments. At our school in Hangzhou the new president decided to promote an honor code in final exams, as is the case at nearby Zhejiang University (Zheda), one of those top schools in China. This is not to take anything away from Zheda. There is an honors option in the Global Engagement Program, designed to cultivate Chinese students for work in international organizations. The program is conducted in English. Professor Kirby would be happy to engage with these students, some of the best and brightest in China.

But at our provincial-level school an exam honor code was DOA among both students and faculty – no one thought it could work. The only faculty member who could give voice or pen to objection, though, was me. Everyone else had careers on the line. I didn’t have to care. But what the president wanted, the president got.

Before the honor code was to be implemented, I did my own experiment. In one economics course I had plenty of scores from homework, quizzes, and a midterm to provide final grades. I had noticed years before that a final exam with a significant weight – 30% or 50% of a final grade – almost never changed a grade from that going into the final exam.

In class we had some discussion of the honor code. I proposed an experiment. The final exam would only count 10% of the final grade. But I would hand out the exams and leave the room for two hours and we would see what result. No monitors in the room. If students cheated, others were supposed to report them to the instructor for consideration, as the university president proposed.

I also arranged with six of my very good students, three foreigners and three Chinese, to take the final exam a day earlier and then take it again during the whole class exam. In the whole class exam they were to very obviously cheat in any way they wished, but so that other students could see. Open textbooks, read from notes, use phones, copy from other students. Make it obvious. And oh, yes – the whole class exam was different from the one I gave my star students.

You can guess the result – my good students cheated as best they could, and no one reported them to me. When my six finished the exam, they hung around outside the exam room and took pictures of students getting up from desks to look at other exam papers and using phones with abandon.

I don’t know if you call the experiment a success or a failure. But no one told me I had to use the honor code in subsequent semesters.

There is little sense of honor built in to these students. Lots of American students are no different. But an honor code needs good intentions. What good intentions do exist can get waylaid by pressures from family, culture, and particularly CCP.

Kirby is impressed by the earnestness, even in the current days of trauma and contestation, with which Chinese academics pursue joint arrangements with American schools. On one hand, that is understandable. Chinese academics are desirous of contacts for academic and personal reasons (including the ability to publish in western journals and to get their own kids into American schools). Kirby alludes to the CCP corporate overlords that can work to encourage or discourage such arrangements. For a few years before 2012, university joint ventures of all kinds were the rage. CCP pushed for engagements and wanted measurable results. A couple of my Chinese government students from Chicago were responsible for those foreign outreach programs. The pressure to get some agreement was palpable – one-way semester exchange, two-way, with or without American faculty in China, some sort of joint program, and even in some cases a joint degree with an American school. My school had a joint civil engineering degree program with San Francisco State University. A couple of years in China and then to the US for the last two or three years. The American degree was worth something. The Chinese degree – not so much. Until recently there was no international accreditation for most Chinese engineering degrees.

We need the Chinese students, undergrad and PhD candidates, for our own development. But we should not lose sight of the ill-preparedness and ill will that still lurks.

Plenty of Chinese, students and families, come to the US for education and business and – dare I say it – the freedoms that accompany a green card. There are tens of thousands of Chinese immigrants to the US each year – 150,000 in 2018. I know several student immigrants personally- come for the advanced degree, stay for the high-paying job. Quite often, their parents tell them not to come back to live, but to stay in America.

Not so many Americans go the other way.

Kirby is right to promote engagement for the good of American schools and students and faculty. Some Chinese universities may well join the upper ranks of international schools in the next ten years. But I hope he – and other administrators and scholars – can go into the engagements with a bit of the skepticism and hard evidence-seeking that led to dismissal of Confucius Institutes at the University of Chicago, Penn State, William and Mary, SUNY, Oklahoma, Texas A & M and others and cancellation of the Yale-Peking U program and consideration of the continual warnings of Chinese deception and theft from attorneys experienced in Chinese business arrangements. Harris Bricken is a good example.

We can take a hint from Ronald Reagan’s treaty policy with the Soviet Union – trust but verify. The expensive dinners and gifts and warm smiles are enticing. Its easy to become enamoured under the influence the velvet-gloved fist. I keep thinking of Sergeant Phil Esterhaus’ warning to street cops before going out on patrol in Hill Street Blues –“Let’s be careful out there.” It can be hard to do that, especially after the wining and dining and graciousness of their potential partners. But Kumbaya this ain’t.

I don’t have hard recommendations for administrators of great American universities. But they should jealously guard the reason they became great in the first place – freedoms of expression, dissent, and honesty in relationships. Too often we have let the Chinese camel’s nose into the academic tent to the detriment of American academic quality standards, research and innovation. A little caveat emptor is always a good idea.